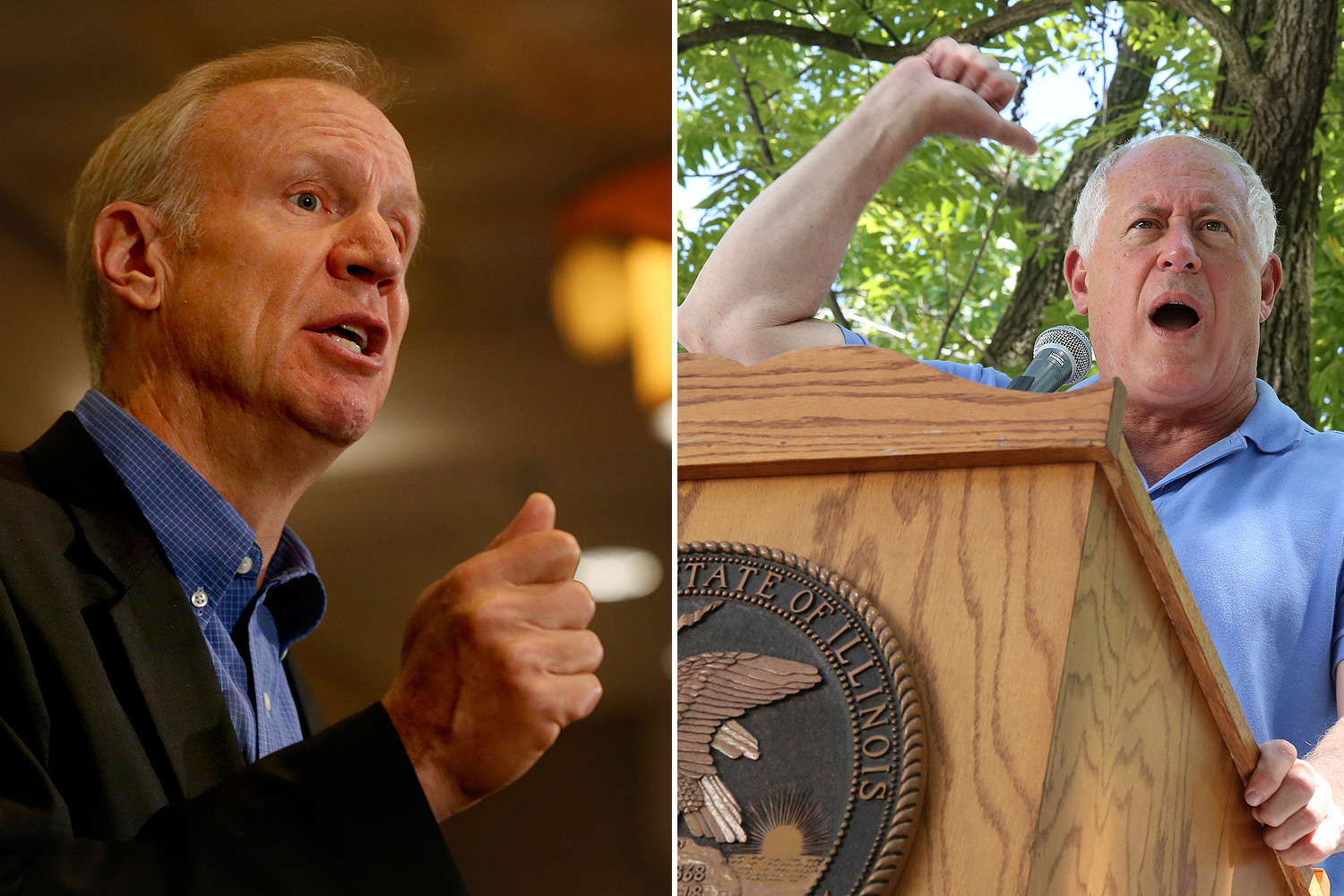

As the campaign heads into the straightaway, Pat Quinn and Bruce Rauner are on day two of talking about infrastructure: yesterday at the Illinois Agricultural Legislative Roundtable downstate, and today at the Chicago-based Metropolitan Planning Council's annual luncheon. Yesterday's session laid out some unanswered questions:

But Rauner did not address how he would provide billions of dollars for annual public works improvements, and a state audit raises questions whether there’s enough money in road fund diversions to fulfill his pledge.

