Who was Eugene Williams? The black teenager’s death sparked Chicago’s 1919 race riot, but few facts are known about Williams himself. He died in the waters of Lake Michigan on the afternoon of July 27, 1919, after a white man threw rocks at him — a tragedy that spiraled into a spate of violence lasting several days, with 38 people dead.

At the time, when newspapers reported on the riot, they mentioned Eugene Williams’s name, but nothing about his story, his parents, how his death changed their lives. As far as I can tell, after searching through microfilmed and digitized newspapers, the press didn’t bother to answer those questions.

This was typical of journalism in the early 20th century. For one thing, few newspapers reported in depth about the lives of black Chicagoans. But even the Chicago Defender, a nationally prominent black newspaper, said very little about Williams. Furthermore, newspapers rarely told detailed stories about anyone’s lives.

The Defender (whose historic issues are searchable with a Chicago Public Library card) did publish a picture of Eugene Williams (shown above at right) on August 30, 1919, a little more than a month after his death. A smiling young man in formal clothing is dimly visible on the microfilm and digital scans. Whether it’s a graduation picture, a family portrait, or something different, I don’t know.

The short text below the picture noted that Williams had lived at 3921 South Prairie Avenue, the same address that the Defender mentioned in its first report about his death. That’s one of the only scraps of information published about Williams at the time.

“Little is known of his parents or his early life,” according to the African American National Biography. Nevertheless, Williams was considered important enough to merit a short biographical entry in that 2006 reference collection.

In 1919, Eve L. Ewing’s new book of poems about the riot, she imagines a black man named James Crawford witnessing Eugene Williams’s drowning. Crawford sees Williams clinging to a railroad tie in the water. He muses that no one would be saying Eugene’s name if he hadn’t drowned. “… but he was somebody, / because I saw the whites of his eyes / before he let go of the railroad tie. / So I spoke it, his name came out of me, / and I fired.”

It isn’t known whether the real-life James Crawford witnessed Williams’s death. But he reportedly did fire a gun at police later that day. A cop killed Crawford — the second death of the riot.

As the poem’s narrator says, Eugene Williams was somebody. And as I was researching my recent Chicago magazine article chronicling the race riot, I found a few more details about him.

During my reporting, I contacted William M. Tuttle Jr., the author of the 1970 book Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919. Now 81, he’s a University of Kansas professor emeritus.

Tuttle agreed to mail me the transcripts of some interviews he’d conducted in the late 1960s for his book. Among them was a conversation with John Turner Harris, a friend of Eugene’s who’d been there on the day he died.

In them, Tuttle asked Harris, “Can you tell me much about Eugene Williams, what kind of guy he was?”

Harris responded: “He was just a regular kid like us — just a regular kid … He had just graduated from school … He was a pretty smart boy. That’s all I know. As I say, we met him and we liked him.”

Harris noted that Eugene lived in a different neighborhood than he did, so he might not have known him all that well. It isn’t clear where Eugene attended school. Had he been a recent high school graduate, which we don’t know, it’s likely he would have attended Wendell Phillips High School, just one block north of that address on Prairie Avenue.

One puzzling clue: According to Harris, Eugene attended a school that was later turned into “a health center.” Tuttle told me he thinks Harris was alluding to Michael Reese Hospital, but I haven’t found anything about a school that became part of the hospital’s campus.

