Yesterday Carol Marin broke the story that ex-Mayor Daley could be added to a civil lawsuit resulting from the Burge case—filed by Michael Tillman, who spent 23 years in prison for a murder he’s since been exonerated of—and that he’s scheduled to be deposed on September 8th.

It wouldn’t be the first time Daley has had to answer questions about Burge; he was sat down by a special prosecutor in 2006 to answer questions about his role in the scandal as state’s attorney (for which he has prosecutorial immunity). But the interview was considered by many to have been useless:

At a news conference in the lobby of the Dirksen U.S. Courthouse, [Flint] Taylor highlighted how Daley, in the interview, acknowledged that he must have received a critical 1982 letter from a Cook County Jail doctor about the alleged torture of Andrew Wilson, a suspect in the murders of two Chicago police officers.

The transcript, however, shows that city Corporation Counsel Mara Georges interrupted the mayor’s answer, telling him, "Just if you remember."

"I don’t remember today," Daley then said.

[snip]

Daley said he couldn’t recall in answer to more than 20 questions during the interview.

The transcript shows sometimes long and rambling questions or comments by Egan and his deputy, Robert Boyle, followed by usually brief responses from Daley.

Noting that Wilson was in such bad shape–apparently after being beaten by police–that officers at the lockup would not let him in, Boyle posed his question this way: "I assume that nobody ever brought that to your attention?"

"No," Daley answered.

Or as John Conroy put it in the Reader:

Egan and Boyle are former high-ranking attorneys in the state’s attorney’s office, and their enthusiasm for investigating Daley’s role might best be illustrated by the fact that they didn’t interview him under oath until June 12, 2006, when their report was virtually complete. They asked him about office procedures, personnel assignments, and only one of the more than 50 cases that occurred on his watch, the infamous Andrew Wilson case.

In Conroy’s article, "Twenty Questions," he predicted that Daley was most likely to see questioning again as a result of a civil lawsuit, which is looking like the case. Though as Marin notes, Daley’s lawyers filed a motion on August 5th for reconsideration involving the former mayor’s inclusion in the civil suit. They focus on the basis that his actions as mayor—for which he’s not immune—do not rise to the level of conspiracy or unlawful suppression.

IANAL, but Daley may have reason for confidence. Even though Judge Pallmeyer’s ruling keeps the door open, it doesn’t leave it wide open. For instance, here’s how Pallmeyer granted Daley’s motion to dismiss the first count (deprivation of fair trial, wrongful conviction):

Much of Daley’s argument rests on assertions that his involvement with the suppression of this information was at a supervisory level, or that he was not personally involved in its suppression, or that its suppression sprang from his role as a prosecutor, rendering him immune from any liability. The allegation Plaintiff makes, however, is that Daley, as Mayor, personally acted to suppress evidence of torture at Area 2, and to undermine the value of any such information that did

become public.

That said, the court observes that the evidence allegedly suppressed by Daley does not appear to be the type of material exculpatory evidence that Brady addresses. Plaintiff alleges that Daley was on notice of torture at Area 2 by virtue of public hearings and in an Amnesty International report. But that information was not “suppressed”—the hearings and the report were public. (Compl. ¶ 85.) Daley’s alleged public statements discrediting the Goldston Report does not constitute suppression, nor is there any allegation that he personally withheld the report between the time of its creation and 1992 release. (Id. ¶¶ 76-83.) Refusing to launch investigations, and, indeed, promoting Dignan, are also not fairly characterized as suppression…. While there is a blanket allegation that “Defendant Daley did not disclose exculpatory information in his possession,” (id. ¶ 74), Plaintiff fails to allege with any specificity what that information might have been, whether it differed from information that had already trickled out into the public, or whether Daley took specific steps to conceal that information.

[snip]

Had Daley been in possession of undisclosed information that Burge and his subordinates had engaged in other instances of torture at Area 2, such information could be material and exculpatory even if it did not relate directly to Plaintiff. The conduct of Mayor Daley that Plaintiff challenges in this case does not relate to such undisclosed information, however, and

did not otherwise influence Plaintiff’s conviction and sentence.

The central part of the news stories about Pallmeyer’s ruling focused on the fact that Pallmeyer didn’t grant Daley’s motion to dismiss in the conspiracy counts. But that opening is just a crack (emphasis mine):

[T]he Defendant Officers are alleged to have participated directly in the torture, as did Burge; Frenzer allegedly did so as well, by attempting to take a statement when he knew the torture was ongoing; Martin and Daley are said to have undermined and obstructed findings of torture; Shines allegedly suppressed findings of torture; and Plaintiff claims that Needham and Hillard continued to suppress findings and undermine investigations into torture at Area 2 after they took office…. These allegations are sufficient to allege a § 1983 conspiracy. More specific allegations against the individual Defendants–a showing that their decisions to join in the general purpose of the conspiracy were deliberate and coordinated, for example–would indeed be helpful. The nature of conspiracy itself often prohibits such detail at the pleading stage, however. The court concludes Plaintiff has presented more than “naked assertions,” and his conspiracy claim survives.

Obviously Daley being deposed would be a big deal, no matter what happens—but his exposure in the lawsuit, as a defendant, seems small.

Related: The excerpts from Pallmeyer’s opinion use a lot of names and terms that may be unfamiliar; the best place to start, if you want to catch up on the details of the less famous players, is Conroy’s 2006 who’s-who, which covers Dignan, Shines, Martin, and others.

Update: Carol Marin discusses the case on Chicago Tonight:

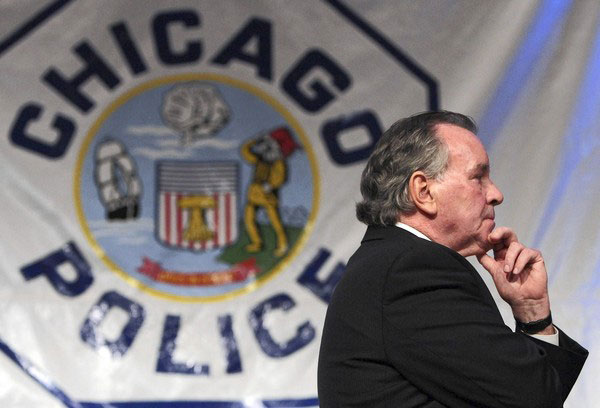

Photograph: Chicago Tribune