[snip]

Rauner, however, also opened the door to borrowing — the traditional way public works projects are paid for — as well as public-private partnerships for unspecified projects to help pay for new infrastructure and infrastructure repairs.

Today Rauner re-emphasized a willingness to borrow: "we can and should borrow for major new infrastructure projects that have 30-year-plus paybacks," a specifically typical timeframe for infrastructure funding.

Pressed on the state's gas tax, which hasn't been increased since 1990 and has slowly been eaten away by inflation, Rauner said he "wasn't a fan," citing its regressive nature; Quinn, for his part, agreed with Rauner on this.

Where the difference and heat between the two candidates emerged was on a different tax: not for stuff, but for services. The expansion of the state's tax base is critical to Rauner's plan to dial back the income tax increase while fully funding infrastructure and staving off cuts to education, and offered Quinn a line of attack.

"The growth states don't have high income taxes. They have a modernized tax code with a broad base, a low base. We've got to get a handle on our property taxes," Rauner said. "We've got to put a cap on those and stop relying on property taxes so heavily."

Instead, Rauner wants to revamp the sales tax.

"We are one of the few states who only tax products with our sales tax. That's very rare. We've got to modernize our tax code," Rauner said. "We used to be a heavily product-driven, manufacturing-driven economy. Today we're much more of a service economy. We don't tax services. We've got to look creatively at which services, especially business services, that we can and should tax with a sales tax. It's painful, I hate to put new taxes in place, but this is an important, pro-growth, pro-investment policy. We shouldn't tax investment and income, we should tax consumption. That's the pro-growth approach to it."

This idea has been floating around for awhile. Back in 2011, the state's Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, ran the numbers on new revenue service taxes would create. They first found that the Illinois economy is particularly service-dependent within the region, and its proportion of the economy grew from 32 percent of the state economy in 1977 to 48.5 percent in 2009. Hawaii lead with 160 taxed services; the average state taxed 56; Illinois taxed, at the time, 17. So as the economy turned to the service industry, taxes didn't, reducing consumer-driven revenues.

Illinois has a few service taxes, which you're probably familiar with: electricity, natural gas, amusement, hotel, auto rental, and so forth. So even though they're services, a number of those service taxes go to necessities.

Once you open up a much broader range of services to taxation, there's all sorts of stuff to tax. COGFA lists, among many other things: pet care, landscaping and lawn care, mini-storage, barber shops, funeral services, portrait studios, temp services, golf-club memberships, pest control, tire retreading, and so on.

Some of these would be huge revenue streams, like taxing attorneys, which five states do. Some would be comparatively piddling, like armored car services, which 16 states tax. Overall, COGFA estimated that the full menu they presented would bring in $8.5 billion; subtracting business-to-business taxes would result in four billion in new revenue, offsetting Rauner's plan to step back the income-tax hike.

It's an idea that's gotten support, as from Crain's Joe Cahill, working off an Illinois financial-health SOS co-authored by the legendary Fed chair Paul Volcker. But it'll bring expected opposition; when Emanuel got behind the idea a couple years ago, the National Federation of Independent Businesses fought back against the "Rahm tax."

Quinn stuck to his guns on the sales-tax expansion, zeroing in on Rauner's statement that we "shouldn't tax investment and income" and launching into a populist reading of the plan.

"I am not for taxing consumption. I heard that somebody said that earlier today. That's just plain wrong. It shifts the tax burden onto ordinary people, everyday people who live from paycheck to paycheck," Quinn said. "I fought my whole life for a fair tax system based on ability to pay. I think that's a principle as old as the Bible."

After the forum, Quinn brought it back to Rauner's answers, and his wealth.

"For some billionaire, who has all this income, $53 million in just one year, to say that we should have more consumption taxes on ordinary people, and lighten the load on investment income of billionaires, that won't pay the bills," Quinn said.

There's space in between there. According to COGFA's 2011 estimates, two of the three biggest sources of their projected service-tax revenues would be attorneys and investment counseling, and there are smaller, more populist-friendly targets like chartered flights, executive-search services, and interior design. But until that happens, a significant battle line has been drawn for the election.