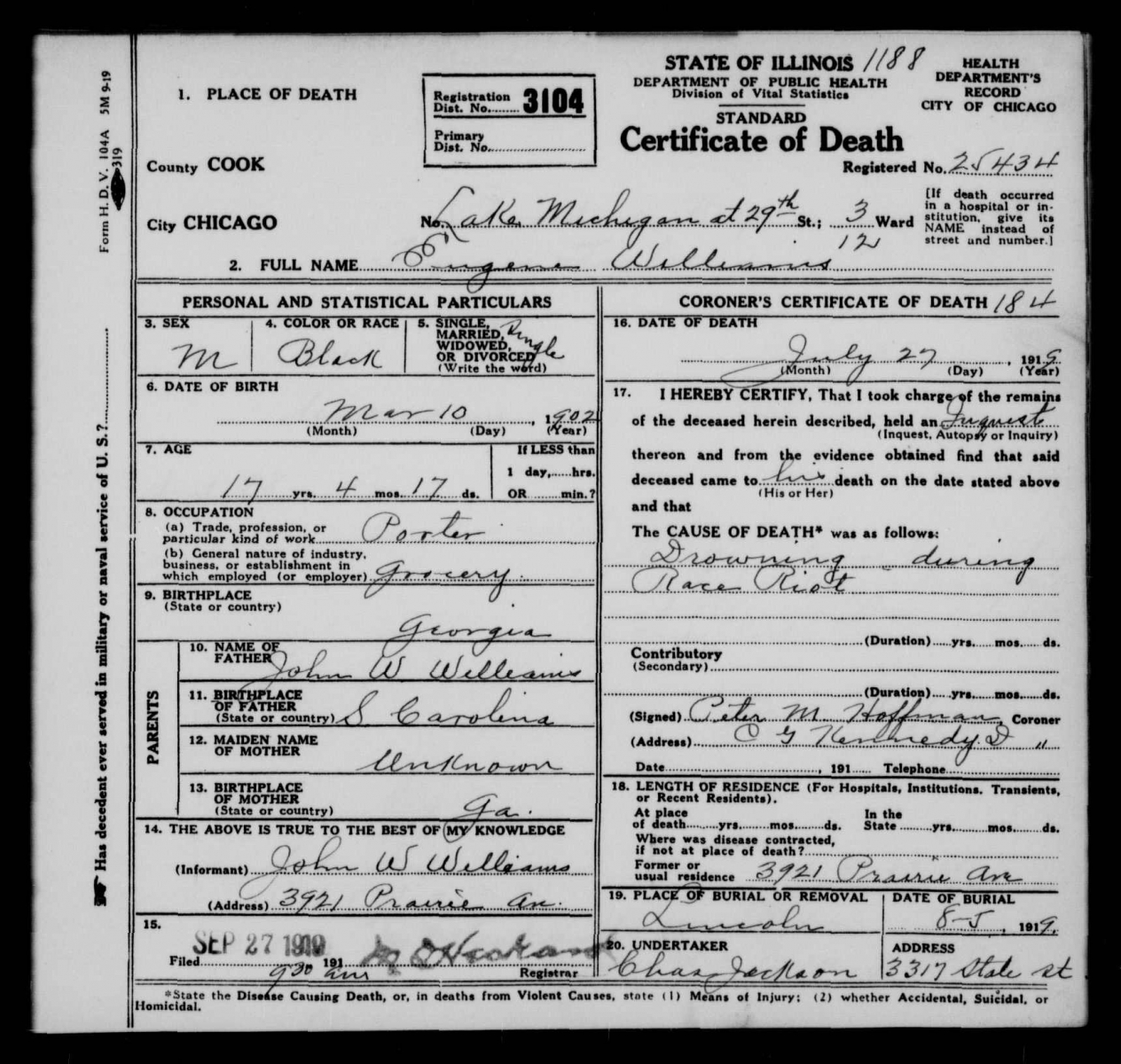

Author Claire Hartfield’s 2018 book A Few Red Drops: The Chicago Race Riot of 1919 includes a reproduction of Eugene Williams’s death certificate from the Cook County clerk’s office. (It’s also posted at findagrave.com.)

Here’s what we know about Williams from that document: He worked as a porter at a grocery store. He was born on March 10, 1902, in Georgia. His father, John W. Williams, was born in South Carolina. “Unknown” is written in the space for “Maiden Name of Mother,” but the document does say Eugene’s mother was born in Georgia. Other records show that her first name was Luella.

The death certificate also says that Eugene was buried at Lincoln Cemetery on August 5, 1919, nine days after his death. The undertaker was Charles S. Jackson of 3317 South State Street, a black Pittsburgh native who was well regarded in the African American community. (After 145 years in business, becoming America’s longest-running black-owned funeral home, the Charles S. Jackson Funeral Home’s final South Side location closed in 2012.)

During his interview, Harris recalled his friend’s funeral, explaining why he never told investigators about the drowning he’d witnessed. He was afraid, he said, that his mother would get angry if she found out he’d disobeyed her by going swimming.

