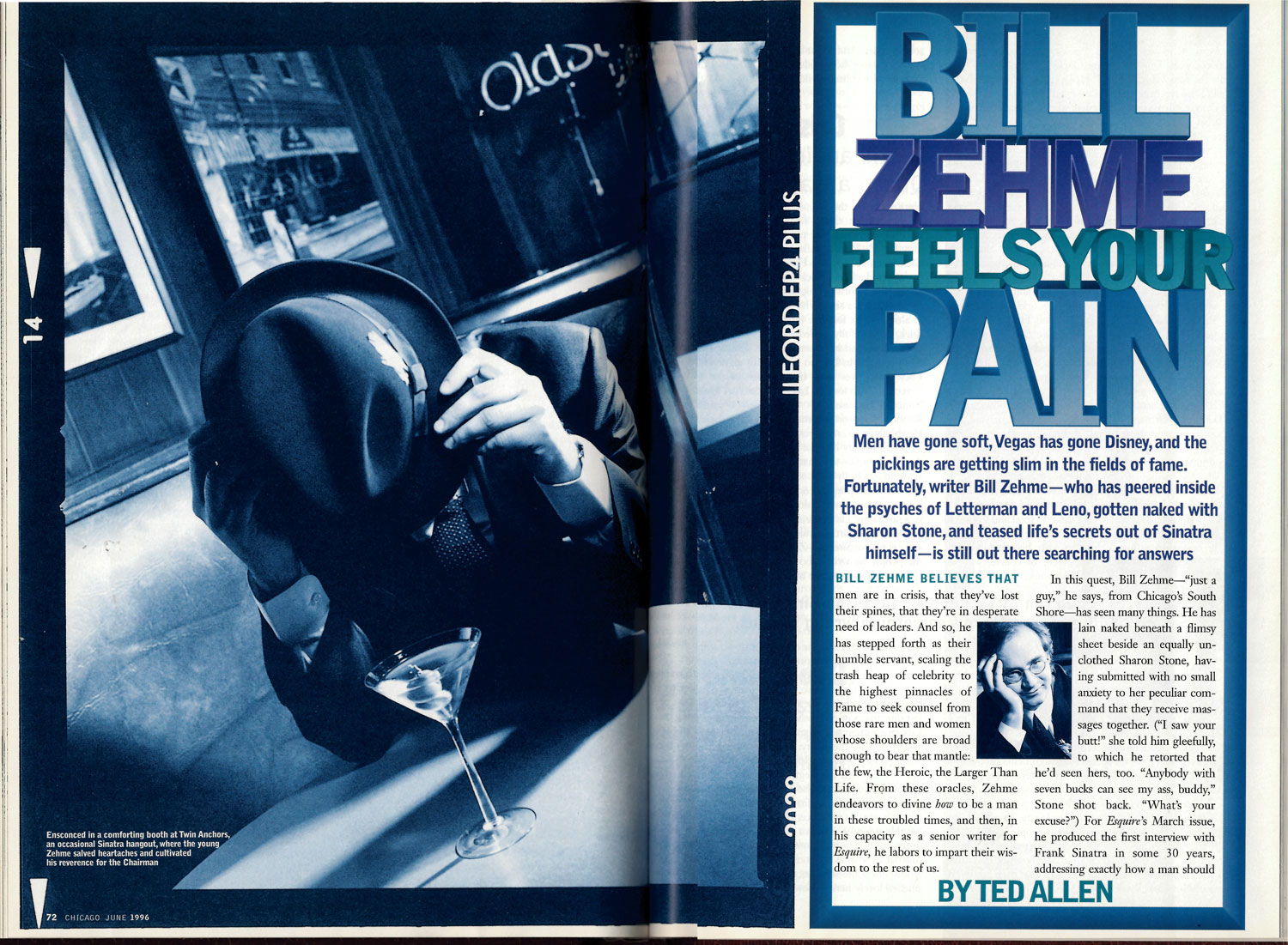

Editor’s note: This article originally published in the June 1996 issue of Chicago. Zehme died on March 26, 2023, at 64 from cancer.

