I woke up this morning to hear Eric Klinenberg (a Chicago native whose breakthrough work, Heat Wave, was about the deadly 1995 heat wave) discussing social cohesion and efficacy (the cornerstone of Robert Sampson's recent Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect) on NPR. It was pretty exciting, if you're into that sort of thing. Klinenberg was discussing Hurricane Sandy and "climate-proofing" cities (he has a new piece about it in the New Yorker), but he was drawing on his own work on Chicago, in ways that are constructive beyond climate.

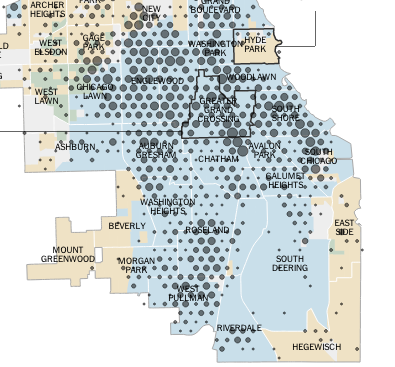

Then I got to work and saw that the New York Times ran an excellent map on 12 years of homicides in Chicago versus income, education, and race, following up on Chicago's jump in homicides in 2012; it's worth a look, especially if you've been following, say, Steve Bogira's consistent writing on the links between crime, poverty, segregation, and public health in Chicago. There's a relationship there, that social efficacy—social organizations, businesses, nonprofits—runs through.

Let's start with a section of the NYT map. The bubbles represent 30 homicides, 10 homicides, and 1 homicide, respectively. Blue areas are black majority; green, Latino; and tan, white.

As you can see, Englewood and Greater Grand Crossing have a high intensity of homicides, as does South Shore, and parts of other neighborhoods. But as you move south of Englewood, the intensity drops off noticably (South Deering is misleading; very little of it is residential and most of it is lake and golf course, and Riverdale is mostly non-residential, except for the part where there are homicides). In particular, much of Chatham and Avalon Park, the northern part of Roseland, and parts of Auburn Gresham, Calumet Heights, and Washington Heights, don't have the same uniformity of fatal violence that you see in Englewood or GGC.

And Klinenberg and Sampson have done extensive research into these communities. Here's Sampson, in Great American City:

Why does violence unhinge some communities and draw others together? Among the 25 predominantly black communities in Chicago (defined as 75 percent or more black), Avalon Park and Chatham rank first and second, respectively, in terms of the level of collective efficacy as independently measured in the PHDCN [Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods] surveys. In terms of organizational participation, I consulted both the nonprofit data and the PHDCN. Although they are in the middle of the pack in terms of official density of nonprofits, averaged across the two waves of the survey, Avalon Park ranks fifth or on the top fifth percentile of organizational participation in the entire city, and it is second among black communities and Chatham is eighth. This performance is notable because neither community boasts a University of Chicago or anything like it in terms of organizational heavyweights. The evidence, then, indicates that there is a relatively strong pool of organizational activity and latent capacity for collective efficacy in these communities, leading me to be optimistic concerning their struggle to remain vibrant.

Roseland, Sampson notes, is poorer than Avalon Park and Chatham and "showing signs of distress," but "the participation rate by residents is surprisingly high, given its profile of concentrated poverty…. Among predominantly black communities, it ranks in the upper quintile in collective efficacy as well as organizational participation, and in the upper third of collective action events."

(One interesting finding from Sampson's work: church density is "negatively related to collective efficacy." Fuller Park, one of the worst neighborhoods in the city by almost every metric, has the highest concentration of churches per 100,000 residents and the second lowest trust in neighbors. Whether that's cause or effect is another question.)

