Readers of Dickens will probably recall that, during Victorian England, the wealthy took a voyeuristic interest in the lives of the poor, which eventually mutated into actual poverty tourism and spread to the United States. As the New York Times wrote in 1884:

"Slumming," the latest fashionable idiosyncrasy in London—i.e. the visiting of the slums of the great city by parties of ladies and gentlemen for sightseeing—is mildly practiced here by our foreign visitors by a tour of the Bowery, winding up with a visit to an opium joint or Harry Hill’s…. It is safe to conclude under the circumstances that "slumming" will become a form of fashionable dissipation this Winter among our belles, as our foreign cousins will always be ready to lead the way.

Around the time of the Columbian Exposition, Rand McNally found it so necessary to ensure poverty tourists were entertained that it devoted better advice for getting around among the other half than it did to restaurants and museums, even if our offerings of human suffering were scanty compared to the veritable Disneyland of squalor on offer in the Old World:

A celebrated European philanthropist, who recently visited Chicago, is recorded as saying that the prevalent dirt and flagrant vice there visible exceeded everything in London, but that he had seen scarce any evidence of actual want.

Chicago of a night-time is another city to Chicago by day. The business and family portion of the community being mainly housed in comparative comfort or superlative splendor in the outskirts, it is to the pleasure-seekers, and alas! in certain less reputable quarters, to their parasites, that our streets are given over on an evening.

[snip]

Some suggestions as to a good route for a nocturnal ramble, and the sort of things a person may expect to see, may be useful. If you are in search of evil, in order to take part in it, don’t look here for guidance. This book merely proposes to give some hints as to how the dark, crowded, hard-working, and sometimes criminal portions of the city look at night.

Alas! Or, not alas enough:

Slumming.— One of the diversions in London used to be to make up a party, secure the divisions of an experienced police officer—usually a detective—and visit the region of poverty and crime of the East End. That miserable little precinct is called the "slums," and hence the verb. But Chicago has little to show, as yet, which resembles the narrow and intricate streets, the blind alleys, hidden courtyards, and murder-inviting places along the lower Thames and in Whitechapel. "Slumming, therefore, in the London sense of the word, can not be satisfactorily carried out here….

If you really needed the details of what not to do in order to… better avoid the evil or something… Rand McNally was happy to provide:

Opium smoking-rooms, popularly called "joints," are hidden away in Clark Street, but it is dangerous to visit them, as the police are likely to raid them at any moment, and the consequences to every one found there are exceedingly unpleasant. The price of "hitting the pipe" is $1. The habit has spread outside the Chinese quarter, and now "joints" exist uptown, whose patrons are wholly white men and women, who yield themselves to the pipe without any restraint of dignity or decency.

My pick for best opium joint didn’t make it into this year’s Chicago best-of issue, unfortunately.

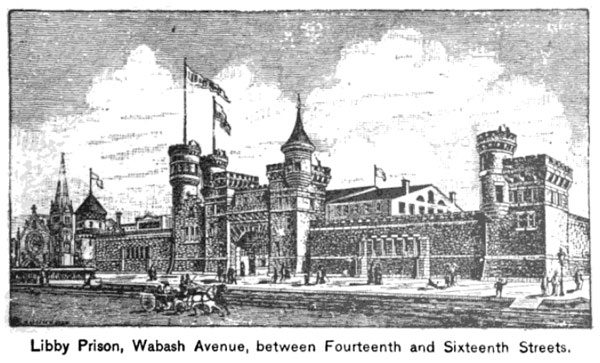

If you were the law-abiding type but still wanted to spend your vacation being reminded of man’s capability for destruction, Chicago still offered plenty of opportunities. The first four listings under "Museums, Etc" were the Libby Prison Museum ("during the war more than 12,000 Union soldiers were confined in it"); John Brown’s Fort ("now enclosed in an elegant building"); The Battle of Gettysburg Panorama ("a realistic picture of this terrible conflict") and the Chicago Fire Panorama ("a vividly realistic representation of the conflagration at its height").

Literalists, on the other hand, might have taken an interest in the Hardy Subterranean Theater, something between a Field Museum exhibit and Epcot Center:

Though the elevator car (a miniature theatrical hall in itself, accommodating comfortably one hundred people) only moves up and down in a shaft about fifteen to twenty feet deep, the illusion is made perfect by a combination of mechanical devices, and the effect produced is a real descent about 1,000 to 1,200 feet under the surface of the earth.

Illustration: Rand, McNally & Co.’s Handy Guide to Chicago and World’s Columbian Exposition