“I’ve never told it to the police or anything,” Harris told Tuttle. “We were forbidden to go swimming on Sunday, and I was more afraid of my mother than anyone. They would look for us and ask who the boys were with him. We went to the funeral, and the mother knew me. And when I talked to her at the funeral, I told her how it happened.”

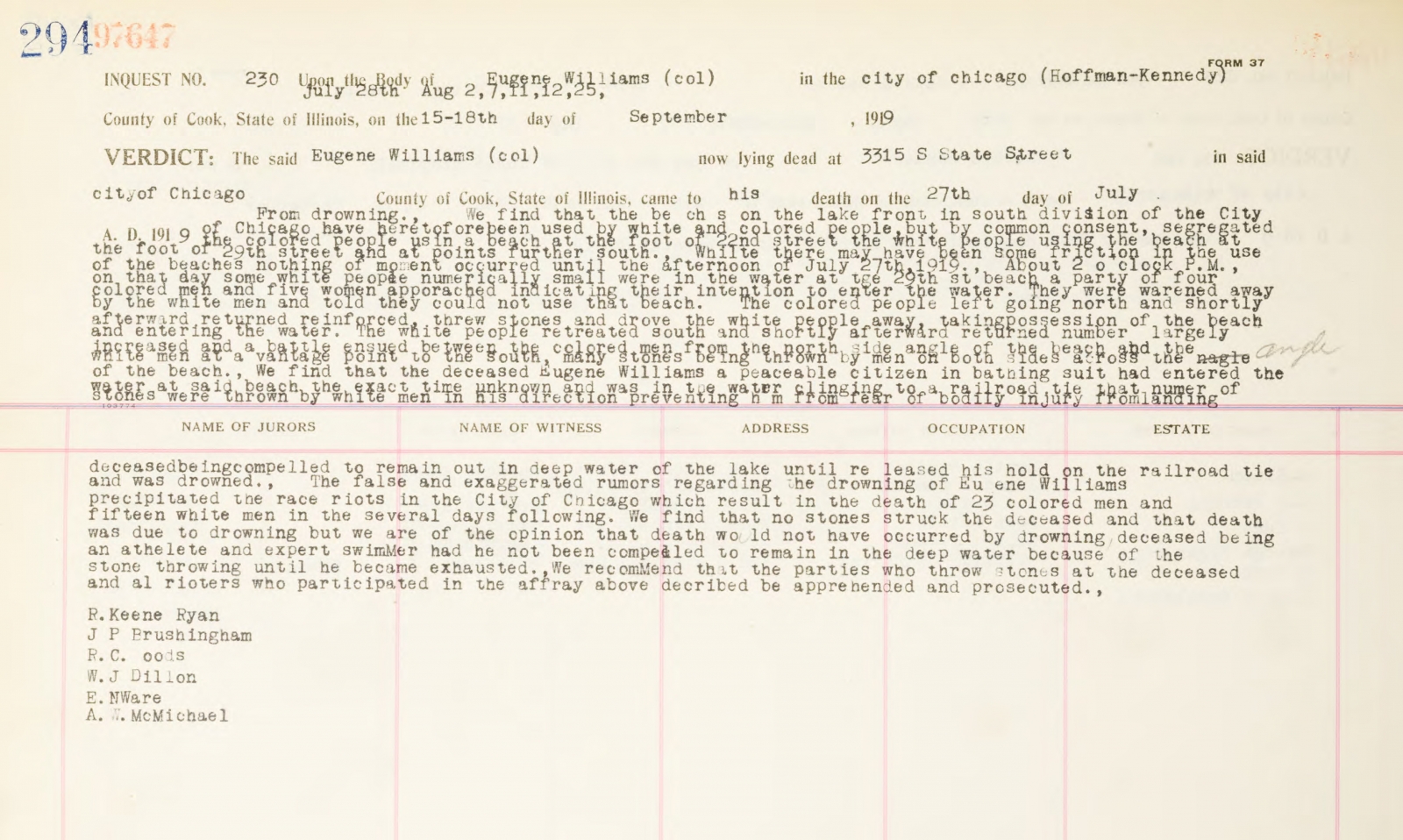

Harris believed that Luella Williams later conveyed his story to the authorities. But it’s unknown exactly who testified when Cook County coroner Peter Hoffman held an inquest to determine the cause of Eugene’s death. Many documents about the race riot are missing — including 5,584 pages of testimony that witnesses gave at coroner’s inquests for the 38 homicides.

