Occupy Wall Street is Time's story of the year; make of that what you will, but it's a fair indication that the movement and its inspirations and complaints have reached saturation point. Not making as many headlines has been the still small voice of the extremely wealthy. The 99 Percent has a blog; the 53 Percent has a blog; what of the One Percent?

I'm only sort of being snide. Occasionally a rich guy will pop off, and it makes the news. But we don't have much broad, systematic information on the sociopolitical beliefs of the rich. We can try to divine them from political contributions, but even big money won't buy you a diverse buffet of options; a few heretofore futile runs at a centrist third party aside, big-money donors still have to cope with the same two-party system as the rest of us. Fortunately, the Russell Sage Foundation hooked up with NORC and three Northwesterners, led by Benjamin I. Page (Gordon S. Fulcher Professor of Decision Making) on the working paper "Wealthy Americans, Philanthropy, and the Common Good," a survey whose 104 Chicago-area respondents—a small sample size, granted, but the one percent is by definition small—fall mostly in the famous, mysterious not-99 percent, with an average wealth of $14 million and a median of $7.5 million.

Turns out they're just like us. Kind of.

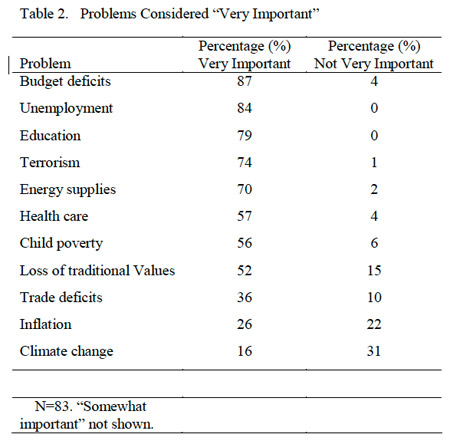

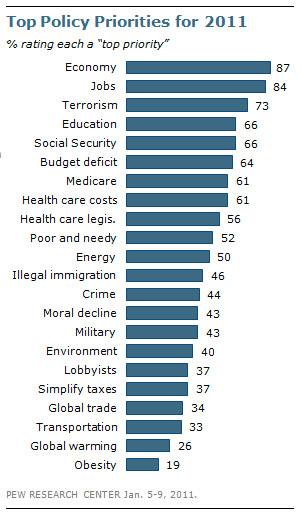

If you compare this to a Pew poll earlier this year about policy priorities, not so much an apples-to-oranges comparison as an oranges-to-tangelos comparison, the results are somewhat similar.

The ordering is pretty similar. The wealthy are more conservative—58 percent Republican, 27 Democrat—but not a great deal more. They're much more concerned about budget deficits than the public at large, but the two polls are identical on employment. They're less concerned about health care, less concerned about global warming, more concerned about "moral decline," but not by a great deal. Concerns about terrorism are equally high. Pew didn't poll on inflation, but the wealthy are seemingly unconcerned—perhaps because it doesn't have the same effect on your savings, retirement, and buying power, but it still runs counter to the Fed's ongoing focus.

One thing that jumps out is the higher emphasis on education, an aspect of public policy that's been en vogue among the wealthy as of late.

But drilling down, the philosophical differences are more substantial:

An important theme that emerges from the answers to many of our survey questions is that our wealthy respondents, when they focus on exactly how to advance the common good, often tend to think in terms of “getting government out of the way” and relying on free markets or private philanthropy to produce good outcomes. Evidence from identical questions asked in various surveys of the general public indicates that in this respect the wealthy tend to differ markedly from less affluent citizens.

[snip]

Of those respondents who considered deficits the most important problem, most wanted to address them by cutting spending rather than increasing revenue. None at all referred only to raising revenue. Two thirds (65%) mentioned only cutting spending, while 35% mentioned both spending cuts and revenue increases. Their comments mentioned “reduction across the board in order to put the house in order”; “reduce

government spending first and foremost”; “solve the expense of transfer programs, i.e. Social Security and Medicare. We cannot afford to keep funding these programs”; “major cutbacks in spending”; “lots of fiscal restraint…re-structuring many entitlement programs, means-testing Social Security and Medicare.”

[snip]

Most of our wealthy respondents tilted toward cutting back, rather than expanding, most federal government programs (nine of the twelve we asked about), including popular entitlements like Social Security and health care. There was little sentiment for substantial tax increases on the wealthy or on anyone else.

This extends to employment:

Responding to specific policy preference questions, most of our wealthy interviewees opposed the idea that the government in Washington should “see to it” that anyone able to work can find a job. They overwhelmingly opposed the idea that government should “provide” jobs if private enterprise cannot. There was very little support for generous unemployment insurance or for expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for low-wage workers.

The wealthy are somewhat more willing to devote government resources to education:

Our wealthy respondents tilted toward “expand[ing]” rather than “cut[ing] back” federal aid to education, and a majority expressed willingness to pay “more taxes” for early childhood education in kindergarten and nursery school. Yet only a minority (about one third) agreed with the proposition that “the federal government should spend whatever is necessary to ensure that all children have really good public schools they can go to"…. Only about one quarter of our respondents agreed that “the federal government should make sure that everyone who wants to go to college can do so,” and only a third said that “the federal government should invest more in worker retraining and education to help workers adapt to changes in the economy.” All in all, wealthy Americans apparently do not favor large new investments of public money to improve the quality of education or access to education in the United States.

But they still prefer that money be integrated with the free market:

Instead, our respondents favor market-oriented reforms. A majority favor parents getting tax-funded vouchers to help pay for their children to attend private or religious schools instead of public schools. A very large majority (93%) favor the idea of charter schools, “operating under a charter or contract that frees them from many of the state regulations imposed on public schools and permits them to operate independently.” A similarly overwhelming majority favor merit pay for teachers.

Evaluating motives as selfish or beneficent is a difficult political and philosophical challenge (the "what's good for GM is good for America" dilemma), much less coding it for the purposes of an academic paper, and you could conclude from the above that the wealthy are supremely self-interested. But that's not the conclusion the authors came to:

This is not to say that all our respondents were correct about what would benefit their fellow citizens. We cannot be sure of that. But our evidence indicates that when wealthy Americans contact high-level public officials, they often address the common good as they see it, not just their own parochial concerns.

A great deal is made about how the wealthy are able to advance their motives, self-interested or not, by bringing their considerable resources to bear on politicians and issue-oriented organizations. But the wealthy don't just have more leverage; they're also more politically active, aware, and persistent:

Wealthy Americans tend to be very active in politics, far more so than their less affluent fellow citizens. As Table 3 shows, nearly all our respondents say they voted in the 2008 presidential election. A very large majority say they pay attention to politics “most of the time,” and the average (median) respondent says that he or she talks about politics five days of the week. (Several commented, “all the time!”) Their attendance at a campaign speech or meeting (41%), and the frequency with which they have contributed money to a political party or candidate or other political cause in the last three or four years (68%), are much higher than among the general public.

Of course, one thing outside the authors' scope is how barriers to entry correlate with political activism:

Most of our respondents supplied the title or position of the federal government official with whom they had their most important recent contact. Several offered the officials’ names, occasionally indicating that they were on a first-name basis with “Rahm” Emmanuel [sic] (then President Obama’s Chief of Staff) or “David” Axelrod (his chief political counsel.)

Photograph: John Picken (CC by 2.0)

Comments are closed.