The Trib just conducted a poll of Illinois voters throughout the state on national fiscal issues. The conclusion? #VALUE!:

* Statewide, 48 percent think a federal tax increase is not necessary to "reduce the national debt problem"; 42 percent think it is.

* 49 percent think cutting government services should be the "main focus of lawmakers" to balance the federal budget; 29 percent think the main focus should be an increase in taxes ("both equally, neither, or unsure" isn't shown).

* 59 percent think the federal tax code favors "high income people."

* 67 percent agree that taxpayers earning $1 million or more should pay an income tax rate of 30 percent, including 59 percent of downstate voters, the most reliably conservative region of Illinois.

So the simple conclusion that any sensible politician will come to is that the rich don't pay enough in taxes, and that that needs to be corrected, but it shouldn't be the main focus in balancing the budget and isn't necessary to decrease the national debt. I think we're looking at a big opportunity for… well, not so much a centrist party as a schizophrenic one.

The gist seems to be that Illinois residents think we should change the tax code out of fairness, not practical reasons. Which is inevitably a confusing rabbit hole, because you can look at it this way:

"The burden doesn't need to be on those who are already paying," said Susan Rippinger, 54, who works with her husband. "If the nearly 50 percent who are not paying any taxes were contributing, we would have a better scenario. It's not fair to go after those who are working hard and not those who are doing nothing."

"Part of living in a country such as ours is paying taxes. I don't see why some people see it as negative. The tax brackets were higher under previous administrations," he said, referring to the time before the tax code was changed under President George W. Bush. "What's wrong with taking it back to where it was?"

The problem is that no one wants to do that:

Taxes are lower under both [Obama and Romney] plans than they would be if we simply let the Bush tax cuts expire and returned to Clinton-era rates. Then, taxes would be closer to 20.4 percent of GDP. You wouldn’t know that from the admiration with which Democrats talk about Clinton’s economic policies, or the horror with which Republicans talk about Obama’s tax ideas.

This all reminded me of the New York Times's excellent recent piece on Chisago County, Minnesota, on the Minnesota-Wisconsin border, and its residents' attitudes towards government spending and government aid. The reporters, Binyan Appelbaum and Robert Gebeloff, got similarly mixed-up responses from Chisagoans:

The government helps Matt Falk and his wife care for their disabled 14-year-old daughter. It pays for extra assistance at school and for trained attendants to stay with her at home while they work. It pays much of the cost of her regular visits to the hospital.

Mr. Falk, 42, would like the government to do less.

“She doesn’t need some of the stuff that we’re doing for her,” said Mr. Falk, who owns a heating and air-conditioning business in North Branch. “I don’t think it’s a bad thing if society can afford it, but given the situation that our society is facing, we just have to say that we can’t offer as much resources at school or that we need to pay a higher premium” for her medical care.

I like Ta-Nehisi Coates's explanation for this:

[W]hat I strongly suspect is the sort of shame you see in Mr. Falk's is neither crazy, nor ignorant, nor shocking, once you think about it. We all want to be cowboys. More, we sometimes want leaders who push toward that imagined self, as opposed to our statistical self.

It would certainly explain the conservatism of regions where the percentage of income that derives from government benefits—which is up nationwide, going against upper-income taxation trends—tends to be higher. (Downstate, most counties are up above 20 percent.)

One thing to note about that wonderful map is that the only two government programs that increased consistently from 1969 to 2009 as a percentage of income were Medicare and Medicaid. For instance, Social Security increased from 3.4 percent in 1969 to 5.6 percent over that period, and there was one decade-over-decade drop. Medicare, on the other hand, increased every decade: from 0.9 percent in 1969 to 4.1 percent in 2009, the largest gainer of the various government benefits. Obviously, it's a combination of increasing health-care costs and the aging of the population. And it's probably the hardest thing to reduce spending on, because it cuts across classes… and because it involves mortality:

Without Medicare, Mr. Kopka said, the couple could not have paid for the treatments.

“Hell, no,” he said. “No. Never. She would have to go blind.”

And him?

“I’d die.”

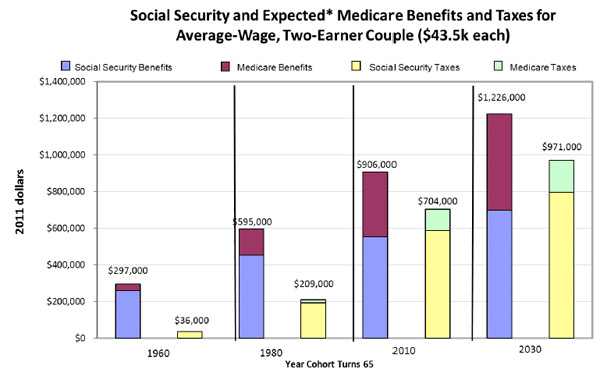

A two-earner couple each earning a wage of $43,000 that turned 65 in 2010 will have paid $116,000 in lifetime Medicare taxes. And they can expect to get $351,000 in benefits. A high-wage statistical-construct couple, with a combined income of $113,100, will get the same benefits, having paid in $149,000.

Well, it's a problem insofar as everyone wants to cut back on government benefits, as noted above. But the fastest-growing benefit is the one that keeps people from dropping dead, so it's really popular. And no one wants to raise taxes to pay for it. They want to raise taxes out of fairness, maybe, but not to pay for benefits. Unless they think that raising taxes is unfair. So you end up with a lot of dissonance:

She believes that she is taking more from the government than she paid in taxes. She worries about the consequences for her grandchildren. She said she would like politicians to propose solutions.

[snip]

But she cannot imagine asking people to pay higher taxes. And as she considered making do with less, she started to cry.

She's probably right that she's taking more from the government than she paid in taxes, at least in terms of benefits (depending on her health). But she doesn't want to raise taxes on anyone. And wants politicians to figure it out. And she's not alone in this. And what we're telling them to do, basically, is this:

They’re looking at a small corner of the budget, the 12.3 percent known as non-defense discretionary spending. The stuff that’s not Medicare, not Medicaid, not Social Security or the military. It’s the odds-and-ends, so to speak.

[snip]

The budget ends up like the yard of a man who owns only a lawnmower: The grass is trim, but the trees are overgrown and the ivy is everywhere and the gazebo is falling apart. Yet we keep mowing, because that’s what we feel able to do.

This is where I start to feel sorry for the corrupt/feckless/incompetent/etc. politicians who we complain so bitterly about. Tending to both the imagined and real selves of their constituencies, at the same time, is bound to make a person two-faced.