I filed a Freedom of Information Act request in November 2018 with Cook County, asking for any surviving documents connected with those deaths. Five days later, they’d found coroner’s jury verdict forms for 35 of the 38 homicides. (These verdicts were also published in a report you can see at the Chicago History Museum.)

In its verdict concluding that Eugene Williams had drowned, the coroner’s jury described him as “a peaceable citizen in bathing suit.” But what about those thousands of pages of testimony?

Rachel Dailey, the administrative assistant in Toni Preckwinkle’s office who handled my FOIA request, told me via email: “After an extensive search we have not located any additional records responsive to your request. We will continue to search for records and contact you if and when they are located.”

Five months later, I asked if any additional documents had turned up. “No luck finding anything else,” she replied.

The coroner’s jury described Williams as “an athlete and expert swimmer.” Did someone testify to the jury about Eugene’s athletic prowess? In his interview, Harris said: “None of us were accomplished swimmers, but we could dive underwater and come up. We would push the raft and swim, kick, dive, and play around. As long as the raft was there, we were safe.”

The story Harris told about that raft offers another glimpse of what Eugene Williams was like. “We made a little raft, we worked on that a long time,” Harris said. “About four different groups of about 20 boys worked on this raft for about two months. It was a nice size — it was about 14 by 9 feet. Oh, it was a tremendous thing.”

This was possibly a typical hobby of teenagers of that era. I’ve read stories about white Chicagoans on the North Side doing the same thing in the late 19th century. In 1891, a city official complained about boys constructing ramshackle rafts with scraps of lumber and using them to float in the flooded holes left behind when brick makers scooped clay out of the ground. This was especially a problem in Lake View. “The small boy delights in tormenting his mother by exemplifying the illustrations in his ‘Robinson Crusoe,’” wrote Walter V. Hayt, the general sanitary officer in the city’s Department of Health. “He constructs rafts of odds and ends of lumber, and boldly sets out from shore. As a general rule he comes home drowned before night, on a stretcher manned by two burly policemen.”

It’s likely that Eugene and his friends were just looking for ways to spend their free time. They knew that white people used the 29th Street beach, while black people used a section of beach farther north, near 25th Street.

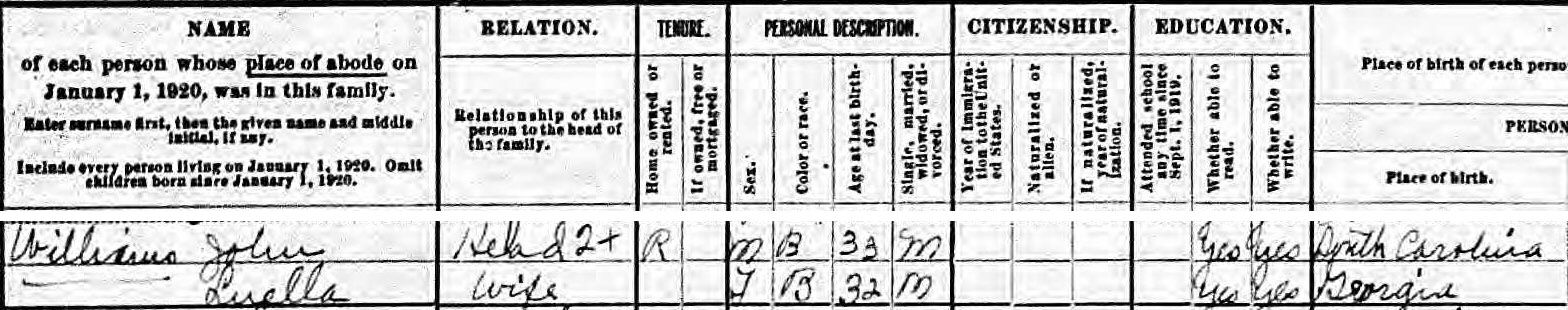

There’s some mystery about exactly where Eugene Williams lived and when. Five months after the race riot, when enumerators for the Census came through Chicago’s Black Belt neighborhood (now part of Bronzeville), the Williams family was not living at 3921 South Prairie Avenue. The occupants then were a self-employed house decorator named John K. Goodwin, his wife, Annie, a billing clerk for a mail order house, and their three children. They had a mortgage on the property.