Related Content

Bill Zehme believes that men are in crisis, that they’ve lost their spines, that they’re in desperate need of leaders. And so, he has stepped forth as their humble servant, scaling the trash heap of celebrity to the highest pinnacles of Fame to seek counsel from those rare men and women whose shoulders are broad enough to bear that mantle: the few, the Heroic, the Larger Than Life. From these oracles, Zehme endeavors to divine how to be a man in these troubled times, and then, in his capacity as a senior writer for Esquire, he labors to impart their wisdom to the rest of us.

In this quest, Bill Zehme — “just a guy,” he says, from Chicago’s South Shore — has seen many things. He has lain naked beneath a flimsy sheet beside an equally unclothed Sharon Stone, having submitted with no small anxiety to her peculiar command that they receive massages together. (“I saw your butt!” she told him gleefully, to which he retorted that he’d seen hers, too. “Anybody with seven bucks can see my ass, buddy,” Stone shot back. “What’s your excuse?”) For Esquire‘s March issue, he produced the first interview with Frank Sinatra in some 30 years, addressing exactly how a man should behave so as to become cool. He also got the last extensive interview with The Great One, Jackie Gleason, for Playboy before the actor’s death in 1987. He has plumbed the psyches of Arnold Schwarzenegger (“Men are in crisis, whereas he is not”), and Woody Allen, crisis personified, who was asked by a fan on the street after his fall from grace, “So you’re the great Woody Allen?” “Well,” Allen replied, “I used to be.” He has consulted Jerry Seinfeld about nothingness, probed the dirty mind of Madonna, gleaned great understanding from Warren Beatty’s long pauses before answering questions, lunched with Liberace for Rolling Stone, attempted to fathom how David Copperfield ended up with Claudia Schiffer, skied with Geraldo Rivera, stroked a snow leopard with Siegfried & Roy, and undergone therapeutic heart-to-hearts over breakfast with Barry Manilow, whom he has described as the hippest man in the world (“Weekend in New England” gives Zehme goose bumps). He wrote the liner notes for the 1994 Sinatra album Duets II. He has cowritten a gag book about guys named Bob and coauthored an autobiography of Regis Philbin, and both works, amazingly, not only sold very nicely but were actually good. He also has served as a guest host on the CNBC show Talk Live, on which he caused Philbin to display one of his naked feet, of which the Rege-ster is very proud. And he delivers a quirky Hollywood report each Thursday morning with his pal Bob Sirott on Fox Thing in the Morning.

Perhaps most notably, he has written the definitive profiles of David Letterman, television’s tortured superstar, and Letterman’s friend-turned-rival Jay Leno — crackling, insightful pieces that revealed, among many other things, that Leno’s consummate careerism belies his image as a befuddled regular guy who was manipulated by his former manager.

Which brings us to the present, in which Zehme and I are lounging with Leno backstage before one of the comedian’s March performances at the MGM Grand Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. Somehow, Zehme’s rather tough piece on Leno has led the comedian to hire Zehme to write his autobiography, which, of course, will sell gazillions, and which is due out later this year. (Working title: Leading with My Chin.) “I went to Bill because I had worked with him before,” Leno says. “At least it wasn’t another one of those ‘niceguy’ articles.”

“I’m really not interested in most people,” Zehme says, and, indeed, he rejects about half the assignments proposed to him by Esquire deputy editor David Hirshey. “The celebrity profile is the bastard stepchild of journalism, and I’m embarrassed sometimes to be associated with it. I try to do something as literary as possible. I want to do people who have lived lives. People you can learn something from as people.”

