EDITOR’S NOTE: Whet Moser joins Chicagomag.com starting today as our associate editor. Since 2006, Whet has worked as both a Web editor and associate editor for the Chicago Reader. He has also written for the Chicago Tribune, Slate, and Salon.com.

Whenever I start a new job, I like to express some gratitude to the people who came before me; in this case, it’s three undersung Chicagoans—Ward Christensen, Randy Suess, and Jorn Barger—who envisioned the possibilities of the Web as it came into being.

Ward Christensen It was during a storm like today’s, the Great Blizzard of ’78 (not to be confused with those of 1967 or 1979) that longtime IBM employee and computer hobbyist Ward Christensen started brainstorming a computerized message system, inspired by library bulletin boards, with fellow computer club member Randy Suess. Suess assembled the hardware—a homebrew computer with 40k of memory and a 300-baud modem—and Christensen, who had previously developed the now-legendary XMODEM public-domain file transfer protocol, wrote the code. Only one user could dial into the Computerized Bulletin Board System at a time, and data transferred at about five words per second. Christensen and Suess popularized their systen in the November 1978 issue of Byte (PDF), and despite its extreme limitations, CBBS gained a worldwide following; it was arguably the world’s first open online social network, unless you count Berkeley’s teletype-based, bulletin-board-inspired Community Memory.

In 1985, Christensen gave a surprisingly personal interview over his bulletin board system:

It really IS a "habit" – like a drug, etc. Why else would I be – as I am now – typing at after midnight, having to get up shortly after 6:00 tomorrow, etc. It is just so completely unlimiting, I guess…. I think because I was a loner, I never got interested in the more "humanitarian" things – never got interested in "partying", owning a boat, etc. I HATE driving – being very law abiding, it is unbearable to be placed in a situation of watching everyone else break the law, from failing to signal, to parking in two places, to speeding, – sitting home at my computer is perhaps a sign of "withdrawal".

So that’s why I’m such an irritable driver! Anyway, it fascinates me that Christensen’s obsession with the new medium was so personal—I’m well familiar with the computer screen being an appealing medium for social misfits like me, but Christensen had to build that window to the world himself.

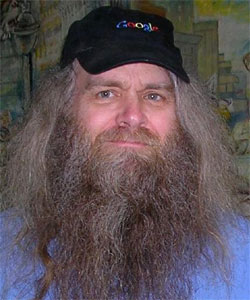

Much later in the development of the Web, another hermetic local would write—or more specifically link—his name into history. Jorn Barger was and remains the spitting image of the Internet oddball—a massively bearded programmer, writer, and James Joyce lay expert who holed up in his Rogers Park apartment for years, culling the nascent Web for links and occasionally taking on freelance projects for subsistence. (This was before reports of disappearances and homelessness which put Web geeks on the lookout for the pioneer—he’s fortunately still with us, particularly on Google Reader and Twitter).

Jorn Barger Barger has been called the world’s first blogger. That’s almost certainly wrong, depending on how you define those things, though he did coin the term "weblog." The first blogger is (probably) Chicago native and Francis W. Parker grad Justin Hall, who in 1997 was noticing that "most of my young friends engage their communities through computer mediation." Hall’s approach to blogging was closer to LiveJournal, an almost-real-time autobiography that’s still going.

What Barger did with Robot Wisdom, the blog he began in 1997, was to take the approach (and software) Dave Weiner developed for Scripting News and expand its intellectual scope; in an influential Feed (RIP) magazine article, Julian Dibbell compared Barger’s creation to

the “cabinet of wonders,” or Wunderkammer, that marked the scientific landscape of Renaissance modernity: a random collection of strange, compelling objects, typically compiled and owned by a learned, well-off gentleman. A set of ostrich feathers, a few rare shells, a South Pacific coral carving, a mummified mermaid — the Wunderkammer mingled fact and legend promiscuously, reflecting European civilization’s dazed and wondering attempts to assimilate the glut of physical data that science and exploration were then unleashing.

Just so, the Web log reflects our own attempts to assimilate the glut of immaterial data loosed upon us by the “discovery” of the networked world. And there are surely lessons for us in the parallel. For just as the cabinet of wonders took centuries to evolve into the more orderly, logically crystalline museum, so it may be a while before the chaos of the Web submits to any very tidy scheme of organization.

Barger’s first post (scroll down on the page) is about a now-defunct page about Chicago gangs (update: now located here). Online journalism nerds of the here and now will note the December 29th, 1997 post, which links to what I assume is the first Web micropayment model: $0.10 a week via a 900 number to follow a debate between web gurus John Dvorak and Jerry Pournelle. The past isn’t dead; it’s just on Robot Wisdom somewhere.

Photos from Wikipedia