A swimmer who became Tarzan. A sprinter who became a congressman. Another sprinter who broke her leg in a plane crash after winning a gold medal, then recovered to win another gold, eight years after the first. The Chicago area has produced some of the most colorful and accomplished athletes in the history of the Games. Here’s our list of Chicago’s Greatest Olympians.

Frank Foss, track and field: Foss set a world record in the pole vault at the 1920 Antwerp games: 13 feet 5 inches. Foss vaulted with a bamboo pole, which was more flexible than ash and hickory, from which poles were constructed in the 19th century. The big revolution in pole technology occurred in the 1950s, when fiberglass poles enabled vaulters to fling themselves to greater and greater heights. The current world record, set last year by Sweden’s Armand Duplantis, is 20 feet 3-¼ inches.

Johnny Weissmuller, swimming: Weissmuller isn’t just the most famous Chicago Olympian; he may have had the most star power of any Olympian in history. As a boy, Weissmuller, an Austro-Hungarian immigrant from what is now Romania, learned to swim in Lake Michigan, then joined the Illinois Athletic Club, which had already produced several Olympians. According to a club history, Weissmuller “was a high school drop-out, who probably never spent more than a year at his school, Lane Tech, and never swam on its championship swim team. He was basically a beach bum, who hung out at the Fullerton Avenue beach. What early formal swimming training he picked up was at the Stanton Park Pool at the Larrabee YMCA.”

The IAC’s coach, William Bachrach, turned the beach bum into the greatest swimmer of the first half of the 20th century. As an amateur, Weissmuller never lost a race. He won five gold medals: in the 100-meter freestyle, 400-meter freestyle, and 4×200-meter freestyle at the 1924 Paris Games, and the 100-meter freestyle and 4×200-meter freestyle at the 1928 Amsterdam Games.

It was Weissmuller’s good fortune that his swimming career ended just as the era of Hollywood’s sound pictures was beginning. In 1931, he was working out at the Hollywood Athletic Club — to keep fit for his post-Olympic gig as a BVD swimsuit model — when he was approached by Cyril Hume, a scriptwriter for MGM.

“Hume went on to explain that the studio had assigned him to create a script for a new film, Tarzan the Ape Man,” according to Michael K. Bohn’s Heroes & Ballyhoo: How the Golden Age of the 1920s Transformed American Sports, by Michael K. Bohn. “He described the producer’s criteria for the Tarzan role—‘young, strong, well-built and reasonably attractive.’ The ability to appear comfortable in a loin-cloth was also important.” (Weissmuller arguably owed his shapely figure, to some extent, to a vegetarian diet picked up from John Harvey Kellogg at Kellogg’s famous Michigan sanatorium.)

That was more important than the ability to act, since Tarzan’s dialogue was rarely more complicated than “Jane, Tarzan, Jane, Tarzan.” Weissmuller described the work as “like stealing money. There was swimming in it, and I didn’t have much to say. How can a guy climb trees, say ‘me Tarzan, you Jane’ and make a million?”

