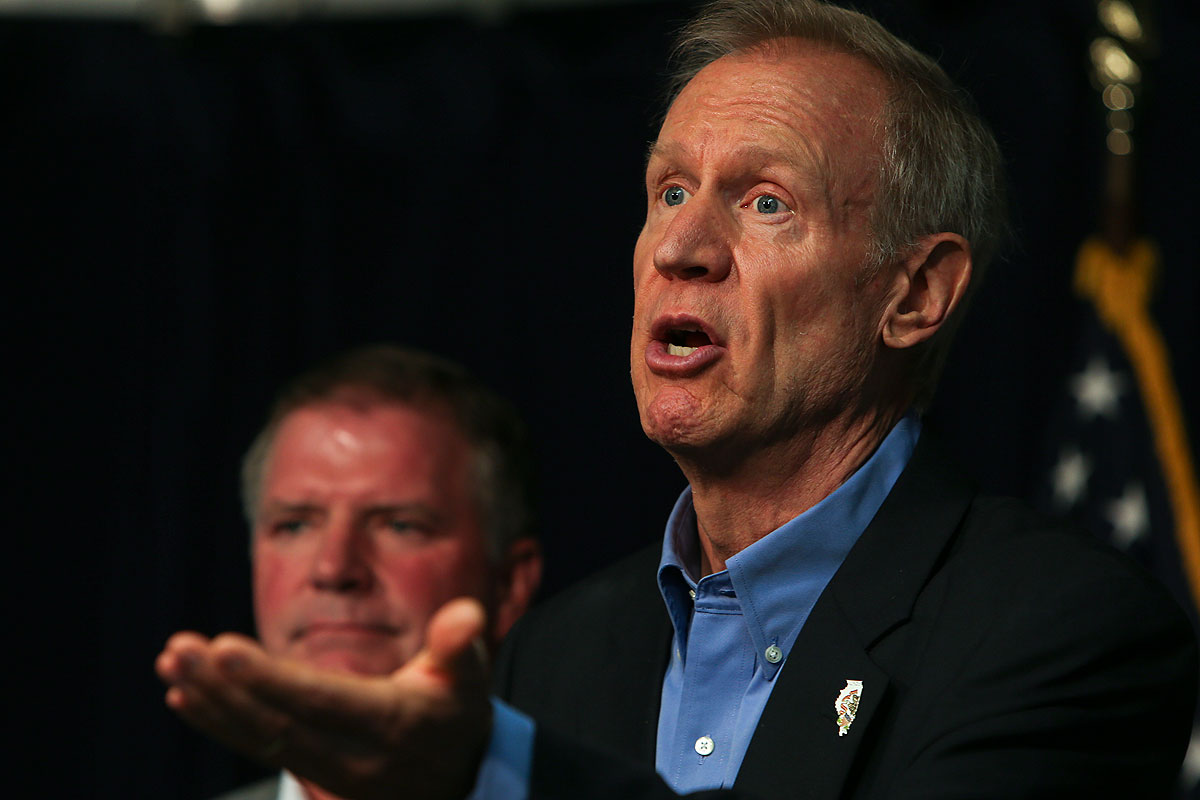

Two months ago, the Illinois legislature overrode Bruce Rauner's veto, giving the state a real budget for the first time in two years.

It was widely viewed as a considerable political loss for the governor, and about a week later Rauner purged his staff, casting out a number of political veterans in favor of an influx of staff from the Illinois Policy Institute, a prolific libertarian/free-market/conservative think tank that rose to greater prominence after Rauner gave half a million dollars to the group between 2008 and 2013.

Rauner's use of the IPI as a farm team in the aftermath of the budget override caused many to speculate that the governor would double down on the remaining parts of his diminished "turnaround agenda" and continue his trench warfare against the Democratic-led legislature, even though the override suggested the governor would remain at a disadvantage.

Then the IPI posted a cartoon to its website. And suddenly things started to shift.

