So: Illinois has a brand-new pension plan. Who says Squeezy doesn't get results? News broke about it last night, and it got announced at a press conference this morning. It's big news in the sense that Elaine Nekritz, who is co-sponsoring the bill with Daniel Biss, says that she has, 21 co-sponsors from both parties (the pension debate has been a bit more bipartisan than you might think; the bills backed by Michael Madigan and Tom Cross have more similarities than differences, though the differences are substantial).

What's in it is both big news and not. It's a synthesis of a lot of the things that have been floating around, with some new approaches. For instance:

"Creating a new 30-year pension payment plan, making the state pay its employer share with a new funding right that can be enforced through court action" and "Further paying down pension debt with revenues freed ups when existing pension obligation notes are paid off."

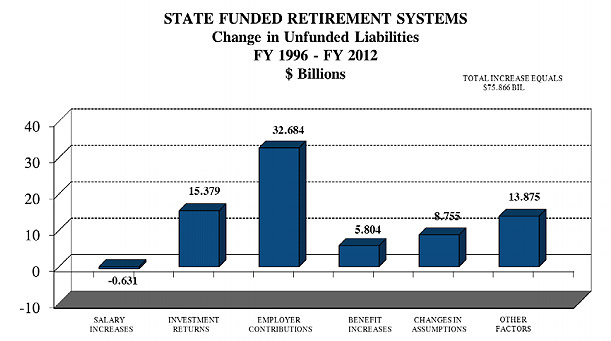

These are both straight out of Rep. Mike Fortner's playbook. The first basically says that if the state doesn't pay what it owes into the pension funds, it can be sued for doing so. This is significant because the main driver of the state's unfunded liabilities has been the state's unwillingness to make the requisite payments into the system (PDF), even more than investment losses.

The second is the cornerstone of Fortner's proposal, HB6204:

Fortner said that the current fiscal year calls for a $3.6 billion transfer payment — coming from the state’s general fund — to help move the system toward being 90 percent funded by 2045.

Fiscal year 2014 sees that amount increase to $3.8 million.

Fortner would reduce that by taking the same amount currently made to retire state bonds maturing in 2015, 2019 and 2033 and putting the outlay toward fully funding the system.

So it's not a new revenue stream per se—it's revenue freed up by the retiring of bonds, but it does make the state pay that revenue into the pension plan.

"Placing new hires in a cash balance plan that combines the best features of defined contribution (or 401(k)) plans and defined benefit plan"

This is similar to another aspect of Fortner's plan, as well as the one led by Michael Madigan, although this is only for new employees in the Teachers Retirement System and the State University Retirement System. If it's anything like other states' cash-balance plans, it's basically a hybrid of pensions and 401(k) plans:

For those unfamiliar with cash balance plans, they are sometimes known as "defined-benefit plans in drag." Cash balance plans offer some of the features of both defined-contribution (DC) and defined-benefit (DB) plans. Participants are still guaranteed a minimum benefit and can collect a life annuity upon retirement — which provides more security from investment risks and longevity risks than a private-sector 401(k)-type individual DC account…. Each participant is credited annually with interest (accretion) on the employer and employee contributions, but instead of controlling an individual account and making their own investment decisions, that's all done by the pension board.

[snip]

The cash-balance account of each employee is then credited each year with a minimum return, often set at something close to the government bond yield. So, their money grows at a rate that typically runs a little ahead of inflation and is fully guaranteed by the plan…. Upon retirement, the employee converts the value of the account into an annuity-pension based on the better of the base rate or the phantom values [a dividend] if the markets have been friendly. The actual mechanics are more complicated than that, but those are the key concepts.

Basically the current pension plan promises to pay employees a certain amount come hell or high water. The hybrid plan reduces that amount, then indexes the rest to the depth of the water.

"Allowing cost-of-living pension increases only for the first $25,000 of an employee’s pension" (and $20k for those eligible for Social Security)

This, from what I've seen, is new, and would apply to employees hired before 2011. Madigan's plan would have offered employees a choice: keep the three-percent compounded COLA and give up state-subsidized health care, or keep the health care and drop COLA to 1/2 of the consumer price index. It's basically another means of limiting the effect of COLA.

That employees aren't given a choice may have some bearing on the future of the bill: "In a significant change from previous proposals, the plan does not give participants a choice in retirement options, something Senate President John Cullerton, D-Chicago, said was crucial to helping a pension reform plan survive a court challenge."

Nekritz's defense: "she thinks the plan released Wednesday will survive a legal challenge because it contains a guarantee the state will make its obligated pension payments in the future."

As I understand it, the deal is this: right now state employees don't have a "reasonable expectation" to future pension payments because the system is completely hosed, and the bill would introduce "new advantages" by realistically guaranteeing them pensions in the future.

Take California, which operates under a similar, though less restrictive, pension framework (PDF):

In addition, a number of state courts, such as in California, permit reasonable modifications to an individual’s pension benefits. However, “the modification must bear some material relationship to the purpose of the pension system and its successful operation; and any disadvantage to employees must be accompanied by comparable new advantages” (e.g., an increased pension amount). Thus, as explained by one commentator, the idea is that public employees are not entitled to any particular terms of a pension, but of the substance of the benefit which they could reasonably expect to receive.

So the "new advantage" of the Nektriz/Biss plan (or any others like it) is that the pensions will, you know, actually be paid, which is an advantage over them not being paid. ("Not living in a state which evolves into a fiscally austere hellscape because of decades of pension underfunding" probably wouldn't stand up in court.)

"Increasing employees’ retirement age from one to five years, depending on their current age" and "Increasing employees’ pension contributions"

Employees 46 and up are safe. 40-45, retirement age goes up by a year. 39-35 increases by three years. Below 34, five years. One of the previous problems the state has had is that pension changes cause employees to run for the exits, which is somewhat self-defeating: it adds pensioners and removes people paying into the system. Graduating the retirement-age increases reduces this possibility.

Pension contributions go up one percent in 2014 or whatever the first year after the plan passes is, two percent after that; see above for legality.

The bottom line?

Lawmakers pushing a new pension reform plan said Wednesday they aren’t sure just how much the proposal will save the state if enacted.

Rep. Daniel Biss, D-Evanston, said the proposal must still be reviewed by the state’s pension systems, the sponsors feel “very, very confident, based upon our experience, that this will have extremely significant savings.”

This is one of the many problems Illinois has run into with pension reform. Take, for instance, the Madigan-backed plan, SB 1673 A5. As noted before, it offered employees a choice between keeping their compounded COLA and keeping their health care. This was analyzed by the state's Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability (PDF), but only for one plan, and assuming that half would keep the COLA… which is just a wild guess. So the result was a fairly limited ballpark figure. The legal aspect is a crapshoot; the fiscal aspect will need more vetting than we've gotten in the past.