There is also the need for an apocalyptic scenario that is specific to "Western" society, and perhaps even more so than the United States. (America, as someone has said, is a nation with the soul of a church—an evangelical church prone to announcing radical endings and brand-new beginnings.) The taste for worst-case scenarios reflects the need to master fear of what is felt to be uncontrollable. It also expresses an imaginative complicity with disaster. The sense of cultural distress or failure gives rise to the desire for a clean sweep, a tabula rasa. No one wants a plague, of course. But, yes, it would be a chance to begin again. And beginning again—that is very modern, very American, too.

—Susan Sontag, AIDS and Its Metaphors

The life of writing about policy, truth be told, is not a romantic one. Consider the existence of someone tasked to write about, say, pensions in Illinois or Chicago. Many of those funds have seemingly been teetering on the brink for longer than the lifetimes of the people analyzing them, without any kind of dramatic reckoning. It is, as Susan Sontag writes of so many other things, "a long-running serial: not 'Apocalypse Now' but 'Apocalypse from Now On.' Apocalypse has become an event that is happening and not happening."

So much of the process, as is the point of her book, is metaphor creation. What will shock the system? (I know, maybe an animated python will do it.)

The temptation to break the glass and pull the fire alarm, in this scenario, is strong. And that is how, I think, the Tribune's Kristen McQueary ended up with the entire Internet mad at her all this past weekend.

The editorial board member published an essay entitled "In Chicago, Wishing for a Hurricane Katrina." (That's the original, preserved by the Huffington Post's Kim Bellware; it was quietly revised shortly after online publication.) It begins as follows.

Envy isn't a rational response to the upcoming 10-year anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

