Custer, Camp, and Chicago

|

HISTORY The Windy City is 1,200 miles from Montana’s Little Bighorn River—so what’s its role in the story of the 7th Cavalry’s Last Stand?

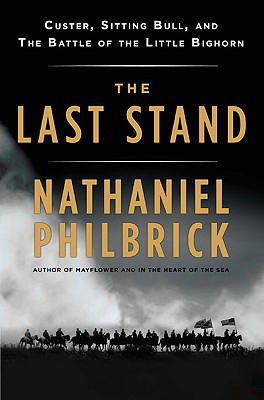

Having spent some time with the Pilgrims (Mayflower) and 19th-century whalers (the National Book Award–winning In the Heart of the Sea), Nathaniel Philbrick now turns his gaze inland toward The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Philbrick tells this often told tale well, his virtues as a storyteller and historian ably backed by 18 excellent maps, nearly 100 pages of dense but lively notes, and a splendid bibliography. Yet after all that, exactly what happened to General George A. Custer and his command remains nearly as great a puzzle as it was 134 years ago.

Surprisingly, Chicago, far removed from the battle scene, played a central role in shaping our perceptions of that deadly encounter between Custer’s 7th Cavalry and a prodigious coalition of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors. First, it’s important to remember that Custer divided his command on the morning of June 25, 1876. Only the three companies—about 220 men—with Custer were wiped out; with Major Marcus Reno in command, the regiment’s other companies withstood a grueling 36-hour siege before other soldiers came to their aid.

In the aftermath of the battle, the country, in the midst of its centennial celebration, went looking for a scapegoat, and Reno emerged as the most likely candidate—particularly once stories began circulating that painted him (not unjustly, in Philbrick’s account) as both a coward and a drunk. Angered by these rumors, Reno demanded a court of inquiry to clear his name. A military court convened at Chicago’s Palmer House on January 13, 1879, and for four weeks it heard from dozens of witnesses, most of them survivors of the battle. “In the end,” writes Philbrick, “the judges refused to condemn Reno, but they also refused to exonerate him”—but the reams of testimony gathered in Chicago remain one of the principal sources about the demise of Custer and his command.

Supplementing that testimony was information gathered by Walter Mason Camp, a civil engineer who in the 1890s began editing a railroad trade journal based in Chicago. Obsessed by the battle of the Little Big Horn, and frustrated, as he put it, by the “tangle of fiction, fancy, fact, and feeling” that surrounded it, he “formed an ambition to establish the truth.” Camp visited the battlefield ten times and interviewed more than 200 survivors and eyewitnesses of the battle, most of them Lakota and Cheyenne. He also collected official documents related to Custer’s final campaign, as well as contemporary newspaper and magazine accounts. A scrupulous researcher who in the end recognized that not every question could be satisfactorily answered, Camp died unexpectedly in 1925, only 58 years old. He never published the book about Custer he had long planned, but, writes Philbrick, “the evidence he collected is voluminous”—and, he might have added, invaluable.

GOOD, RELATED LINKS

- The New York Times review by Michiko Kakutani: “It’s not clear why Nathaniel Philbrick decided that the world needed another book on Custer. [H]e’s turned up little that’s substantially new about Custer, and readable as his book is, it lacks the visceral resonance of [Evan] Connell’s masterpiece,” Son of the Morning Star.

- The Sunday New York Times review by Bruce Barcott: “By all rights [Custer] should be a footnote. That he enjoys the glory of single-name recognition is a testament to the power of personality, show business and savvy public relations. Custer wasn’t just an Indian fighter. He was one of the first self-made American celebrities.”

- Celia McGee, at the Chicago Tribune’s “Printers Row” blog, wrote: “The book’s most lasting impression is of immediacy, strangeness, danger and doom, which Philbrick brings out in every rock, cloud, blade of grass and mountain range. It reminds us that dying, in whatever cause, is never expected by those it happens to, and that wrong decisions to go to war didn’t always commence with the flip of a cell phone.”

- The entire testimony of the Reno Court of Inquiry is available online. But as Philbrick and others have noted, some officers may have fudged their testimony so as to protect Reno. “Perhaps the most useful account” of the court’s inquiry, says Philbrick, is that compiled by the Chicago Times, since it “contains testimony and context that never made it into the official transcript.” Be forewarned: the modern-day edition edited by Robert Utley can be tough (and pricey) to acquire.

- Kenneth Hammer has gathered Walter Camp’s notes into a book, Custer in ’76, that is prefaced by a short biographical sketch of Camp.

- One easy way to gauge the shift in perceptions about Custer is by looking at two movies: They Died with Their Boots On (1941)—with Errol Flynn and his frequent costar Olivia de Havilland in their last film together—depicts Custer as, in Philbrick’s words, a “noble hero,” while 29 years later, the gorgeous, funny, and tragic Little Big Man would render him as a “deranged maniac.” Richard Mulligan portrays Custer; Dustin Hoffman is marvelous in the title role.