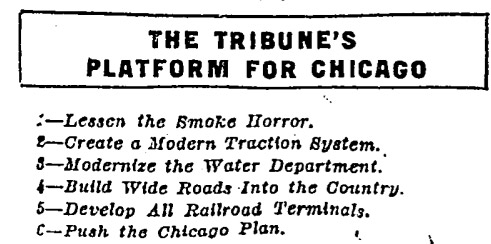

One of my friends was doing some research and sent me the Tribune's 1921 "Platform for Chicago":

City life, same as it ever was: public transportation needs to catch up to the present; the Water Department has troubles; we need to build more roads; the railroads are a mess; we need to have a plan.

And then there's the "smoke horror," what we used to call smog. If, like me, you were born after the Clean Air Act and well after the advent of the environmental movement, it's hard to imagine just how disgusting cities could be. Chicago has been fighting the smoke monster for virtually its entire existence as a city.

1904: "City in Pall of Smoke: State Street is like the Hoosac Tunnel." (A cop stationed in the Loop explained: "There are too many prominent citizens in Chicago.")

1929: "Show Chicago Smoke Kills 6,000 a Year." ("When the wind is from the west 80 percent of the violet rays are cut off from a person on the Municipal pier.")

1956: "Inertia blamed as Chicago Lags in Fight Against Air Pollution." ("Despite a reduction in the average monthly dustfall from 326.41 tons per square mile in 1926 to 52.83 tons in 1955, Chicago has lagged behind other major cities in the control of air pollution.")

Dustfall is a pretty blunt measurement, but here's some perspective: "Dust measurements conducted in large cities in the U.S. in the 1920s and 1930s commonly indicated dust-fall rates in the hundreds of tons per square mile per month. These levels would be considered excessive today, as evidenced by the dust-fall standards of 25 to 30 tons/mi2/month promulgated by many of the states. While the measurement of low or moderate values of dust-fall does not indicate freedom from air pollution problems, measured dust-fall values in excess of of 50 to 100 tons/mi2/month in an area are a sure indication of the existence of excessive air pollution."

In other words, 1920s Chicago had more than three times the "sure indication of the existence of excessive air pollution."

Over the very long term, the city has made considerable progress; the latest advance is the negotiated shut-down of the city's two coal-fired power plants. As in 1956, Chicago has lagged behind its peers:

The statistics in the Chicago metro area add to an already documented problem with asthma among minorities. Chicago has some of the worst asthma rates in the nation, according to various sources, including a 1990 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Chicago hospitalizations for asthma are nearly double the national average, according to calculations by the Respiratory Health Association of Metropolitan Chicago. Nationwide, minorities suffer disproportionately from asthma. The Respiratory Health Association of Metropolitan Chicago reports that the death rate for black people and Latinos are "particularly high" and four to six times higher than it is for white people.

It's been a long fight, and concerns about the city's respiratory health, particularly in low-income neighborhoods, have been at the center of the debate over Fisk and Crawford. But while the closing of the two plants is likely to improve air quality in Pilsen and Little Village, as well as across the city, it may not be a magic bullet for asthma. In 2007, Peyton Eggleston, a doctor at Johns Hopkins and a longtime expert on asthma, looked at "The Environment and Asthma in US Inner Cities," a paper in Chest (the "official publication of the American College of Chest Physicians"). It should come as little surprise that asthma rates and morbidity correlate with poverty, but exposure to outside air pollution is only one criterion. Among Eggleston's findings:

Exposure to indoor allergens has recently been suggested to be a source of respiratory morbidity. Between 70% and 90% of children and young adults with asthma have one or more positive skin test results to aeroallergen, and the frequency is similar in asthmatic patients in urban clinics. The pattern of specific allergen sensitivity differs from that in the general population, with a higher frequency of sensitivity to cockroach and molds and less frequent sensitivity to cats and dogs and house dust mites…. Indoor fungal exposure has been studied infrequently, but a report suggested that contamination is common in urban homes. Therefore, it appears that exposure to fungal and cockroach allergens is characteristic of inner-city homes, leading to more frequent sensitization to these allergens than to house dust mite and animal dander.

A strong association was found in the NCICAS between chronic morbidity from asthma and the combination of sensitization and exposure. The rate of hospitalization in this group was almost three times higher (0.37 hospitalizations per child per year) and unscheduled visits are almost twice as frequent (2.56 visits per child per year) in these children compared to those who were either not sensitized or not exposed, adjusted for gender, family history, and smoking exposure.

The finding of a strong association between cockroach allergen exposure and asthma in the inner city has important public health implications. If it can be shown that disease can be improved by changing environmental exposures, this would support programs to improve housing conditions in the inner city….

We currently have practical measures to reduce exposure to cockroach, rodents, and house dust mite. A report from the Inner-city Asthma Study suggest that these measures, in combination with high-efficiency particulate air filtration and home-based education, are capable of reducing daily symptoms if not emergency department use and hospitalizations.

As Eggleston points out, America has made significant progress in reducing air pollution, but asthma morbidity and mortality rates have actually increased—and the research on indoor pollutants is much less rich.

Here in Chicago, Ruchi S. Gupta of Northwestern has done extensive studies on youth asthma in Chicago; in 2008, he co-authored "The Protective Effect of Community Factors on Childhood Asthma," which looks at a host of societal factors in correlation with asthma in a search for clues:

Some negative community-level physical environment factors, such as neighborhood violence, air pollution, and housing conditions, have also been implicated in affecting childhood asthma prevalence and morbidity.

Neighborhood violence? Yes:

Our findings showed that victimization and having missed school because of feeling unsafe were significantly associated with asthma episodes among students. These findings build on earlier reports on the link between violent victimization and asthma morbidity among inner-city children by documenting that the associations are important across metropolitan areas and that the associations are important in a nationally representative sample of adolescents, not only in high-risk samples.

So what actually helped with asthma rates? Gupta writes:

Overall, positive [community] factors explained 21% of asthma variation. Childhood asthma increased as the Black population increased in a community (p<0.0001). Accordingly, race/ethnicity was controlled. In Black neighborhoods, these factors remained significantly higher in neighborhoods with low asthma prevalence. When considered alongside socio-demographic/individual characteristics, overall community vitality as well as social capital continued to contribute significantly to asthma variation.

[snip]

In a study limited to a comparison of 3268 adults in Chicago, it was suggested that collective efficacy, a measure of residents’ trust, attachment, and capacity for mutually beneficial action, was protective against asthma and breathing problems.

This might sound counter-intuitive, since you can't get asthma from jerks (although it's been suggested that fear and asthma morbidity is related). But in the case of the Fisk and Crawford plants, you can see "collective efficacy" in action: years of organizing and protest that led to today's news.

But as Eggleston suggests, outdoor air pollution is not the only cause of childhood asthma, and may not be the most important pollutant when compared to housing stock. This time, the smoke horror could be coming from inside the house.