It used to be that I couldn't fly home from college—tickets to anywhere within five hours of my home were regularly $500-$700 dollars. I took Greyhound on occasion, but I have atrocious luck on buses. One time a guy was kicked off the bus for threatening to stab a fellow passenger in the heart. One time I was peacefully indisposed in the Union Station restroom when a cop sprung up over my stall and, after seeing that I was minding my own necessary business, proceeded to drag the guy in the neighboring stall out by his legs, mid-cooking-up. One time I couldn't sleep on an overnight bus to Atlanta, not just because of the stops every three hours but because I was constantly wary of the guy with the white-supremacist tattoo. Arriving home bloodshot and shaky was an unpleasant way to begin or end my vacations.

So I took Amtrak, and loved it. I first saw Chicago from an Amtrak train, and it was a romantic vision. Being a college student, I had nothing but time, and the long, long passages by West Virginia's refineries were a chance to catch up on reading. But then I grew up and got a job, and I could no longer afford to move my travel dates around and spend hours longer than even the eternal Styx-crossing of the bus.

So I wasn't surprised to see that 99 percent of the City of New Orleans trains don't run on time, watching Canadian National freight trains pass 'til the day is done. 99 percent: the trains are literally not running on time, within the margin of error.

More than 4,000 instances of freight train interference on Amtrak's City of New Orleans route and on Amtrak service between Chicago and Carbondale were counted on the CN-owned rail lines last year, Amtrak said in the complaint. The delays totaled the equivalent of more than 26 days, Amtrak said.

[snip]

Amtrak's complaint marks the first test of a provision in a 2008 law that established on-time performance standards as part of a program designed to improve passenger rail travel. The goal is for trains to arrive at their final destinations within 15 minutes of the schedule at least 80 percent of the time. The law is being challenged in court by the Association of American Railroads, which represents the freight rail industry.

[snip]

Amtrak asked the Surface Transportation Board to investigate the causes of the delays on CN tracks and to determine whether CN is systematically violating a federal law that grants preference to passenger trains over freight trains. The board can fine CN to deter future violations.

But it's not like Canadian National has an easy time of it in Chicago. The city is the most important hub of rail traffic in the country—the only city serving six of the seven major rail companies and accounting for a quarter of the nation's freight rail traffic—and it's also the worst rail bottleneck in America. This got a brief burst of attention during the mayoral election, when longshot candidate Patricia Van Pelt-Watkins put it on her platform, but it's a vast and ongoing problem. It's an issue for drivers, because of the 1,900 grade crossings, the most in the country; a two-mile-long "monster train" can shut down all of Barrington's grade crossings. It's an issue for train commuters, because of the 7,500 hours of delays. It's an issue for big business, because it can take two-thirds as long to get across Chicago by rail as it takes to get from Chicago to Los Angeles. According to IDOT, 20 percent of a freight train's commute is delay.

As bad as it is for commuters, it's no better for the freight companies. That's the crux of the issue with Amtrak's complaint: passenger trains are supposed to get preference. But there's simply not enough capacity, and what exists is limited by outdated technology. And it's just going to get worse; freight rail traffic is projected to increase 89 percent in the next 23 years. Rising fuel costs are driving the expansion of rail traffic, and while Chicago will likely continue to retain its lead, other cities are building out their rail capacity to adjust to supply-chain changes:

To keep costs down, shippers are increasingly keeping products aboard slower but more cost-efficient rail and sea transport for as long as possible, while working to minimize air and truck freight, the report says. Shippers that once used rail only for longer trips are now making shorter hauls between a series of interlocking transit hubs.

It's a mess, and it speaks to the neglect of the nation's rail system, an awkward combination of public and private interests in which there are no good guys:

For decades, railroads were also slowly crippled by state and federal laws that forced them to run money-losing passenger trains and to keep on featherbedding employees rendered obsolete by new technology. Rail companies, as private-sector entities, remained responsible for maintaining their own infrastructure and for paying increasingly high property taxes on it, even as public money poured into highway and airport construction.