To make a long story short, the IPI's cartoon made a point that many people on the opposite end of the ideological spectrum have argued: that tax-increment finance districts take money away from Chicago public school students. (Here's a good piece from UIC professor Rachel Weber, an expert on the subject, about how that argument is plausible but complicated.)

But the drawing itself was described as racist. Reporters—particularly Mary Ann Ahern—pushed Rauner to respond to the cartoon, as Rauner was not only a previous large donor to the IPI but had just recently hired away several people from its staff. His new, IPI-heavy team kicked the can, even while legislators from both parties condemned it.

Then, last Tuesday, as Rauner was away moving his kid to college, his new staff released a statement that read, in part (emphasis mine):

The governor has great respect for the black caucus and members of the General Assembly who voiced concerns about the cartoon. The governor’s office has also heard from members of the black community who found truth in the imagery and do not find the cartoon offensive. Here is where things stand: The cartoon was removed days ago. And the governor – as a white male – does not have anything more to add to the discussion.

The fixation on this cartoon and the governor’s opinion of it has been disappointing.

That hamfisted line obviated the one that followed, and the governor released another statement, disavowing the previous statement, which, reportedly, had not been run past him: "Earlier today an email went out from my office that did not accurately reflect my views."

Rauner subsequently fired his newly hired communications staff.

Meanwhile, as this was consuming all the oxygen in Springfield, legislators were trying to pass funding for arguably the most politically consequential of all government funding: K-12 schools. This was made more complex because the vehicle for doing it was a major reform bill, SB1.

The bill, sponsored by Democrat Andy Manar, was a major legislative achievement that survived the chaos of the budget debate, addressing the state's inequitable funding of schools. Because school funding in Illinois is so dependent on property taxes, districts with a great deal of property wealth typically have generously funded schools. Districts with low property wealth not only have poorly funded schools, but often have high property taxes as well, because the tax rate required for even modest funding has to be substantial. Furthermore, those districts typically have more students with a greater need of services, such as special-ed students and English-language learners.

SB1 addressed this through "adequacy targets," which would determine the amount of state aid granted to districts using demographic data. It also included a "hold harmless" provision so that districts would not lose out on state funding. The idea is that the winners under the old formula wouldn't lose, and the losers under the old formula would win.

Republicans backed a bill that would send less money to Chicago Public Schools, but Manar's bill passed through the legislature. Rauner gave it qualified support, saying he'd support it "with very little tweaks."

Then things got weird.

Rauner, as expected, issued an amendatory veto of Manar's bill. But the tweaks were not "very little." And that's where the cartoon comes in. One of Rauner's changes would take into account PTELL (the complex Property Tax Extension Limitation Law) and tax-increment finance districts, better known as TIFs, into account when determining school districts' property wealth.

As I mentioned, there's a debate as to whether TIFs take money away from schools. But they do suck up property-tax money and at least restrict how it can be spent on schools. So they're not counted in the equalized assessed value of a district's property wealth. The IPI has argued that this means districts that are covered by TIF districts thus have their property wealth undervalued, and thus have an unfair advantage over districts that don't use TIFs. Among other things, Rauner's amendatory veto, if the legislature passed it into law, would mean that districts using TIF and PTELL would lose out.

But Rauner made a mistake: he underestimated how many votes it would take to pass his amendatory-veto changes, a mistake that came immediately on the heels of his first staff shake-up.

Rauner told reporters it would take a simple majority of legislators to approve his changes. But Democrats, citing a previous attorney general's opinion, say more votes are necessary because the law would have to take effect immediately in order to get money to schools.

The Senate, which had passed SB1 with a veto-proof majority, overrode the veto. Now it has to get through the House, where reaching a three-fifths majority is more difficult. So the two sides are trying to hammer out a compromise to clear the higher bar Rauner accidentally set.

And Politico's well-connected Natasha Korecki reports that, under the developing compromise, "SB1 will change very little." After the budget mess, the hiring of IPI staffers suggested Rauner would dig in. But now it appears that legislative Democrats (and Mayor Rahm Emanuel) could get a big win.

