Photo: Michael Tercha/Chicago Tribune

Rahm Emanuel testifies on pension reform before the state legislature, May 8, 2012

The New York Times front-paged Chicago's pension problems today. It's a good overview, though it'll be familiar if you've read a lot about it. Between the lines, however, there's stuff of interest:

Chicago’s troubles, experts say, were years in the making. They are the result of city contributions under a state-authorized formula that failed to accumulate nearly enough money, two economic downturns in the 2000s that led to heavy investment losses, and an impasse in the State Capitol despite urgent calls to cut costs of the state’s own pension system. Illinois, which has the most underfunded state pension system in the nation, controls Chicago’s benefit and funding levels.

But not that many years in the making.

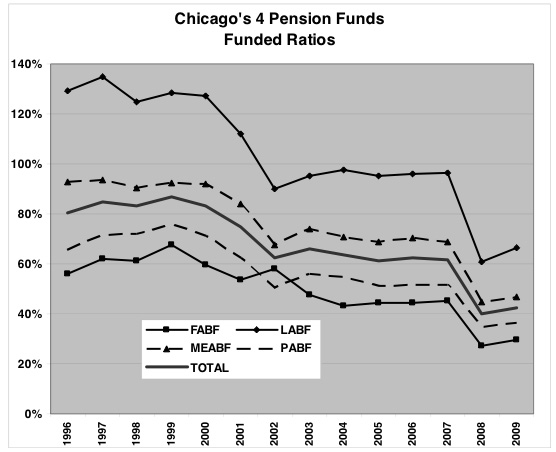

By 2000 you're still around 80 percent funding—a level that makes some pension experts uncomfortable, but it's not bad. What's interesting about this is that the funds never recovered after the dot-com burst and the post-9/11 recession. There's a little, trivial bump from 2002-2003. Even during the next bubble, the city's pension ratios didn't rise.

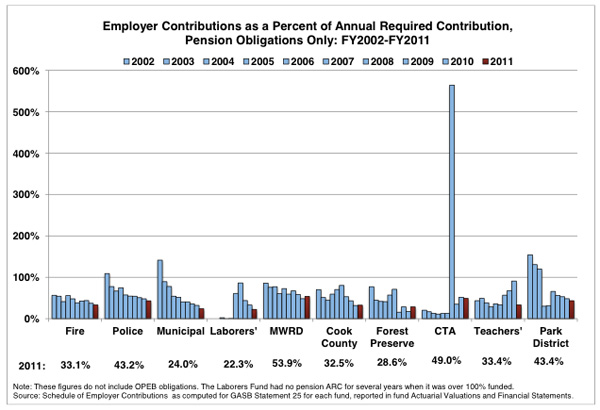

Here's a big reason why.

As the economy improved, from about 2003-2007, the city didn't necessarily increase contributions to pension funds (the huge CTA outlier comes from a bond sale). The Civic Fed estimates that the contribution underfunding shorted the systems by $7.3 billion in those ten years, about 23 percent of total unfunded liabilities, or 29 percent of the unfunded liabilities that should be funded, if you're using 80 percent funding as a baseline.

Another thing happened from the mid-90s to the teachers pension fund, which Eric Zorn spent a couple days trying to figure out. The short answer is that during the mid-90s panic over Chicago's terrible schools, the legislature offered Chicago an appealing deal: divert your property taxes from pensions to schools, and we'll offer you a big cut of the downstate teachers pension fund that Chicagoans pay into.

You can probably guess how that turned out.

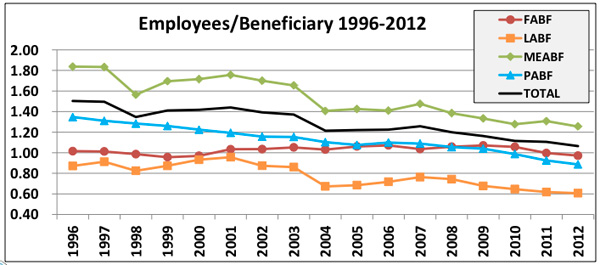

Finally, there's a third big driver of underfunding: what a city financial team, in a presentation at the Chicago Investors Conference, describes as "less people paying in as government restructures."

When workers retire, that's one salary off the books, if that worker isn't replaced. But it's also one new pension and one less pension revenue source. Detroit's ratio was almost 2004. After drastic cutbacks in city services in a shrinking city, it's now 60/40, retirees to workers. In that sense, and in the others, austerity begets itself.