According to Chicago city directories — which listed the home addresses and occupations of city residents — Goodwin had moved into the house seven or eight years earlier. He was still at the same place in 1935, when he took out an ad in the Defender offering his painting, decorating, paperhanging, and wood-refinishing services.

The building apparently included a second dwelling unit. A Sanborn fire insurance map from 1895 (one of those marvel old atlases with the outlines of buildings) shows a two-story brick dwelling with a basement at this address — in other words, a two-flat.

If you visit the 3900 block of South Prairie today, the east side of the street is mostly vacant lots, including the spot where the Goodwins once lived. Their building probably resembled a two-flat building that’s still standing nearby, at 3913 South Prairie.

In a recent Chicago story, AJ LaTrace described how two-and three-flats “were seen as a path to the American dream—an opportunity to build equity and achieve financial security through rental income, with the homeowner living on one floor and tenants living on the others.”

As the Goodwins paid off their mortgage, they apparently rented one of the floors to tenants — in all likelihood, the Williams family.

(When he talked with Tuttle half a century later, Harris recalled Williams living at a different address. “Eugene lived at 3157 Wabash,” he said, mentioning the address twice. Either Harris was mistaken, or Eugene had lived there at some other point.)

Out of sheer luck, I stumbled across Eugene’s parents in the 1920 census. I was curious about the Angelus Apartments — a seven-story building where one of the riot’s most violent episodes took place — so I looked it up in the census on Ancestry.com. (It’s also searchable at FamilySearch.org.)