Of course, Zehme does not go through all of this hardship just to salve the angst of the baby-boomer executives who read his work. Bill Zehme believes that men are in crisis mainly because, I will submit herein, Bill Zehme is himself in crisis. And so, at age 37, he’s out to prove that there are still some bona fide Heroes left to guide him — us — through the cultural wilderness.

Crisis No. 1: His audiences with the Queen always end too soon.

Here are some things you must know to understand William Zehme, writer, rascal, raconteur. His name is pronounced ZAY-mee, although few people say it correctly (Hirshey calls him Dr. Z; Philbin calls him “Zemmy”). His parents own Clemensen’s Flowers in Flossmoor. His grandfather, as it happens, knocked ’em back regularly with David Letterman’s father (also a florist) at regional FTD meetings in the fifties and sixties. He has a sister who is 30. He is as large in demeanor as in altitude — six feet five inches — and in hair, which is thick, and carefully tended. He is divorced from his wife of four years, Tina, and he moved back to Chicago last April after a five-year stint in L.A. to be near his eight-year-old daughter Lucy, who lives with her mother in the suburbs. He is “wrecked” with love for Lucy, and calls her Queenie “instead of Princess, because she’s better than a princess,” theorizes Rhonda Hampton, a friend. “I think Lucy makes him feel safe.” He dwells in an enormous three-bedroom duplex in a converted pencil factory in Lake View, and he refers to it as “the loft that Regis built — and that Jay’s going to pay for.” In this loft is an aerie especially for Lucy’s visits; it is painted a deep purple and contains a purple neon sign that reads LUCY’S ROOM. “Only a divorced father would do this,” he says. “Every once in a while you drive your kid home and it breaks your heart.”

“He is a big fan of TV people,” Bob Sirott says. “But he is never a sycophant.”

He drinks martinis and Jack Daniel’s, rocks, water back. The same is true of Sinatra — Zehme admits to taking little pieces of the people he writes about. His pattern of speech, a sort of free-associative cadence of quirky riffs on pop culture evokes Letterman, Bill Murray, and Bill Maher — sort of like Dennis Miller, but not so mean. “It’s like one constant run-on sentence digression but every digression is pretty interesting,” says Sirott. Zehme enjoys impersonating Leno’s favorite expression with an opening whine: “Ehhhh, it’s so stupid!” He loves tchotchkes, totems, mementos. He prizes the shot glass Dean Martin employed the last time they saw each other. He spent an hour showing me the Liberace museum in Vegas and then dropped $73 in the gift shop. (Among the booty: two Liberace refrigerator magnets and a poodle-bedecked Liberace nightshirt.) We also squinted our way through the Siegfried & Roy gift shop at the Mirage around 2:30 a.m. Later, he gave me a Siegfried & Roy calendar.

Women like Zehme for many reasons, not the least of which is that he smells very nice. “My girlfriends love Bill because he has this feminine side, in a good way,” says Hampton. “He loves great smells. He has room spray in every room. There is not one bar of soap in his house that is ordinary soap; it’s all eucalyptus,” or some such tincture. He once asked Madonna, who smelled lovely herself, how Prince smelled. (Like lavender, she said.) He especially delights in the homey aroma of roasting chicken, most of all chicken Zehme, a creation of Regis Philbin’s wife, Joy (it is stuffed with oranges, and baked in rosemary and white wine). During my visits, his apartment contained several vases of fresh tulips and wildflowers. “He arranges them himself,” Hampton says. “His parents are florists.”

He will not be dissuaded from fun. He has happy feet and is famous for whirling friends around the apartment to the trains of Sinatra, no matter the hour. This past January, he tore apart his legs on a broken swimming-pool ladder in St. Barts in the French West Indies. Doctors forbade him to swim, but he gamely took to the nude beaches — bandages and all. “I’m not admitting that I was nude,” Zehme says.