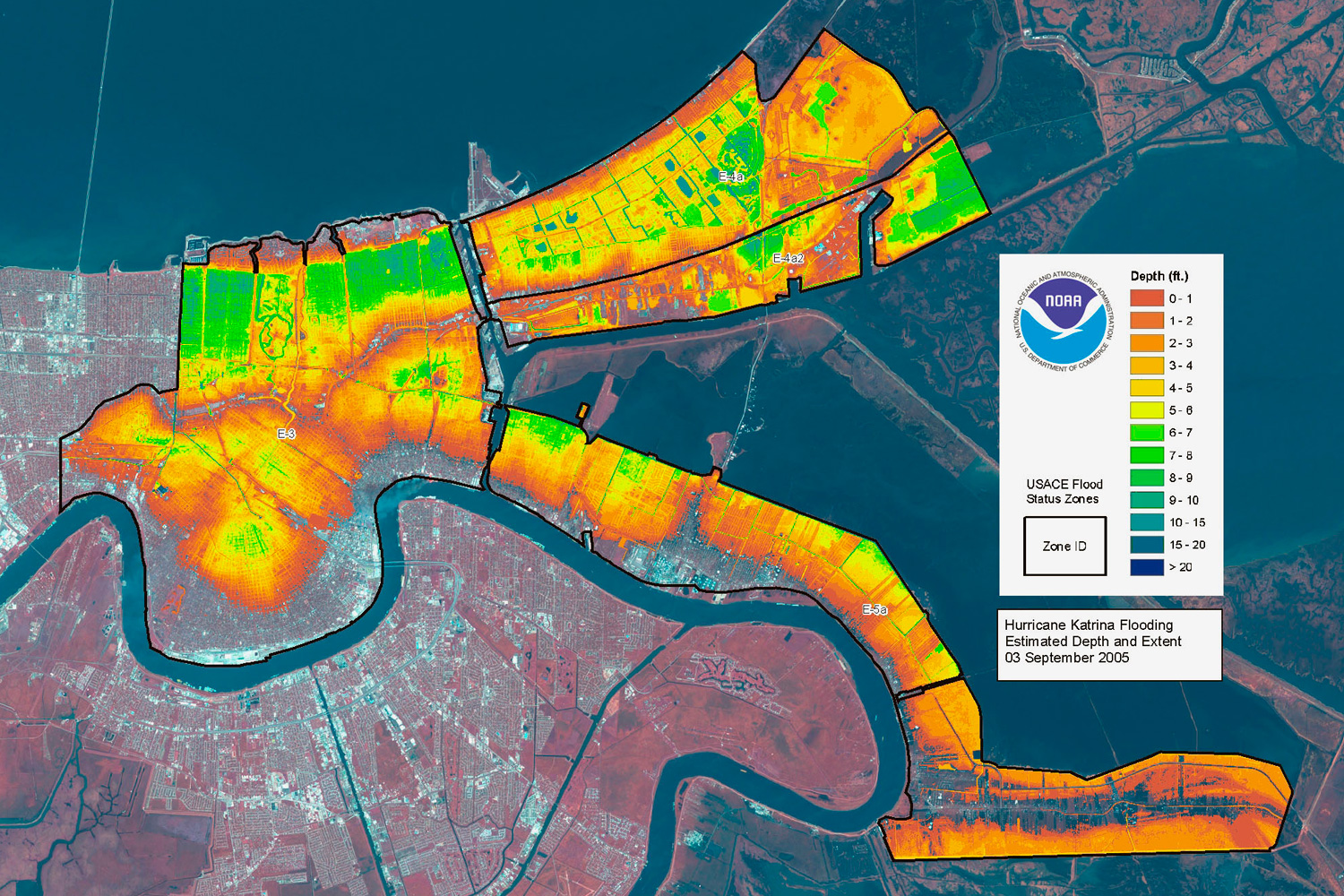

But with Aug. 29 fast approaching and New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu making media rounds, including at the Tribune Editorial Board, I find myself wishing for a storm in Chicago—an unpredictable, haughty [Ed. note: haughty?], devastating swirl of fury. A dramatic levee break. Geysers bursting through manhole covers. A sleeping city, forced onto the rooftops.

It concludes, referring to "middle-class taxpayers":

That's why I find myself praying for a real storm. It's why I can relate, metaphorically, to the residents of New Orleans climbing onto their rooftops and begging for help and waving their arms and lurching toward rescue helicopters.

Except here, no one responds to the SOS messages painted boldly in the sky. Instead, they double down on their own man-made disaster.

This was revised to begin: That's why I find myself praying for a storm. OK, a figurative storm. OK—he said with affected casualness—then.

My former colleague Michael Miner argues that McQueary never meant that the "storm" was supposed to be a literal natural disaster that killed almost 2,000 people and displaced the city overnight, and that reasonable people should have assumed this. McQueary has said as much, and I have no reason to doubt it.

But it is worth considering how obvious Katrina as metaphor, not desire, was supposed to sound. Arne Duncan said that "the best thing to happen to the education system in New Orleans was Hurricane Katrina." A representative from Baton Rouge said "We finally cleaned up public housing in New Orleans. We couldn't do it, but God did." The New York Times's Bob Herbert writes of this period:

During the immediate post-Katrina period, there were essentially two visions of a resurgent New Orleans. One, widely decried as racist, saw the new, improved New Orleans as smaller, whiter and more prosperous.

This was openly advocated. Just a few days after the storm, a wealthy member of the city’s power elite, James Reiss, told The Wall Street Journal: “Those who want to see this city rebuilt want to see it done in a completely different way: demographically, geographically and politically.”

Mr. Reiss, who is white and served in Mayor C. Ray Nagin’s administration as chairman of the Regional Transit Authority (he has since left the government), said that he and many of his colleagues would leave town if New Orleans did not become a city with better services and fewer poor people.

Or as former Chicago journalist Gary Rivlin, author of the definitive book on Harold Washington, reports in his new book, Katrina: After the Flood:

[Rivlin] examines the specter of a “Katrina cleansing” — fears that the city’s business elite were conspiring to repossess property and re-establish a white majority electorate. Lance Hill, a white political activist serving as a mole, tells Rivlin: “It was impossible not to pick up on this sentiment that this was our chance to take back control of the city. There was virtually a near consensus among whites that authorities should not do anything to make it easy for poor African-Americans to come back.”

