Good news! A New York publication says we’re hip! Apparently what’s changed since the last time is that a famous person was elected mayor and Grant Achatz is opening a new restaurant, meaning that we’re now living in "an exciting, excited city in which all these glittery worlds shine" and "whose poise and élan are in flood state." So sayeth Raymond Sokolov, a veteran food and arts writer, who stops short of an explanation: "Nevertheless, there is a mysterious spirit no one can objectively locate that forces the hand of a place or forces things to grow as in a hothouse."

Fortunately, we’ve got numbers that suggest why Chicago’s poise and elan are flooding the hothouse.

This weekend the Chicago News Cooperative published a good piece on the distribution of tax increment finance districts within Chicago. If you’re not up on the concept, here’s how it works: TIF districts freeze the value of the property that can be taxed for general city revenue, and additional property tax revenue–i.e. increments–are driven back into the district to finance development projects. It’s supposed to function as a feedback loop, in which more development generates more revenue, which generates more development.

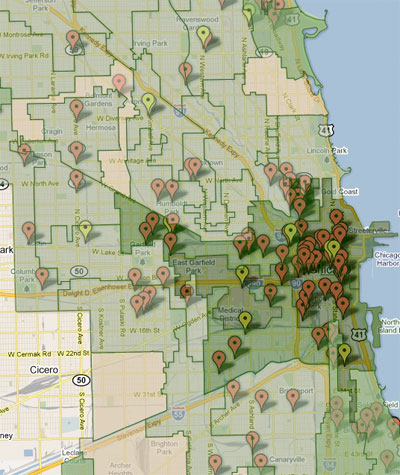

The majority of TIF districts are in or around the Loop, so the vast majority of TIF revenue is spent in and around the Loop. In and of itself this is not breaking news; it’s basically what Ben Joravsky and Mick Dumke found when they looked into the distribution of TIF districts and revenues in late 2009, and what Joravsky has been reporting for years, though the Google Maps implementation is handy.

TIFs, which in part defined the recent mayoral race, entered the city through the Loop; a 1984 Tribune editorial by urban planning consultant Jane Herron called the North Loop TIF (referred to now as the Central Loop TIF) "probably the most detailed plan for public improvements ever put forth by the city of Chicago." In 1986 city comptroller Ronald Picur said it "may be the biggest TIF in the country."

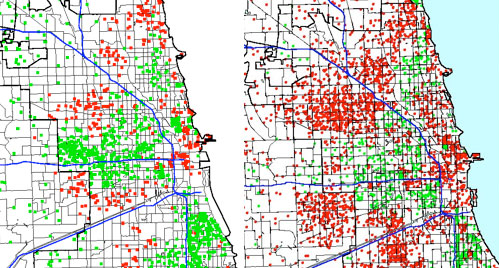

At the time, the Loop was legitimately blighted, and efforts to make the area more attractive for both businesses and residents were ongoing even before the advent of TIFs. And it seems to have worked. Here’s a map of Chicago population change by census tracts from 1980-1990 on the left and 1990-2000 on the right (via the University of Chicago), where red is population growth and green is population loss :

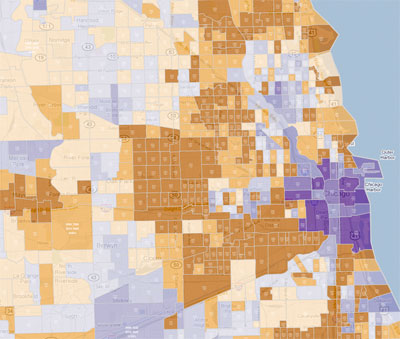

Here’s a similar map from the Tribune, showing population change from 2000-2010:

Now compare that to Chicago Talks’s TIF project map:

The TIF density is strikingly similar to the areas of population growth from 1980-2010.

Chicago has invested a great deal of money in its central business district in the past several decades; as Ben Joravsky points out, $1 billion went into the Central Loop TIF over 24 years (and for all the credit and/or blame given to Mayor Daley, it was Harold Washington who created that TIF in 1984). And it seems clear that the city has gotten a return on its investment, as population and per capita income has increased in the central business district, though not everyone agrees that the return has been overwhelming.

Of course, correlation is not causation. Aaron Renn, aka the Urbanophile, has written at length about the "Europeanization" of Chicago and other major American cities, in which "the core gentrifies and disadvantaged groups and the white working class are pushed further to the fringe." In other words, the same phenomenon is occurring in other cities as well, which leaves the question of whether national and international economic trends are driving public policy decisions meant to capitalize on those trends, or whether public policy is driving those trends. Or maybe it’s not either/or: as in a feedback loop, action and reaction become one and the same.

One of the most famous directives in journalism is follow the money. That’s what Chicago’s done over the past few decades–with, it would seem, some success. If you want to give local pols the benefit of the doubt, you could argue that the focus of time and money on the central business district has secured a foundation for the information and financial industries of the 21st century, and the undeniable attractions inspiring semi-think-pieces like Sokolov’s are the inevitable result of concentrated discretionary income. If you don’t, you could argue that TIF-driven CBD investment has heightened inequality as the rest of the city–particularly the impoverished south and west sides–continues to decline.

The new mayor, whose victory inspired Sokolov’s paean to our glittering hipness, found a receptive audience from industries and wards that have benefited from the city’s fiscal policies. But his easy win was also made possible by the city’s south and west sides. The greatest challenge for Mayor Emanuel will be to stanch the decline of the city outside the central business district, which will likely require fighting prevailing economic conditions rather than riding their waves.