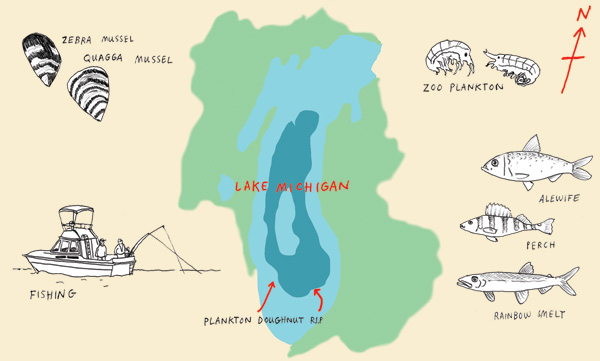

Lake Michigan fish are feeling the squeeze. Predators are too numerous, and there’s not enough food. The results of an annual survey of fish communities in Lake Michigan at the end of 2015 show just how bad things are in the lake: prey fish (including bloater, rainbow smelt, alewife, and other species) were at a record low, down 73 percent from 2012. The culprits? Invasive mussels removing too much food from the system and too many predators feasting on top. It doesn’t look like the fish will rebound anytime soon.

“Based on being out there [in 2015], the trend is continuing,” said Bo Bunnell, a research fishery biologist at the USGS Great Lakes Science Center. “It puts us in a very precarious position of balancing predation by salmon and trout versus enough sustainable prey. We’re teetering at the tipping point.”

Phytoplankton, Zooplankton and Diporeia

Phtyoplankton are the main source of food for zooplankton and small crustaceans like Diporeia, a shrimp-like organism. But mussels have halved the phytoplankton population and destroyed their once-annual spring “doughnut” formation, meaning there’s less for zooplankton and Diporeia to eat. Once, there were 5,200 Diporeia per square meter of water. That number is down to 82.

Invasive Mussels

Zebra and quagga mussels were carried from Europe to the Great Lakes in ships’ ballast water. In Lake Michigan, 35,000 mussels can cram onto one square meter. They’ve carpeted the floor of the lake, encrusted propellers, and clogged industrial pipes, costing the region $500 million per year.

Bloater, Alewife, Rainbow Smelt and Others

As plankton populations crash, the fish that eat them go hungry. So far this has been managed by limiting how much fishermen can catch.

Salmon and Trout

Top lake predators are decimating populations of smaller fish, and they might soon run out of food. If that happens, it could severely impact the $7 billion-per-year Great Lakes recreational fishing industry.