[snip]

By the start of the ’80s, the government had eased some of the policy constraints on the railroads, giving them relief from running passenger trains without compensation and a substantial measure of price deregulation. But by then the damage was done. Thinking their industry was in terminal decline, many railroad managements continued to tear up tracks and use what little capital they had to diversify into new businesses, like theme parks, and, in one instance, even mutual funds.

[snip]

But then, starting in the late ’80s, something unexpected happened. As fuel and labor costs rose, and highway congestion worsened, more and more shippers started looking for an alternative to trucking. Once reduced to transporting mostly heavy, low-value commodities such as coal, railroads started gaining business in the transport of more time-sensitive, high-value items—everything from Japanese computers to California wine—typically using containers double stacked on flat cars. On routes where they still have adequate infrastructure, railroads have won back fantastic amounts of business from trucks, especially on long hauls such as Los Angeles to New York, where railroads now have a 72 percent market share in container traffic and could have more. Railroads have gone from having too much track to having not enough. Today, the nation’s rail network is just 94,942 miles, less than half of what it was in 1970, yet it is hauling 137 percent more freight, making for extreme congestion and longer shipping times.

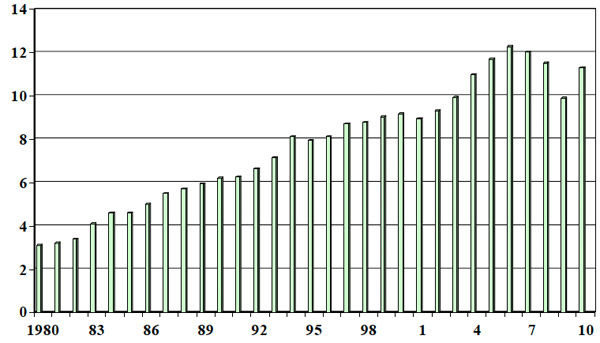

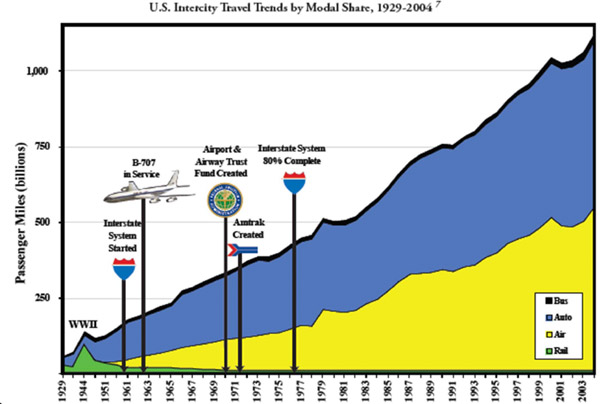

Two USDOT charts show the increase of freight traffic as compared to the disappearance of rail travel (the first represents loadings in millions of units; PDF):

But in Chicago there's not adequate infrastructure. The public-private, city-state-and-national CREATE program emerged out of the 1999 blizzard, which practically shut down the city's rail system, delaying the time-sensitive, high-value items that were increasingly put on the rails. Some of the signals replaced by CREATE almost made it to their hundredth birthday.

The railroads made Chicago, turning its modest waterway advantages into a hub that linked the east with the west. The transport of goods through the city created its futures industry, which has survived in virtual form. As William Cronon wrote in Nature's Metropolis:

Whether breaking up bulk shipments from the West, it served as the entrepot—the place in between—connecting eastern markets with vast western resources. In this role, it became a key participant in a series of economic revolutions that left few aspects of nineteenth-century life untouched. Henceforth, Chicago would be a metropolis—not the central city of the continent, as the boosters had hoped, but the gateway city to the Great West, with a vast reach and dominance that flowed from its control over that region's trade with the rest of the world.

Trains no longer inspire romance; cars have taken their place in our hearts. But that's a tough romance these days, and the country's now in a race to repair its relationship with the rails, as Chicago clings to its place as the nation's heart, keeping the blood flowing.

Photograph: Library of Congress/Jack Delano