Many have not forgotten how perilous the line between metaphor and desire was in the immediate wake of the storm; any use of Katrina as metaphor must be grounded in that history.

The worst scenarios of New Orleans's rebirth did not come to pass, though it did lead to the astonishing blood-relative zoning in St. Bernard Parish, and as Rivlin points out, the opportunity was used to abandon Charity Hospital and fire all of the city's teachers—the latter an outcome Sarah Carr describes in Hope Against Hope as "an attack on the city's black middle class, even if not intended as such." Still, the rebirth has been more difficult than McQueary's editorial, with its narrow focus on policy, would imply. The median household income for whites and Latinos in New Orleans defied national trends from 1999 to 2013, barely falling; the median income for blacks fell at close to national rates over the same period. The black middle-class in the city has shrunk; rent has gone up 25 percent as salaries have stagnated. The city has in many ways recovered, but that recovery was not equally distributed, geographically or demographically.

Rivlin has a long piece in this week's New York Times Magazine about the collapse of the city's black middle-class in the wake of the flood, which delves further into the details of what happened, the kind of policy details that garner fewer headlines than charter schools but represent the foundation of a city:

Seven months after Katrina, as McDonald drove me around his New Orleans in a tan minivan, the East was still barren. A new federal program called Road Home had just been announced. Publicized as the largest housing-recovery program in the country’s history — it would eventually grow to more than $10 billion — it promised to pay out as much as $150,000 to homeowners who had flood damage, depending on the size of their losses.

But McDonald had already diagnosed Road Home’s racial bias: Compensation would be based not on the actual cost of rebuilding, but on the appraised value of a property. The cost of restoring a 2,000-square-foot house in mostly white Lakeview, just west of City Park, or Gentilly, a black middle-class neighborhood to its east, would be the same — but the Road Home payment would differ. In Lakeview, that home was valued at a little over $300,000. A Lakeview couple who received a $150,000 flood insurance payment would receive the full $150,000 from Road Home. But in Gentilly, a similar home was valued at closer to $160,000. If a Gentilly couple received a flood insurance check of $150,000, they would receive only $10,000 from Road Home. It wasn’t just the poor, McDonald understood early on, who would have trouble rebuilding, but also middle-class people who didn’t have the savings or family wealth to make up the shortfall and fix their homes.

The decision to compensate based on appraised value, not the money to rebuild, cost the Department of Housing and Urban Development $62 million to settle a lawsuit. St. Bernard Parish settled a lawsuit filed by the federal government over its blood-relation zoning and reduction of multi-family housing zoning for $2.5 million.

The Road Home program also highlights how the city's recovery followed massive amounts of federal aid and the stimulus effects of it. In 2009, the Wall Street Journal found a healthy unemployment rate and an equivalent flood of people rushing to find jobs; while much of the country was suffering as the housing bubble led to a decline in construction jobs, New Orleans was rushing to rebuild:

Unemployment lagged well behind the national average before reaching 7.3% in June, compared with the U.S.'s 9.7%, unadjusted for seasonal shifts. The arrival of non-natives seeking jobs helped New Orleans rank as the U.S.'s fastest-growing big city for 2008, with an 8% increase.

"It's the sheer amount of construction going on," said Nick Perkins, 38 years old, who relocated from New York two years ago and founded The Receivables Exchange, a Web-based trading market for small and midsize companies to raise capital by selling their commercial receivables. Mr. Perkins said he was drawn by the significantly lower cost of living and lifestyle.

"I tell people it's like living in Shanghai because there's big construction going on literally every single day," he said. "The city's getting a full upgrade. I've not seen anything quite like it anywhere."

