The Chicago Teachers Union just set its strike date for September 10th if a contract agreement is not reached, with a unanimous vote from the CTU board of delegates. The Tribune reported that a "high-ranking education source" says Brizard is on his way out, though Emanuel denies it. It's a chaotic week, but in Catalyst, Sarah Karp reports some good news from CPS:

Overall, nearly 60 percent of 2011 CPS graduates enrolled in college last fall, up from 56 percent in 2010, according to Clearinghouse data CPS quietly posted on its post-secondary website. Black and Latino males continue to trail other groups, but both saw increases of 5 percentage points.

“It is really good news,” says Eliza Moeller, a lead researcher for the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. She says the college enrollment rate has been flat for a while, going up only 1 or 2 percentage points each year. “It is exciting to see progress.”

Looking at the numbers, the overall gains from 2006-2011 are impressive: in 2006, 48 percent of graduates were enrolled in college; in 2011, 60 percent. The percentage of those students enrolled in two- and four-year colleges stayed the same (66 percent and 34 percent), but the percentage enrolled full-time increased from 68 percent to 77 percent. Karp credits an initiative from Arne Duncan for the change:

Duncan’s team, led by Greg Darnieder, sought, for the first time, to find out how many CPS grads enrolled in college. When the numbers first came in, in 2004, they were shocked: Only 43 percent of grads had made that transition to higher education.

They responded with a number of initiatives. For example: Holding principals accountable for getting each student to fill out financial aid forms and apply to colleges, and giving high schools college coaches to help students choose and follow through. With up to 350 students each, regular counselors had little time for this.

CPS implemented a simple system to check on it, and the numbers went up quickly:

The FAFSA completion rate for seniors was 86.4 percent in 2010, up from 64.5 percent in 2007, said CPS spokeswoman Monique Bond. More than 85 percent of CPS students come from low-income households, she said.

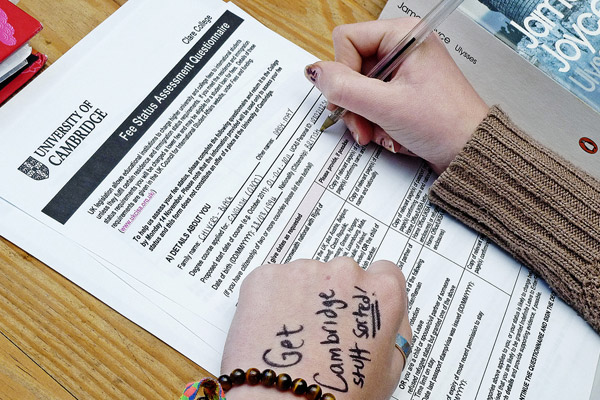

When my wife applied to law school a few years ago, it was not the excruciating process I remember as a kid. The process of being an adult—paying bills, paying taxes, applying for jobs—had conditioned us to being able to track down all the right pieces of paper, reading long gray lists of necessary information, spending hours on the phone in a transfer mobius strip. As a disorganized 17-year-old, even with the help of a parent who was a college teacher, it was awful: not just trying to divine the right place to live and study for four years, but the tendentious process of checking all the boxes. (Coming from a broken home made it more difficult still, as anything involving finances had to be done twice, with me as an uncomfortable relay.) Few people I knew got much official help from their school; it was largely a matter of parents and culture. In that sense, it's a very adult activity, perilously unstructured at a time when everything is structured, and those few months of transition were difficult.

There's plenty of desire out there for it, as the Center for American Progress found in Chicago:

Like their counterparts nationally, Chicago students have high educational aspirations. On a 2005 survey, 83 percent of Chicago seniors stated that they hoped to earn a bachelor’s degree or higher, and an additional 13 percent aspired to attain a two-year or vocational degree. Parents seem to support their children’s aspirations. More than 90 percent of seniors stated that their parents wanted them to attend college in the fall after high school graduation. Latino students, reflecting national trends, were slightly less likely to aspire to complete a four-year degree (with 75 percent aspiring to a four-year degree), and slightly fewer, 87 percent, reported that their parents wanted them to attend college.

So why don't they just go? CAP found that financial aid—the process, not even necessarily the finances—was a surprisingly large impediment:

Students who completed a FAFSA had an 84 percent predicted probability of enrolling in a four-year college versus a 56 percent predicted probability for students who did not complete a FAFSA. This finding may be a proxy for the overall level of norms and supports for college in the school environment. It may also indicate that failure to complete a FAFSA creates a significant barrier to college enrollment for low-income students.

In short, they found that students who could get into four-year colleges didn't try, or tried and stopped in the middle of the process. Which makes some sense; high school is regimented, college is regimented, but the transition between the two really isn't.

Photograph: Stewart Black (CC by 2.0)