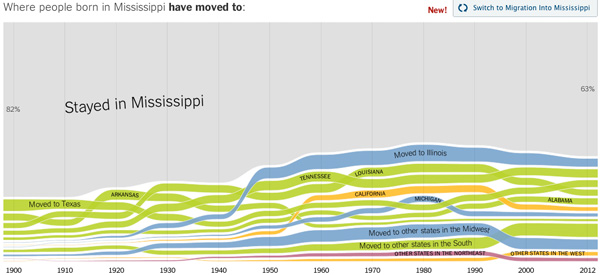

Not long ago the New York Times published a great data visualization showing where which states the residents of each state were born in, throughout the course of the 20th and early 21st century. Illinois's results are not especially revealing: California and Florida are the two main destinations. The South is close to the rest of the Midwest as a destination (it's surpassed it, if you include Florida), which may be a mild surprise, but the increasing draw of the South, once it finally modernized, isn't much of a secret.

The most interesting data about Illinois isn't in the Illinois report at all. It's this:

That's actually pretty interesting. For the most part, the out-migration patterns for states are heavy on California and Florida and whatever the neighboring states happen to be. Migration tends to point west and south in the 20th century, because the West and the South came around a bit late. As part of the series, the Times noted this.

So Illinois dominating the Mississippi diaspora is unusual. But the reason is relatively simple: the Illinois Central Railroad. Here's what it looked like in 1895:

Like the Mississippi River running in reverse, the Illinois Central ran tributaries throughout Mississippi, which then spread out into a delta as it approached Chicago. The city is very southern, as a result of the Great Migration, but even within that context it's very Mississippean. And those ties persisted for decades after the train ceased to be the man vehicle of migration as those ties were strengthened.

I've written about this before. But I was curious: what about Iowa? The Illinois Central ran the length of three states: Mississippi, from which there was a huge migration; Illinois, where those travellers went; and Iowa.

I hadn't really thought about Iowa (sorry, Iowa; I know that's kind of what happens). But then I remembered this:

It's difficult to know exactly how many of Iowa City's residents are actually from Chicago and to know who is moving where, when, and for how long – even the new Census population estimates out this week, confirming the reverse of the suburban exodus, can't tell us. But Iowa Citians have traditionally turned to local affordable housing data to measure how many Chicagoans have moved to Iowa City. As the Tribune reported, in 2007, 14% of those using the program in Iowa City were from Illinois, "most from Chicago".

It's starting to get some attention. The Tribune's Barbara Brotman published a long piece this year on Iowa transplants to Chicago. It's the subject of a 2010 film, Black American Gothic, and a 2014 book, A Transplanted Chicago. A 2010 study out of the University of Michigan's Population Center noted that gentrification and the disappearance of public housing was pushing residents out—and while the "reverse Great Migration" has received a lot of attention, Chicagoans have been moving in smaller numbers to Iowa, though they carry the burden of the city there:

The stigmatization of Chicago migrants plays a profound role in shaping social relationships, both among fellow migrants and between Chicago migrants and Iowans. Several participants describe how Chicago is often blamed for “everything that goes wrong in Iowa City,” particularly in relation to drugs and crime. According to 53-year-old Diane Field, “It's just, Chicago, Chicago, Chicago. I mean, everywhere you go they talk about us. There were drugs in Iowa long before anyone came from Chicago.”

For some residents, Iowa is a fresh start—but it's one following old paths.