Tonight at Millennium Park at 6:30, the outstanding local new-music ensemble Eighth Blackbird plays Steve Reich’s Double Sextet, the Pulitzer-winning piece they commissioned from the veteran minimalist composer, along with his classic Music for 18 Musicians. The complaint about minimalism is that it can sound a bit samey, so this pairing of works should provide a good comparison across Reich’s career and contrast across his compositional styles.

Reich likes to make rhythmic music of considerable density, and Eighth Blackbird is a small ensemble that was almost too small for Reich, to the extent that he almost didn’t take their commission:

I said, "Gee, I’ve heard of them—what’s their instrumentation?" She replied, "Well, one flute, one clarinet, one violin, one cello, piano, percussion." I said, "Jenny, I can’t write for that." Pierrot plus percussion, we call that.

[snip]

For me, instrumentation is inspiration, because I invent my ensembles. I’m not writing for a string quartet, I’m writing for three string quartets. I’m not writing for Pierrot plus percussion, I’m writing for this double sextet. So getting the instruments right is really what gets me going.

Reich’s solution was to have the ensemble play against a recording of itself, but the piece is still more open and airy than much of his earlier work. The second movement in particular, II. Slow 6:43, is an eerie, fragile, almost ambient sound that relies heavily on unnerving woodwinds.

It’s a warm, analog piece in comparison to the 35-year-old Music for 18 Musicians which, despite being written for acoustic instruments, has always felt digital to me, thanks to its pulsating rhythms. Reich explains how it works in his notes to the score:

Rhythmically, there are two basically different kinds of time occurring simultaneously in Music for 18 Musicians. The first is that of a regular rhythmic pulse in the pianos and mallet instruments that continues throughout the piece. The second is the rhythm of the human breath in the voices and wind instruments. The entire opening and closing sections plus part of all sections in between contain pulses by the voice and winds. They take a full breath and sing or play pulses of particular notes for as long as their breath will comfortably sustain them. The breath is the measure of the duration of their pulsing. This combination of one breath after another gradually washing up like waves against the constant rhythm of the pianos and mallet instruments is something I have not heard before and would like to investigate further.

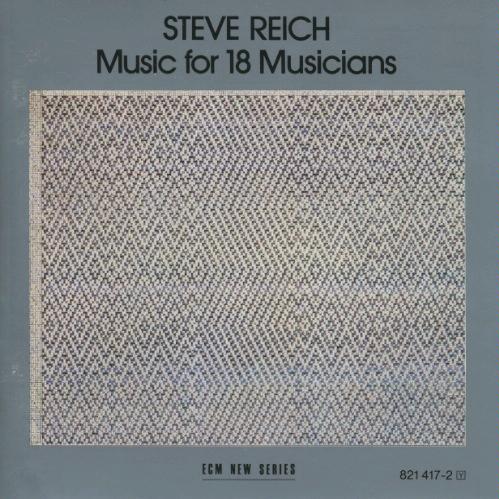

Music for 18 Musicians was the first "new music" piece I ever heard. I was initially attracted by the cover, which looked like a dot-matrix blanket. Turns out I wasn’t far off:

“Just as the spinning and gathering of wool serve as the raw material for a weave, so the artist working with video selects images to serve as the basic substance of the work.” For most of the 1980s, Korot concentrated on a series of paintings that were based on a language she created that was an analogue to the Latin alphabet. Drawing on her earlier interest in weaving and video as related technologies, she made most of these paintings on hand-woven and traditional linen canvas.

I came to Reich’s piece in the early days of the Web, when I was still figuring out computers, and it will always represent that time for me, when I was learning how the digital world emerged out of and fed back into the real world. What instrumental music "means" is a tricky and often dumb question, hence the old saw of "dancing about architecture," but Music for 18 Musicians sounded to me like that world being created. If you’ve seen Terrence Malick’s The New World, you might remember the opening, in which John Smith discovers the "new world" to the layered strains of the prelude to Das Rheingold:

That’s what Music for 18 Musicians brings forth inside my head, only the new world was a virtual one.

I was living in rural Virginia at the time, and it also sounded like the city, or what the internal life of the city might sound like as converted to music. Think of the chooga-chooga beat behind Johnny Cash’s train songs and so much other country and rockabilly, and how that emerges out of the landscape, and imagine that coming out of the city. As Alex Ross wrote of Reich in The Rest Is Noise:

He reacts swiftly to slight sounds in his midst—the soft buzz of a cell phone, a siren on the street outside, the whistle of a teakettle. Each sound contains information. The 1995 work City Life conveys what it would be like to experience the world through Reich’s ears: the hidden melodies of overheard conversations and the rhythms of pile drivers melt together into a smoothly flowing five-movement composition, a digital symphony of the street.

City Life, with car horns, closing doors, and hissing steam sneaking out between the percussive music, sounds more like an actual city, but I hadn’t lived in one then, and my abstract conception of it, a grid of information as much as streets and tracks and wires, was Music for 18 Musicians.

I flash back to Reich’s music whenever I’m at Union Station waiting for the Metra, where the track location announcements, meant to aid the blind, overlap in a minimalist cacophony: almost like the city paying tribute back to Reich and his contemporaries.