He is by turns open and generous with his feelings, and protective of them. “He is very nervous about [being profiled],” says a friend. “And then, secretly, he is thrilled.” He often initiates our contacts and supplies copies of articles that embarrass him. Yet he asks me to keep mum on a few matters that might elicit a scolding from Lucy. And he tiptoes very carefully through discussions of romance in his life, assiduously discounting some friends’ suspicions that he is currently involved. “He compartmentalizes his intimacies, his confidantes,” says a long-time pal. “He tells everybody a different story.”

After his divorce he briefly dated the actress Polly Draper, starring at the time in thirtysomething, then had a relationship with Hollywood executive Tracy Barone, who produced The Money Train. He’s friends with Sandra Bernhard, Bob Sirott, painters Richard Hull and Donna Tadelman, Chicago’s Marcia Froelke Coburn, who was once his roommate, and WGN radio guy Garry Meier. He is fascinated with broadcasting, especially late-night television. “He is a big fan of TV people,” Sirott says. “But he is never a sycophant. He has this Midwestern sensibility, this sort of real-people attitude, never losing the enthusiasm. He asks the questions that those of us who aren’t jaded want to know.” (Of Sharon Stone, Zehme says, “Once, she started creeping me out, talking about her art. I thought, What happened to you? You used to be an OK broad.”) “No one has more fun being with these people, sharing the stories and hobnobbing,” Sirott adds. “But there’s no doubt that he is a tormented soul. He understands the dark side of people who are in TV and movies, that there’s something wrong with us, people who do this.”

Crisis No. 2: The world is less interesting than it once was, as are most of its inhabitants.

We’ll do the Rat Pack thing!” Zehme announces with zest, proposing that we find some loungy old Vegas juke joint in which to hang. “I think Sammy Butera’s playing the showboat.” Sadly, it turns out, he’s not. So, ’round midnight, we set out through the clanging, flashing casino at the tattered Sands Hotel, former clubhouse to Frank, Dean, and Sammy, now a bit player dwarfed by the gargantuan, Disneyesque MGM and the scary Luxor pyramid.

Like many things Bill Zehme cherishes, Las Vegas isn’t what it used to be; disturbingly, it has become a family scene. “Look at that,” he says, pointing with dismay to an ice-cream counter alongside the slots and blackjack tables. We finally belly up to a bar in Caesars Palace, next to Cleopatra’s Barge, an actual, indoor boat floating on actual water, and upon which drunken people are dancing. The seating is Naugahyde: the waitresses busty, in scanty faux-Egyptian costumes. The barge bobs more slowly as the band switches to a Burt Bacharach ballad. “Now, Burt, strange as it may sound, he was one of the greats,” Zehme pronounces. “He will be remembered!”

For Zehme, the fascination with true star quality began with Carson. As a teen growing up in suburban South Holland, he says, he was “obsessed” with Carson to the point of naming his high-school newspaper column “Monologue.” This past February he chanced to meet the retired talk-show king. “The first thing he said to me was, ‘So, has Sinatra taken a contract out on you yet?'” Zehme recalls. “And I was just thrilled that he knew who I was. He said, ‘I enjoy your stuff.’ He used to say that to comedians on the Tonight show: ‘Funny stuff! Funny stuff!”‘

Zehme drew his first journalistic sustenance from another male icon. In 1979, during his third year as a communications major at Loyola of Chicago, he offered a front-page homage to Hugh Hefner in the Loyola Phoenix. The piece drew an outraged letter to the editor signed by seven deans. This delighted not only young Zehme but also Hef, who somehow got wind of it. “The next thing I knew, I was invited to the Playmate of the Year party, every college junior’s dream.” Zehme recalls. He was joined by his photographer sidekick, Chris Pallotto, who now sells dental implants in Los Angeles. “We went out and got these stupid white suits,” Zehme says. Naturally, he wrote about that in the Phoenix, too. He also began flexing his chops on high-concept pieces: shopping Michigan Avenue with Rip Taylor, for instance. (Zehme was late, Pallotto told him later that Tayler had called him “an a.h.” Zehme’s reaction: “He called me ‘an ah’?”)