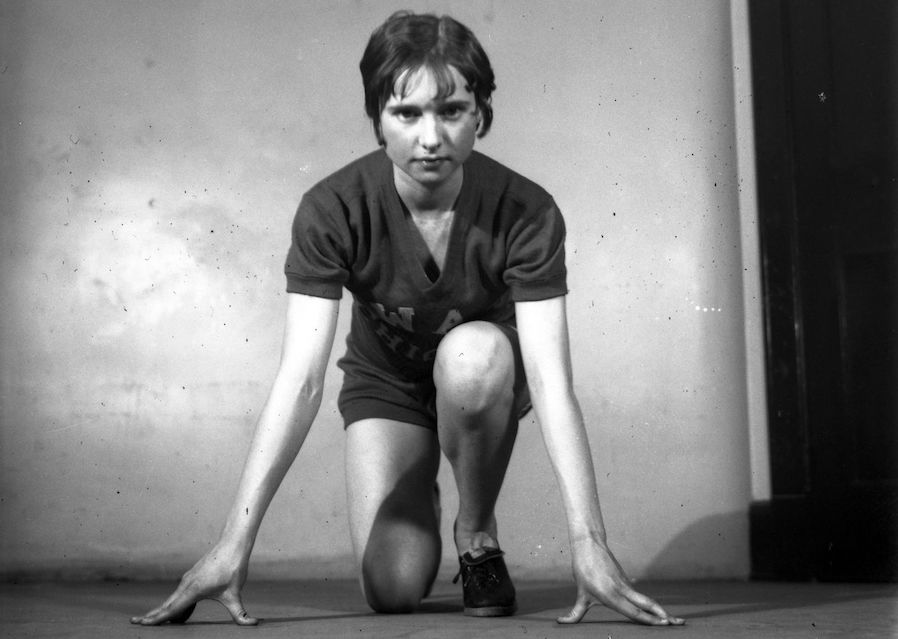

Betty Robinson, track and field: One day in April 1928, Betty Robinson was late for school at Thornton Township High. She sprinted to catch a train that would take her from her home in Riverdale to Harvey. Thornton Township’s track coach happened to be a passenger. Impressed with Robinson’s speed, he invited her to try out for the team.

Robinson trained with the boys and beat them. Later that spring, running for the Illinois Women’s Athletic Club, she tied the 100-meter world record at a track meet in Soldier Field. Then she finished second at the Olympic Trials in Newark. And so, barely three months after she’d been discovered chasing a train, 16-year-old Betty Robinson was on a ship bound for Amsterdam, where she won the gold medal in the 100 meters in the first Olympics in which women could compete in track and field. (You can watch the race here.)

Her next achievement was even more remarkable. In 1931, Robinson climbed into her cousin’s biplane for a pleasure flight over the south suburbs. The plane crashed. According to the book Fire on the Track: Betty Robinson and the Triumph of the Early Olympic Women, rescuers saw that Robinson “had suffered at the very least a broken leg, judging by the bone poking out, [and] appeared to be dead.” Robinson survived the crash, but “her chances of running again were highly improbable, given that the injured leg would likely remain shorter than the other one…. Her thighbone had fractured in numerous places, and a number of silver pins had been inserted.”

Robinson wouldn’t run again for two and a half years. Eventually, she regained her old speed, but there was still a barrier to resuming her track career: the pins in Robinson’s leg made it impossible for her to crouch into a four-point starting position. So at the Berlin Games, she ran the third leg of the 4×100 relay, winning a gold medal after the German team dropped the baton on the final pass.

Ralph Metcalfe, track and field: The Tilden Tech graduate was the silver medalist in the 100 meters at the 1932 Los Angeles Games and the 1936 Berlin Games, when he lost to Jesse Owens. Metcalfe did win a gold medal in Berlin as a member of the integrated 4×100-meter relay team—to the displeasure of Hitler, whose all-Aryan squad had to settle for bronze.

After the Olympics, though, Metcalfe led a much more successful life than Owens, perhaps because silver medalists aren’t defined by their athletic achievements. While Owens raced horses for money and went bankrupt as a dry cleaner, Metcalfe built a career in academia and politics. He was elected alderman of the Third Ward in 1955, and succeeded William Dawson as congressman for the historically Black 1st District in 1970. On the City Council, Metcalfe was a member of the “Silent Six”—Black aldermen who faithfully followed Mayor Richard J. Daley’s Machine line, in spite of Daley’s lack of interest in the well-being of their South Side constituents. As a congressman, though, Metcalfe defied the mayor, refusing to support the re-election of State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan, who had ordered the raid that killed Illinois Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton. (“It’s never too late to be black,” Metcalfe said.) Metcalfe also co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus.

Adolph Kiefer, swimming: “I learned to swim in Lake Michigan—my father took us swimming at Wilson Avenue beach every Sunday after church,” Adolph Kiefer once recalled. “I started when I was about nine or ten years old. We enjoyed it because we’d get an ice cream cone on the way home—black walnut ice cream.” He soon became such a fanatic that when his family vacationed at a resort in Michigan he swam all the way across a lake and back, a mile each way.

Kiefer’s father, a German-born candy maker, died when Kiefer was only 12, but before he passed away he told his son that he was going to be “the best swimmer in the world.”