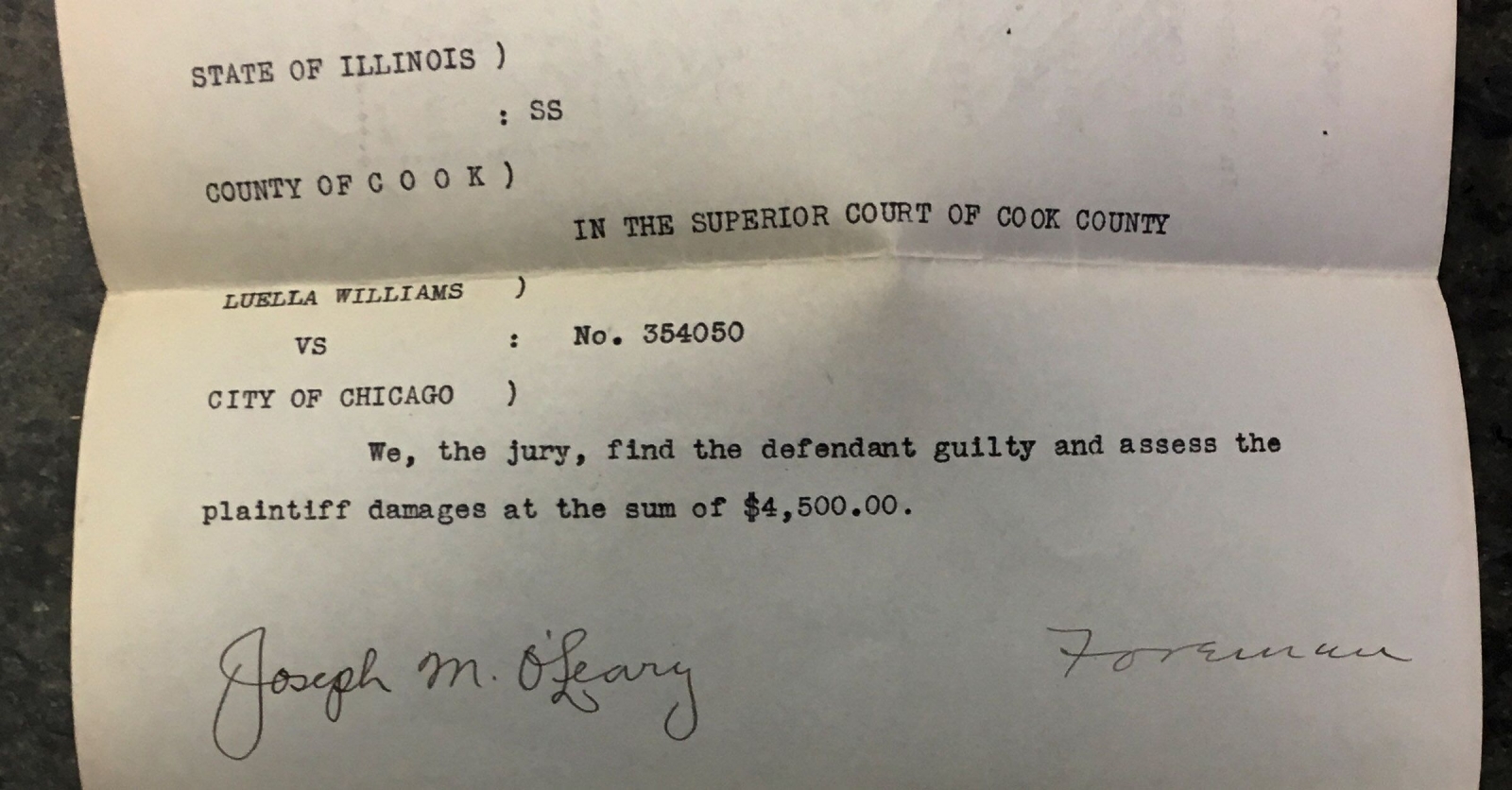

Scrolling through the hundreds of residents in the building, I noticed an entry for John and Luella Williams. Their address was 3501 South Wabash Avenue — possibly their residence after their son’s death. Luella’s name also appears in Chicago City Council minutes from 1923, when the aldermen voted to settle lawsuits filed by Luella and other relatives of race riot victims, paying them $4,500 each.

The lawsuit notes that Luella’s son was earning $18 a week at the time of his death — about $460 in 2019 dollars. The document includes a space where the lawyers should have written the name of Eugene’s employer, but they left it blank. The lawsuit also describes Luella as Eugene’s “only heir and next of kin, who was solely dependent upon him for her support, aid, and maintenance, and who has by reason of his death been deprived of the said support, aid, and maintenance.” This suggests her husband had also died.

Using information from Ancestry.com and an Illinois State Archives deaths database, I pinpointed a date for John Williams’s death and requested a Cook County death certificate. It showed that he died of aortic regurgitation on March 31, 1921 — only a year and a half after his son’s death. “About” 36 when he died, he’d been born in 1884 or 1885 in South Carolina, just two decades after slaves were emancipated.

John’s parents, Wesley and Lilla Williams, were also from South Carolina, probably born around the time of the Civil War. John had a job that was common for black men of his era, working as a dining car waiter on the Rock Island Line.

The death certificate says that John had lived in Chicago for 12 years, meaning that he’d arrived sometime in 1908 or 1909, when his son, Eugene, was six or seven years old. That’s several years before what historians regard as the beginning of the Great Migration of African Americans.

Looking through Chicago city directories, I found a possible match for the Williams family in the 1912 directory. A porter named John W. Williams was living with a Luella Williams at 3512 South Calumet Avenue, where a North Carolina native named J.T.N. Patterson rented out rooms.

It appears that Eugene had no siblings, or at least none that were living with his parents at the time of his death. Census records show that Luella was born in 1888 in Georgia, but her maiden name and ancestry are a mystery. It’s also unknown when or where she died, or how she spent the remainder of her life. (She might be one of the six people named Luella Williams who died in Chicago between 1923 and 1943. There were also seven people listed as “Lula Williams” who died in Chicago during that period.)

Conjuring Eugene Williams’s childhood experience takes some guesswork. Most black Southerners moved north to escape racist Jim Crow laws and the threat of lynching, while hoping to find better jobs, schools, and homes. On one hand, Defender articles from Eugene’s childhood describe a vibrant community of black Chicagoans living on the South Side at the time. On the other, complaints were common about shoddy and unsanitary housing.