Out of school, he landed a job at a magazine for members of Montgomery Ward’s auto, health, and travel clubs, then at Success, where he established his niche with a 1982 cover story on Letterman, a newly rising star, and first made contact with Leno, Letterman’s pal. Playboy’s John Rezek gave Zehme a break, assigning him stories and celebrity Q&As, but it was Bob Greene’s assistant who vaulted him into the big time. In 1984 Tina Brown, then the editor of Vanity Fair, decided that Chicago was “fabulous,” and called Greene’s office to ask for a local writer with an interesting style. Greene wasn’t around; his aide recommended Zehme. “I became the Chicago correspondent for Vanity Fair,” Zehme recalls, which is kind of like being the Maytag repairman.” Over the next three years, Zehme says, he did “pieces on Sugar Rautbord, Linda Johnson Rice, Bonnie Swearingen, Christie Hefner, Siskel and Ebert — and that’s about all there was to do.” In time, Zehme felt his irreverent voice softening. “It’s sort of a fey beat,” he says of the Vanity Fair job. “[Brown] wanted to be loved by everyone, and with that came this sort of suck-up journalism — everybody was fabulous.” After two years of freelancing for Rolling Stone, he landed a job as senior writer there in 1989. But owner-editor Jann Wenner wanted stories about rising young stars, not the established firmament that intrigued Zehme. So Zehme told David Hirshey, “I’m not the happiest guy in the world at Rolling Stone.”

Soon he was at Esquire, where his byline has resided exclusively ever since, notwithstanding the fact that his stories are always late. “It’s like Chinese water torture for him,” says features editor Michael Solomon. Echoes Hirshey, “Bill’s pieces just sort of drip in like it’s an IV of writing. Every day you go to the fax and there’s another three paragraphs.” But they’re invariably brilliant. “He gets naked with Sharon Stone. He checks out Regis Philbin’s feet. You get the sense as a reader that you’re as close as you can be to a celebrity without being a stalker.”

Many of Zehme’s subjects have remained friendly with him: Leno, obviously; Letterman, Philbin, Stone, and Manilow (the latter “has the kind of friendship with Bill that men don’t admit to,” Hampton says). A few have not. In a 1986 Spy piece on Oprah Winfrey that Vanity Fair had rejected, he was brutal. “I used every synonym for ‘fat’ there is,” he says, now feeling quite guilty, sitting at the bar in the Mirage and whirling his Jack. He described her as “a Mississippi mud pup made good,” a loud, crass spendthrift, and quoted her saying things like “I say minks were born to die!”

Winfrey sent him a note that read only, “Dear Bill: I forgive you. Oprah.” The article was a mistake, he admits. “It’s just that she was so messianic,” he says. “She creeped me out.”

But her disappointment paled next to the wrath of David Copperfield, whom Zehme profiled in the April 1994 issue of Esquire. The story was playful, and nearly entirely positive: It called the illusionist “a presence akin to Elvis — the first pop idol of prestidigitation, and more significantly, Houdini’s only logical heir.” It did, however, describe Copperfield’s impending nuptials with Claudia Schiffer as “an accomplishment, in the minds of many, that eclipses every other feat he has managed, including escaping from a burning raft over Niagara Falls.” Copperfield was aghast, firing off a three-page letter that bitterly accused Zehme of betraying and trivializing him. “[Y]ou told me, ‘Trust me, I’m your friend, I’ll protect you,”‘ Copperfield moaned, invoking variations of the phrase seven times.

“[Zehme] was so verklempt over that,” says Hampton. “He said, ‘Oh, God, he hates me.”‘ But his response debunked Copperfield’s gripes, one by one. “You are a good, but hypersensitive man,” Zehme wrote. “If I wanted to betray you, I could have and would have, but I did not. It is not what I do.”