The construction industry maintained stable employment through the teeth of the Great Recession, as the federal government spent sums the state could not match even in normal times: "The federal money spent on rebuilding south Louisiana in the decade since hurricanes Katrina and Rita is roughly equivalent to what officials in Baton Rouge would typically spend on capital projects statewide over 60 years. Taken together with the emergency aid it provided in the storms’ aftermath, the federal government has spent three times the annual state budget on Louisiana’s recovery."

When floods hit Fargo and Moorhead in 2009, Bloomberg Business's Prashant Gopal asked "Can a natural disaster be a good thing?" in a piece titled "The Natural Disaster Stimulus Plan." A local homebuilder told Gopal that Katrina "saved our butt" because, while the city did not escape the literal storm, it escaped the figurative storm of the housing bubble and recession.

This calculation is absent from McQueary's editorial; given the evolution of federal tax policy and federal block grants over the past decades, it is likely to be absent from any solution to Chicago's problems as well.

What is left is a jarring metaphor: "I can relate, metaphorically, to the residents of New Orleans climbing onto their rooftops and begging for help and waving their arms and lurching toward rescue helicopters." It is jarring because it is, in part, a metaphor for what is almost certain in the end to be a property-tax increase and a slower pension-payment schedule.

It is important to remember, though, that McQueary's prayer for rain is hardly unique. History is littered with cities and countries that have reinvented themselves for the better after natural disaster. The most obvious example for Chicagoans is the Chicago Fire; the city is justly celebrated for its reinvention of architecture in its aftermath, as Chicago, like New Orleans today, became a tempting canvas for talented creatives, as people like Louis Sullivan might be called today, that created the Chicago School. (Of course, like New Orleans, it also came at a cost—zoning changes prohibiting the construction of inexpensive wood buildings displaced immigrants who couldn't rebuild in the central city.)

The journalist Rebecca Solnit provides an alternate example of how to write about such rebirth, with humanity and empathy, in A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster. Solnit surveys those communities from the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 up through New Orleans after Katrina, touching on everything from the small heroics that fed and housed victims to the lasting political changes that stirred citizens to challenge the governments whose shortcomings added to the crisis.

"The organization of the colonias/barrios was clearly strengthened. There was this feeling you had the world in your hands, beyond army or government. Really, this country awakened after the [Mexico city earthquake of 1985]," activist and post-development theorist Gustavo Esteva told Solnit. "Ordinary men and women can take things in their hands. Suddenly we saw that the people themselves were having real agency. In the late 1980s they were doing marvelous things."

This "imaginative complicity with disaster," as a result, is quite powerful, because so many have seen and been a part of those extraordinary communities, as my friend Athenae, one of the many volunteers to do some part in rebuilding after Katrina, recounts in a moving piece. "They brought me drinks and food and asked about me and my life. They told me about theirs, why they lived there, what they loved about it. They hugged me and said thank you for caring about us, and I was ashamed of my blisters and my exhaustion," she writes. "I know at least three of them are dead now."

Where is that line, between metaphor and desire? Here is where Solnit places it.

Disasters are, most basically, terrible, tragic, grievous, and no matter what positive side effects and possibilities they produce, they are not to be desired. But by the same measure, those side effects should not be ignored because they arise amid devastation. The desires and possibilities awakened are so powerful they shine even from wreckage, carnage, and ashes. What happens here is relevant elsewhere. And the point is not to welcome disasters. They do not create these gifts, but they are one avenue through which the gifts arrive. Disasters provide an extraordinary window into social desire and possibility, and what manifests there matters elsewhere, in ordinary times and in extraordinary times.

But as Solnit readily admits, not all that occurred after Katrina is so devoutly to be wished. The fear propagated in the months and even years after the storm reopened wounds that were inflicted decades before landfall, that remain open today, and was no more true than narrowly ameliorating myths of "hitting the reset button." The least that outsiders can do—and it is, in context, profoundly little—is attempt to do an honest appraisal of history, and to bring its lessons forward not as metaphor, but reality.