How much racism did Eugene experience during his life — as a child in the South, and later as a youth on the South Side? Black Chicagoans faced insults, threats of violence, and even bombings when they moved into neighborhoods previously dominated by white people. Harris recalled white gangs such as Ragen’s Colts attacking black youths whenever they ventured into white neighborhoods.

It’s possible that more documents on Eugene Williams are out there. Digitization has made has it far easier to search historic newspapers and genealogical records, but many aren’t available online. Some aren’t even on microfilm. And it’s conceivable that somewhere, someone has old letters or diaries sitting in an attic or closet that would shed light on Williams’s story.

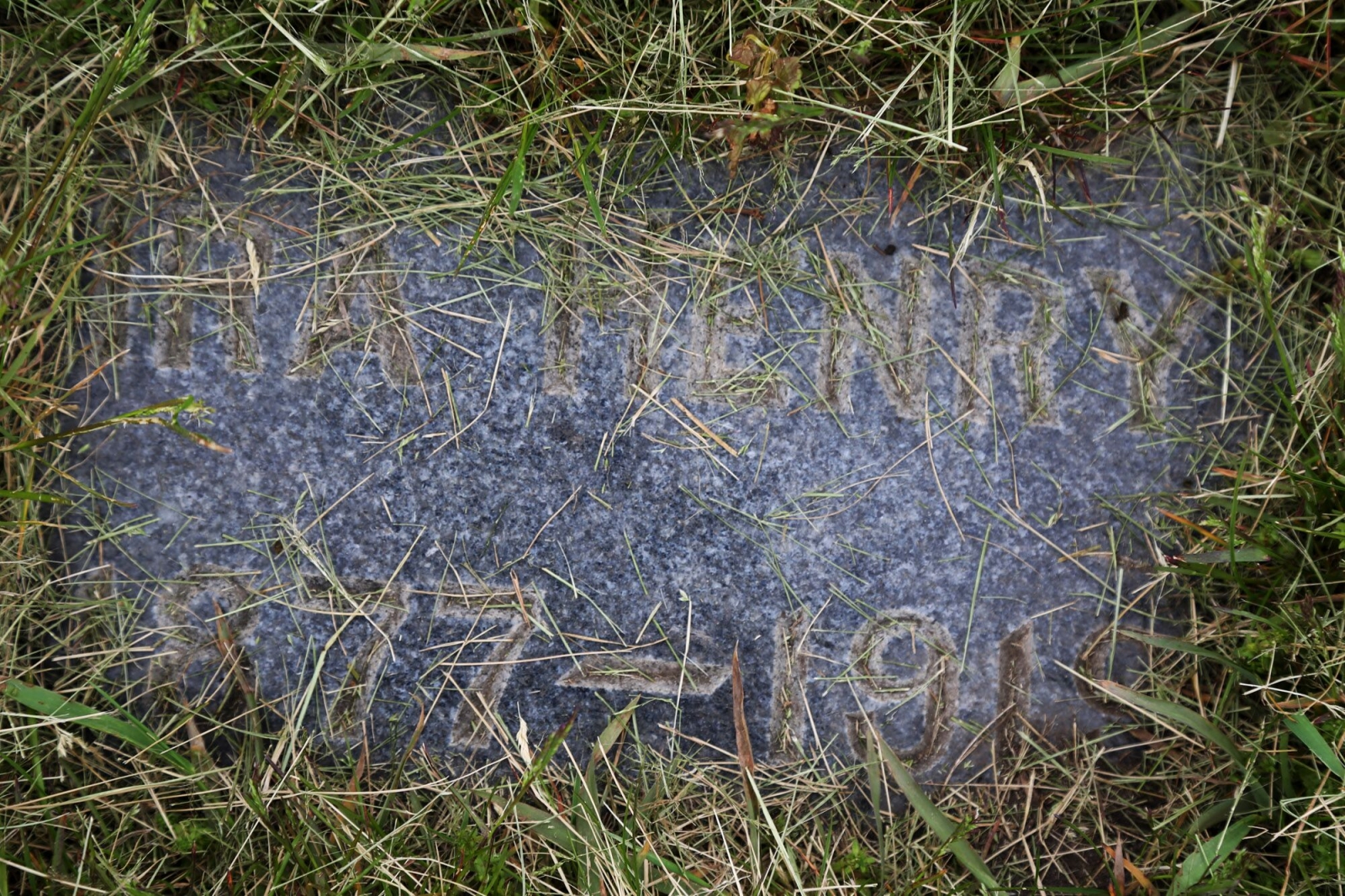

In May, I called the offices of Lincoln Cemetery, asking for the location of Eugene Williams’s grave. A cemetery employee looked him up and gave me these coordinates: Section 5, Lot 30, Row 6, Grave 36.

“Is that the boy who died in the riot?” she asked.

I drove out to Alsip the following morning to visit Lincoln Cemetery. Among the famous black Chicagoans who are buried there: poet Gwendolyn Brooks, Defender founding editor Robert Sengstacke Abbott, aviator Bessie Coleman, congressman George Washington Murray, actor Richard Berry Harrison, Negro Leagues baseball star Rube Foster, and musicians Albert Ammons, Gene “Jug” Ammons, Lil Hardin Armstrong, “Big Bill” Broonzy, Johnny Dodds, Baby Dodds, Al Hibbler, Bertha “Chippie” Hill, Jimmy Reed, Jimmy Yancey, and Marvin Yancy.

The cemetery opened in 1911, eight years before Eugene’s death. An “Announcement Extraordinary!” in the Defender declared, “This cemetery will be dedicated by the colored citizens of Chicago and vicinity for the burial of their relatives and friends.”

I spent an hour walking around Section 5, looking for Eugene Williams’s headstone, without any success. Then an employee in the cemetery office dispatched a groundskeeper to help me.

The burial plot is in a corner of the cemetery without any trees or shrubs. There are no monuments visible above the grass in — only a few headstones here and there, sitting flush with the lawn and sometimes hidden beneath it. As I walked down the rows, I noticed that all of the visible markers were from 1918 and 1919.

