I don't think it's exaggerating much to say I came to Chicago for the music. One of my first memories of the city was buying Uncle Tupelo's Anodyne at Dr. Wax in Evanston when I was 16; that led to discovering Freakwater and the Waco Brothers, and the realization that the city had really picked up the torch of country in a way that the South itself hadn't done. Despite my relative ignorance of indie music, I wrangled a part-time slot writing reviews for my college paper, which got me into shows I couldn't afford to buy tickets for. I recall one night early on catching the New Pornographers at the Abbey Pub, which, from Hyde Park, seemed like it practically bordered on Wisconsin.

They closed the set around two in the morning; I got lost and ended up at 45th and Indiana around three—what? this was, like, before smartphones—and made it back to my friend's apartment around four, five hours until my flight was due to leave.

It felt great.

Now I don't go to shows much anymore. Maybe it's because I'm old and don't like to be out late, by which I mean after eight. But in my habits, and those of the people around me, it seems that foods have supplanted the arts. It used to be I'd shovel whatever cheap foodstuff was closest to the venue. Now, the restaurant is the destination. I have friends and family in bands and the theater, but when it's time for a night out, we go for dinner dates.

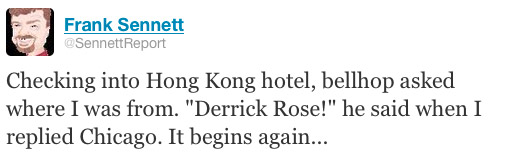

This is all anecdotal, of course. But I was reminded of this when I was paging through Chicago's just-released 100 Most Powerful Chicagoans. Money and politics are power, so obviously most of the figures are CEOs or politicians. Of the top ten, eight are public servants or powerful businesspeople. The exceptions are Derrick Rose, a bit of a surprise at #7, though maybe I shouldn't be that surprised…

… and Grant Achatz at #9, coming in just behind Penny Pritzker and just ahead of Groupon's Eric Lefkofsky.

So I started paging through and counting up their industries. Seven restaurateurs (which I thought was restauranteurs before I started working in Chicago media, since I had no prior use for that term) made the list, from Rick Bayless at #35 to Tony Hu at #96. By comparison, all the arts combined made up eight entries on the list—five of which are theater and comedy, the exceptions being Douglas Druick of the Art Institute, Deborah Rutter of the CSO, and Vince Vaughn—unless you count Roger Ebert, Jeanne Gang, or Ikram Goldman. Bayless needs another play or two under his belt before he gets cross-listed.

Granted, this is still anecdata. I don't know exactly how you'd test who in Chicago wields the most power, outside of a 100-person mayoral runoff (my guess: Rose, Rahm, Patrick Fitzgerald, and Theo Epstein in the final four). But it's fairly useful anecdata, insofar as it represents the considered opinions of a bunch of people who think about Chicago as their jobs. And it's an interesting metric: power.

I have a theory about this. The prevalence of electronic media has shaken the foundations of the arts, democratized them and put them up for grabs. Ten years ago, when I came to Chicago, the people who did bookings at the venues around town played a vital role in shaping my listening habits; now, with virtually all the music being created at my fingertips, I can barely follow who's who, much less decide what concert I want to go to.

Food, on the other hand, is inevitably live. Until Grant Achatz figures how to replicate Alinea in pill form, the only way to appreciate his work is to go to the restaurant. You can't download it, or get it on Amazon. Chicago's long been the crossroads of the country's ingredients; now we've figured out how to cook them.