Why? A drawn-out fight to get a three-fifths majority in the House would cause schools to start shutting down as they wait for funding, which would be politically catastrophic for Rauner. Plus, the cavalcade of errors—the first staff shakeup, the miscalculation on amendatory veto votes, the failure to quell the unexpected cartoon mess, the second staff shakeup—further weakened the governor's political standing.

But another reason is that Rauner's amendatory veto could be unpopular downstate. Thanks in part to the cartoon, the TIF debate has centered around Chicago, but there are many downstate counties that also use TIF districts as much or more than we do.

"Our analysis found six counties that have a higher percentage of the county that has TIF than even Chicago," says Bobby Otter, the budget director for the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, which has weighed in in favor of SB1. "Chicago's the poster boy of this, but you look at some of these downstate districts, and they're more so TIF'd in many cases. What that's going to do is reduce the amount of money that those districts would be eligible for. Clinton, Ford, St. Clair, Johnson, Williamson, and Grundy all have a higher percentage that's in a TIF district than Chicago."

It sets up a curious political dynamic, as Eric Schelkopf reported for the Kane County Chronicle when SB1 was first introduced:

State Rep. Steve Andersson, R-Geneva, said Senate Bill 1 is not any better than Senate Bill 16. Local legislators last year criticized Senate Bill 16 for penalizing suburban school districts.

State Sen. Karen McConnaughay, R-St. Charles, was one of the legislators who had opposed Senate Bill 16. At the time, McConnaughay said the bill generally would favor Chicago and downstate communities and would reduce state distributions to many suburban school districts.

“It tries to address some of the objections that were made by creating a hold harmless provision, which basically says that if you’re a loser in this equation, we will somehow bolster that,” Andersson said. “About the only thing I agree on this is that I agree that there has to be a fundamental review of education funding in the state of Illinois.”

The TIF/PTELL changes weren't the only parts of Rauner's amendatory veto that could hurt less-wealthy school districts. Under new law, districts have to start picking up teacher pension costs, as Chicago does now. SB1 would take those costs into account when calculating state aid; Rauner's amendatory veto stripped that provision. That went over about as well as you'd expect.

"This is going to be a totally new cost for all the districts in the state, other than CPS, of course," Otter says. "So now districts would have to find the funding to start paying for their teachers' normal cost at the local level, or using state funding to do so, but it's not in the funding model, so you're going to see districts' cost rise."

So while the rhetoric over SB1 has set up the usual Chicago-versus-everyone else cliché, the actual substance of Rauner's amendatory veto results in a more complex dynamic, one that puts the governor somewhat at odds with districts in Republican areas.

In exchange for a relatively clean passage of SB1, Rauner and his allies would get one win: a bill that would give generous tax credits for donations to private-school scholarship funds targeted to lower-income students. It's an idea that will be anathema to progressives, for reasons that Eric Zorn makes clear in a thorough argument against it. Rich Miller reports, "I’m hearing that the House Democratic teleconference meeting today was 'brutal' on this topic." But any school-funding bill passing the House will have to be substantially bipartisan, so a clear win on SB1 will require political compromise from Democrats, who are likely to get limits on the tax credits.

Meanwhile, a non-trivial number of Republicans will have to stay in line for a bill to pass, and the most recent line from the governor is that, while the sides are close and he favors the funding formula, it's still a Chicago bailout. "It’s not fair, but it’s going to end up being a compromise. It’s not where we’d like it to be, but what I’ll try to do is fix the problems with it in subsequent legislation," he said in a speech Friday. WTTW's Amanda Vinicky, as knowledgeable a reporter as there is in the capital, floated the idea that such talk could "scuttle a deal" that, at best, will be extremely fragile.

The House is scheduled to convene today for a final reckoning. Between Rauner's language and progressive backlash to the tax-credit provision, any deal will be on thin ice. Hopefully no one will publish any more cartoons in the meantime.