When I was close to the spot where Williams’s grave should be judging from what I’d seen on the groundskeeper’s map, I noticed a marker for someone named Ira Henry, who died in 1919. I recognized the name as that of another race riot victim. A black laborer who’d moved to Chicago from Mississippi, Henry was shot and killed by two police officers near 49th and State Street after he’d shot one of the cops, according to the coroner’s jury. Like Luella Williams, Henry’s family received a $4,500 settlement after suing the city of Chicago.

There were no markers in the grass next to Henry’s, so I went to the cemetery office and asked the employees to look up Henry’s name. A woman looked through the rows of little yellow cards and pulled out the one with his name on it: Section 5, Lot 30, Row 6, Grave 35 — right next to Eugene Williams’s unmarked resting place, 36. A woman in the cemetery office said that somebody else who’d recently inquired about Williams had talked about getting a headstone for him.

Currently, there is a marker bearing Williams’s name elsewhere, not far from where he died in Chicago. It’s on a boulder near the spot where 29th Street would hit the lakefront if it continued east of Lake Shore Drive. The plaque, created in 2009 and sponsored by students from York High School in Elmhurst with the Chicago Park District, is “Dedicated to all the victims of the race riot that began near this place.” Along with a description of Williams’s death and the riot, the plaque features quotations from the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

The boulder is easy to miss if you aren’t looking for it. It sits in the grass near a walking trail a short distance west of the water — south of McCormick Place and north of the Margaret Burroughs Beach at 31st Street. The landscape has changed since 1919, as landfill was added along the shore. The shoreline where Williams, Harris, and their friends waded into the water was approximately where Lake Shore Drive is today, and the place where Williams drowned was probably farther north.

When I stopped by the boulder in late July, butterflies were flitting nearby amid milkweed, prairie grass, and flowers. A handful of Chicagoans of various races were enjoying the mild, sunny weather that Monday. Some sat on the concrete embankments near Lake Michigan’s waves, others strolled or jogged on the nearby paths. In front of the rock with Eugene Williams’s name, someone had left a circle of flowers.

Comments are closed.