Auburn Gresham has substantial problems with crime, but in the case of the 1995 heat wave, it fared much better than Englewood, just to the north. Klinenberg, in his New Yorker article, writes:

The key difference between neighborhoods like Auburn Gresham and others that are demographically similar turned out to be the sidewalks, stores, restaurants, and community organizations that bring people into contact with friends and neighbors. The people of Englewood were vulnerable not just because they were black and poor but also because their community had been abandoned. Between 1960 and 1990, Englewood lost fifty per cent of its residents and most of its commercial outlets, as well as its social cohesion…. Auburn Gresham, by contrast, experienced no population loss during that period.

This reminds me of something I came across when writing "Chicago's Poor Neighborhoods: Everything Deserts," an observation about Harlem versus Chicago by Mario Luis Small that I also had, in reverse, when I first saw Harlem a couple years ago:

One of the first things you notice when ascending from the A train subway stop at 125th Street in Harlem, where I lived while conducting five years of research in New York City, is the density. It is a density of both people and organizations, as just about every lot on either side of the street is occupied by a clothing store, bank, pharmacy, grocery store, electronics outfit, beauty salon, or restaurant (such as the legendary Manna’s), and every conceivable space on either sidewalk is filled with old and young, mostly African American men, women, and children struggling to get past the crowds (see Newman 1999). It was a marked contrast to many wealthier neighborhoods in the city, where the streets were often desolate and all but a few specialty establishments were difficult to locate.

[snip]

I thought of both neighborhoods when, soon after recently moving to Chicago, I spent hours walking block upon block of its South Side neighborhood, including 63rd Street, the area a few blocks south of the University of Chicago…. What I first noticed, and what took me months to get used to, was the utter lack of density, the surprising preponderance of empty spaces, vacant lots, and desolate streets, even as late as 2006. Repeatedly, I asked myself, where is everyone?

I used to live at 62nd and Woodlawn, just south of the U. of C., and took the 63rd Street bus most days. To the east there are some handsome new townhouses where the Green Line used to be, a massive church, and a struggling commercial strip; to the west there's the famous Daley's Restaurant, a small grocer, a couple run-down stores, and lots of empty space, especially once you get west of Cottage Grove. Passing by the other day, I saw that the coffee shop at the corner of 63rd and Woodlawn was still there after a couple years, and was legitimately excited to see it's survived so far. That post has a lot more about the odd—in contrast to other cities—lack of commercial density in Chicago's poor neighborhoods. By the numbers, it's pretty striking.

All of this is a roundabout way of saying: poverty, race, and geography are all closely related to crime, but there are differences within that geography, which Sampson and other new Chicago School sociologists are working to get to the bottom of. And it's related to Garry McCarthy's approach to crime, which is influenced by the sociologist Tracey Meares, formerly of the University of Chicago:

Before any real progress on crime can be made, police-civilian relations must improve. McCarthy says he has been particularly influenced in recent years by the work of Tom Tyler, a psychologist at NYU, and Tracey Meares, a law professor at Yale. “It turns out that the reason people comply with the law isn’t because they’re afraid of going to jail,” he says. “A large body of evidence shows that people comply with the law because of police legitimacy.”

McCarthy’s strategy for improving that legitimacy can make him sound like a social worker. He favors the establishment of “catchment centers,” in churches and nonprofit offices, where police can bring kids picked up after curfew. “So if we bring in Little Johnny, [a social-service provider] can say, ‘Why aren’t you at home? Did you eat today? Who do you live with? Mom and Dad? Grandma? Great-Grandma?’”

It's not just a matter of making sure Little Johnny ate today; it's also a matter of building sufficient trust with the police so that shooting victims are willing to cooperate with the law, a huge roadblock to enforcement within the city.

Working with the police, working together within the community to reduce crime, rather than shield the men who commit it, is a critical form of social efficacy and cohesion. And it raises a lot of questions, ones that will remain as long as homicide levels stay high: Does the CPD have that capability? What city departments have the capability of addressing problems of community efficacy, from public health to education to commerce? Do we even have a framework for that? If homicides don't decline in 2013, how much time will McCarthy be given to implement his approach?

Photograph: Chicago Tribune