While reading up for my 12 Months, 12 Photos, 12 Stories series, I noticed a theme reoccuring in things I'd read or written about last year. Then, as I was brainstorming, I read this:

One of my good and dear friends is about to be discharged with 100% disability from the Army. At 32 years old, he can’t remember what day it is, and sometimes he can’t remember if he’s back here in the states, or in Germany, or in Afghanistan where he got hurt.

Traumatic Brain Injury is the signature wound of these current wars. Gerald, who is one of the smartest people I know, just chatted with me on Facebook and couldn’t remember that I was retired, or that one of the last official acts I carried out was pinning his Sergeant’s stripes on him. Because he couldn’t remember being a Sergeant, unless he sees the rank on his chest.His wife, Lisa tells me that he occasionally can’t remember her name. “I can see that he knows I’m important to him, but he struggles with that sometimes.”

That came immediately on the heels of John Keilman's heartbreaking piece about Anthony Wagner in the Tribune:

As a vital link between the Green Zone and Baghdad International Airport, Route Irish was the scene of frequent IED attacks and suicide bombings. Not long after he arrived, Wagner said, he was pulling guard duty in a tower overlooking the road when someone fired a rocket at him. It missed, but the noise of the detonation echoed in his skull for hours.

That was the first of five episodes in which Wagner said he was caught in the shock wave of an explosion. The most serious came when an IED went off near his armored vehicle. The blast pitched him around the troop compartment like a toy, and he felt the tremors through his entire body. That night, he suffered a splitting headache, disorientation and dizziness, almost as though he were drunk.

Looking back, he said, he was probably suffering from one of several concussions that, years later, would lead him to get treatment for a mild brain injury. But he never told the medics. When other soldiers were dying, seeking treatment for a headache was unthinkable.

In the comments following that first post, others relate their stories of friends and fellow veterans who suffer from brain injuries and/or post-traumatic stress disorder in the wake of their service in Iraq or Afghanistan. The numbers are jaw-dropping:

Officially, military figures say about 115,000 troops have suffered mild traumatic brain injuries since the wars began. But top Army officials acknowledged in interviews that those statistics likely understate the true toll. Tens of thousands of troops with such wounds have gone uncounted, according to unpublished military research obtained by ProPublica and NPR.

The phrase "mild traumatic brain injuries" understates the severity of the injuries. As ProPublica's T. Christian Miller and NPR's Daniel Zwerdling point out—in the first piece in a two-year investigation of war-related brain injuries, "mild" can be anything up to an injury that leaves the victim unconscious for less than half an hour. But we know, or ar at least starting to learn, that multiple mild brain injuries—concussions, basically—can lead to long-term brain damage. We know, in part, because of football. Recall the suicide of former Bears great Dave Duerson, who shot himself in the chest earlier this year after leaving instructions that his brain should be studied for permanent injury:

Before shooting himself in the heart in February at age 50, Duerson expressed the wish that his brain be studied for signs of disease. On Monday, scientists at Boston University who examined Duerson's brain tissue said he suffered from a "moderately advanced" case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease associated with repeated blows to the head.

His brain showed pronounced changes in the frontal cortex amygdala and the hippocampus, which control judgment, inhibition, impulse, mood control and memory, said Dr. Ann McKee, a co-director of the Center for Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at the Boston University School of Medicine and director of the Bedford VA CSTE Brain Bank.

Evidence that Duerson's CTE affected his judgement, mood control, and memory can be seen in the decline that led to his suicide:

Sitting on the disability panel, he was well acquainted with the dementia and depression associated with years of hard hits. The study of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) was relatively new, but there were already horror stories involving the spiraling lives and suicides of former players who had tested positive for the syndrome in postmortem brain exams. Mike Webster lived in his pickup truck. Terry Long chugged antifreeze. Andre Waters shot himself in the head. Justin Strzelczyk smashed head-on into a truck during a 90-mph police chase. Tom McHale overdosed on pills.

[snip]

According to Henry and Yvette, Dave's mind was already slipping when he opened his new company. Always patient and pragmatic, he became prone to viciousness and tantrums. Even his speech and mannerisms changed. "Suddenly every word was an expletive," Henry says. "He was always agitated and fidgety."

His business discretion suffered. He sank a million dollars from his personal bank account, Henry says, into keeping the fledgling factory afloat. Violating his own business plan, he rushed his celebrity-branded DD sausages onto the market. "We were hemorrhaging money on retail," Henry says. "The little money that came in went to keeping people paid."

One of the problems with CTE is that its mental symptoms can be difficult to separate from run-of-the-mill behavior. Lots of people are bad businessmen. Lots of people are angry and agitated. All that can be seen is changes in behavioral patterns—which makes diagnosing head trauma in military veterans, returning from the horrors of war, particularly difficult to diagnose:

The interplay of TBI and mental health problems, particularly PTSD, has become a vexing issue for the military. Jordan Grafman, a senior investigator at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and member of the Dana Alliance for Brain Initiatives (DABI), has been studying the links in brain-injured Vietnam veterans. He says, “The question is: does somebody simply have PTSD, or have they been exposed to a minor head injury? The diagnosis is difficult because similar deficits may be seen in both cases. How do you tease that apart? It’s also complicated by the fact that we don’t know what the risk factors are for getting a mild head injury if you’ve been exposed to a blast.”

Football and war have long run on parallel tracks in the public imagination, in part because of their structure, in part because of their violence. In the year to come, the two will become more inextricably linked, as data continues to pour in from the armed forces and a lawsuit on behalf of 21 former NFL players, filed at the end of 2011, advances in court. Ideas to reduce or repair brain trauma are also floating around, from simple solutions like customized mouthguards to a DARPA-funded study on brain replacement parts. But we're still operating on unknowns:

“Concussions are indeed a mystery,” says Hunt Batjer, chairman of the department of neurological surgery at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and cochair of the National Football League’s medical committee for head, neck, and spine injuries. “There are a thousand things we don’t know.” Among them: “How can a condition that presents clinical symptoms that are unassociated with obvious structural changes ultimately lead to permanent neurological damage?”

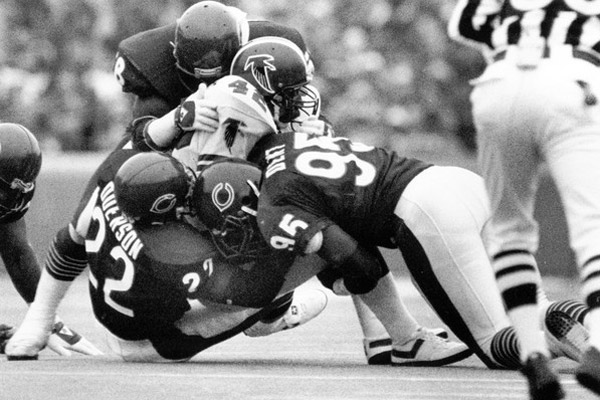

Photograph: Chicago Tribune