Says Hirshey, “That, to me, is one of the most mind-boggling responses of all time. He made David Copperfield into a kind of demigod. Certainly David Copperfield would never have been on the cover of Esquire magazine” were it not for Zehme. “He certainly will never be on the cover of Esquire again.”

“Sure, nobody likes to have their mind probed over and over again,” says Regis Philbin, who decided to do his book I’m Only One Man! with Zehme after working with him on an Esquire profile. “Zehme has a way of capturing the known and the unknown. He gets right inside people.” Philbin’s one beef: “I was the only Zehme topic that didn’t make the cover of Esquire. They had some unknown blond model: ‘Sex in America.’” For his appearance on Philbin’s show, Zehme had a mock cover printed that gave Regis his due.

Zehme has no interest in writing about Sandra Bullock (“She’s just too young to know anything”) or Conan O’Brien (“His sidekick is more interesting”).

As Hirshey puts it, “He tries to give his subjects heroic proportions, even if they’re not heroic.”

Perhaps the trickiest relationships Zehme has had to juggle are those with the dueling duo of late night, Letterman and Leno. Having been long-time acquaintances of them both, and one of the only journalists Letterman was comfortable talking to, he’s now in the uncomfortable position of being perceived as having left the Letterman camp for the Leno side. “Jay even said to me when we started the book, ‘I thought you were Dave’s guy,’” Zehme recalls. Indeed, he still admires Letterman to the point of idolatry, and identifies with the comic’s famous self-loathing. “I’ve been through enough therapy to understand,” he jokes. But the Leno book is what’s on the plate now. The manuscript is due in June.

In April, nearly finished with his search and contemplating the painful reality of facing a blank page, Zehme tells me, “I’ll become very miserable in about a week.”

Crisis No. 3: He has wandered from his responsibility to men, and he knows it.

Some people fear that lately Zehme has strayed from his quest. “All these quickie celebrity ghost jobs are taking him away from his mission in life,” complains Hirshey. “He’s had a contract for three years to write a book about Andy Kaufman,” the late genius of dark comedy. “That could be a seminal book about comedy culture for the last 20 years, and one that I think most people would love to read.” Indeed, Zehme admits, in his study are several boxes of Kaufman’s personal effects: stories, letters, scripts. “I wonder about that book, too,” he says, and promises he’ll finish it by the end of next year. Of his recent celebrity book ventures, he says, “I never thought I would do this. Regis approached me — I had never made that much money in one piece. I’ve worked so long to have a voice of my own that it’s strange for me to become a channeler of somebody else’s voice.”

Still, he argues, the books have been good. He’s excited about the Leno tome. Even closer to his heart: a proposed book to follow up the Sinatra Q&A — a man’s guide to life to be called What Would Frank Do? And he will resume his regular salvos in Esquire, which of course will not feature the likes of Sandra Bullock (“She’s just too young to know anything”) or Conan O’Brien (“His sidekick is more interesting”). “It’s a sad thing, the state of fame today,” Zehme says. “I mean, Brad Pitt? Truculent young actor? I can’t get interested in that.” Sean Connery’s more like it. Mickey Rooney. You get the picture.

Then, somewhere in the misty future, there is the Holy Grail, the profile to end all profiles, the fin de siècle interview, within which surely lies the answer.

Johnny.

“Now, that would be the ultimate story,” Zehme says. When he met Carson, he amused his hero with a reference to the actor who played him in The Late Shift, an HBO movie about the Leno-Letterman battle for the Tonight show. “I said, ‘You don’t look anything like Rich Little.’” In April he squired Carson’s office assistants, “the women of Carson,” to lunch in Santa Monica for some schmoozing, only to bump into the King again. “I trust you’re going Dutch,” Carson joked. “These women are handsomely paid.”

And so, Zehme has started tiptoeing up the mountain toward the great Carnac, the once and forever éminence grise of late night, a man among men whose lofty confines no journalist-seeker has breached since his abdication of the latenight throne. He has thus far decided it is not prudent to ask. Not just yet.