Kiefer worked furiously to achieve the destiny his father had forecast. He swam six days a week in pools near his home in Albany Park, then on Sundays he rode his bike, sneaked onto streetcars, or hopped onto trucks to get to the Jewish Community Center on the near south side, which had the only pool open that day. In high school, Kiefer lied about his address so he could go to Roosevelt, which had the best pool.

Although swimming historians disagree, Kiefer claimed to have invented the modern backstroke; according to an official from the International Swimming Hall of Fame, two swimmers were using a high-riding backstroke before Kiefer, but Kiefer mastered the style. “He was the king. He just had tremendous power. His strength overcame any technical flaw. His technique was not unique, but he perfected it.”

At the 1936 Olympic trials Kiefer broke the world record in the 100-meter backstroke three times. He was only a junior in high school when he sailed for the games in Berlin, but he was already recognized as one of the great swimmers of his generation, part of a U.S. swim team so talented even Hitler wanted to meet them. He showed up at a training session with filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. “He was there with his cronies,” Kiefer said. “He was a little guy with a little mustache, with a hat over his head, and three or four of us shook his hand. Actually what I should have done is throw him in the pool! At my age, which was young, I didn’t realize the atrocities or the problems which were existing then.”

Kiefer won the 100-meter backstroke in 1:05.9, demolishing the eight-year-old Olympic record by 2.3 seconds. The 1940 and 1944 Olympics were canceled due to World War II, so he joined the Navy and developed a swim training program to prevent sailors from drowning. After the war, the strikingly handsome Kiefer turned down Hollywood’s offer to become the next Johnny Weissmuller—as a family man, he didn’t want to romance starlets onscreen—and instead founded a swimming supply company which introduced the first nylon bathing suits. It’s still doing business in Bloomington.

Terry McCann, wrestling: At Schurz High School, Terry McCann was the 1952 Illinois State Champion in the 112-pound division. At the University of Iowa, McCann was an NCAA champion at 115 pounds. Then, as a 26-year-old father of five with a full-time job as a production manager for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Tulsa, Oklahoma, he made the Olympic team.

“No 1960 Olympian earned his place on the Big Team harder than this 5 foot 4 inch, 125 pound blond alumnus of Schurz High School,” the Tribune reported in an article on McCann’s return to Chicago, where his children stayed with their grandparents during the Olympics. “Last April, McCann underwent a second operation for torn knee cartilage in Tulsa, Okla., his home for the last three years. Thus, he was unable to take part in the regular Olympic tryouts a week later in Ames, Ia. Thru unprecedented action by the American Olympic committee, he was permitted to come to the Olympic training camp in Norman and try his grip against other wrestlers of his weight. Terry finally pinned the No. 1 man, Dave Auble of Cornell university, twice.”

In Rome, McCann only lost a single match on his way to winning gold in the bantamweight division, making him Illinois’s only wrestling gold medalist. McCann retired from competition after the Olympics, but went on to help found USA Wrestling, the sport’s governing body, and served as the executive director of Toastmasters for three decades.

Bart Conner, gymnastics: The 1984 Los Angeles Olympics were the most red-white-and-blue display of Americanism ever seen on television. That year was the peak of Reagan-era Cold War patriotism. Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A. was the #1 album. Team USA won 83 gold medals, the most by any country in any Olympics — because the Soviets and their Eastern Bloc allies didn’t show up, as retaliation for our boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics. Two of those gold medals were won by the most all-American Olympian of all time: blond Bart Conner, who got his start on a playground in Morton Grove.

“I would play in Austin Park when I was little, and from a very early age I was able to do a handstand on the monkey bars,” Conner once told the Niles West News, his alma mater’s school newspaper. “My parents realized my talent and I just went from there.”

Conner won a gold medal in the team competition, and as an individual in parallel bars. In 1996, Conner won an even bigger gymnastics prize: he married Romanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci—the first gymnast to score a perfect 10.0 at the Olympics, which she followed with six more en route to dominating the 1976 Games. The couple live in Norman, Oklahoma, where Conner operates the Bart Conner Gymnastics Academy.