So I think we can safely say the Bears' season is over:

- Jay Cutler (thumb)

- Matt Forte (knee)

- Johnny Knox (back)

- Gabe Carimi (IR)

- Sam Hurd (DEA)

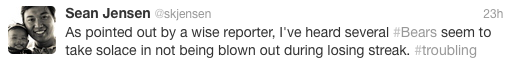

That's the starting QB, the starting running back, the number-one wide receiver, a future-star tackle, and the special-teams captain. The Bears seem to agree, Sean Jensen and Jon Greenberg report:

I don't know if I'm troubled by it; much as we like to attribute a militaristic do-or-die attitude to athletes, they're also rational people, and the Bears' defense has to realize on some level that good solid stops are likely to turn into pyrrhic victories. To add insult to injury, the decimated team stumbles into a showdown against their hated rivals—whose perfect season was just ended thanks to a great game by Kyle Orton.

It reminds me a bit of my fantasy football team. I drafted Peyton Manning, Matt Forte, and Adrian Peterson—which meant, during the drive to the fake playoffs, I was starting Tim Tebow, Toby Gerhart, and Dexter McCluster (not actually a running back) in the three most important slots. I have atrocious luck in fantasy football, having picked Daunte Culpepper the year he instantly stopped being a good quarterback, and Tom Brady the year he lasted five minutes. Looking at the wreckage of the Bears' season, I empathize.

Fantasy sports are one of the most preposterously silly things one can do with one's time, but they've made me a calmer, more rational sports fan. For instance, I've been playing Out of the Park Baseball, the computer game I recommend if you want your kid to grow up to be the next Theo Epstein: a stat-based computer baseball sim, like digital strat-o-matic or SimCity for baseball nerds. The free version starts you in the 2007 season, so I tried to remake Cubs history—and failed, three times, to get the team above .500 in three seasons.

(I'd forgotten that the Cubs paid Jason Marquis a combined $11 million dollars in 2007 and 2008, signing him as a free agent the year after he'd put up a 6.02 ERA for their rivals, leading the league in earned-runs and home runs against. They were right that Marquis would improve—he had a 4.60 ERA in 2007. OOTP saddles you with all the bad contracts you know and love, and the "fun" part is getting out of them.)

I was thinking about this while reading Michael Miner's post about coming to terms with Albert Pujols leaving his beloved Cardinals, and how that compares with the glorious past of Stan Musial in the reserve clause days. Some of that has to do with the defeat of the reserve clause, about which the best thing I can recommend is the outstanding history A Well-Paid Slave, and how free agency has changed the way we relate to players.

But some of it, I can't help but think, has to do with the rise of fantasy sports and the way sophisticated statistical analysis has creeped into our appreciation of the games we love. When I was younger, I would have looked at Pujols and thought of two World Series titles, his brutally, beautifully efficient swing, the cold elegance of his moon-shot destruction of Brad Lidge, and his catlike presence at first base. I haven't forgotten any of that, but it's tempered with things like WAR: can you replace Pujols? Yes, with math. It's tempered by the knowledge of what happens to players of Pujols's age and caliber. It's tempered by an understanding of market disparities and how massive contracts play out over time.

Just the other day I watched a movie starring two of the most sought-after actors in Hollywood, who spent most of the film looking at spreadsheets and explaining how math can improve the performance of sub-star athletes and aging veterans. Moneyball was the moment this broke into the popular consciousness, but it was paralleled by a rise in statistical games about sports, themselves feeding off the great advancements made in our understanding of the science and economics of athletics. The second-biggest name in Chicago sports, after Derrick Rose—whom we almost lost for the season due to a labor dispute—is Theo Epstein, the Cubs' young baseball savant.

It's an Enlightenment age in sports, as the devout belief in its saints gives way to a million amateur number-crunchers, just as similar philosophical and scientific shocks created gentleman astrophysicists and naturalists in their wake. It's a less romantic, more rational sporting world, but I don't find that I'm less empathetic for it. Quite the opposite.

Photograph: Chicago Tribune