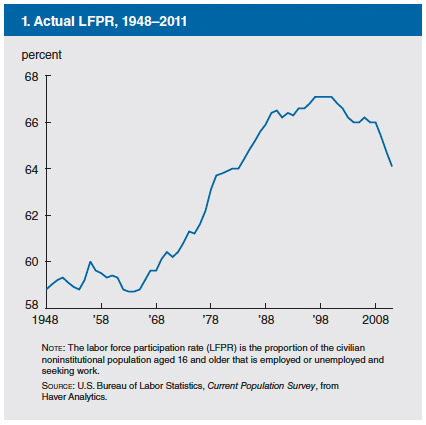

The Chicago Fed just released a paper, "Explaining the Decline in the U.S. Labor Force Participation Rate," which seeks to explain why the LFPR has declined so sharply after peaking at 67.3 percent in 2000 (PDF):

The reasons for the increase are mostly what you'd expect, boomers and more women in the workforce. But there's this, too:

Third, improvements in health technology may have boosted labor force participation directly, by improving the health and longevity of the work force, and indirectly, by requiring individuals to work longer (retire later) to accumulate enough wealth to support lengthier retirements. Finally, rising rates of return to skills, particularly during the 1980s and 1990s, encouraged human capital investment, resulting in a shift away from manual labor occupations, which tend to have shorter average career lengths.

Then there's the massive decline. Obviously the terrible economy has something to do with it. "Labor force participation" (which peaks at around age 50) means "people who have jobs or are actively trying to get them," and high unemployment and long, frustrating job searches are bound to have led some people voluntarily out of the labor market. But how many are "discouraged" as opposed to just retired, since it's not far from peak labor-participation age to retirement age? There's an art to predicting it:

We include indicators for every single age to account for the typical lifetime pattern of labor force participation—e.g., individuals work less frequently while in school and later in life. Year-of-birth indicators reflect unobservable work behavior, ethics, and norms that are specific to birth cohorts (“cohort effects”); e.g., the model allows that, at the same age, a cohort born in, say, 1954 might be more or less likely to work than another born in 1978. We estimate this model separately for 44 combinations of age (16–19, 20–24, 25–54, 55–70, and 71–79), gender, and educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduates, some college, college graduates, and some postcollege education).5 This allows the cohort effects and other controls to flexibly vary across age, gender, and education.

This is pretty important stuff, because that's how we decide what to tell ourselves about unemployment, which is more a ratio of who has jobs to who we think really wants a job. And that's political:

Some Republicans and conservatives are seizing upon this figure as evidence that the economy is still in the tank. It is certainly true that the participation rate is considerably lower than it was when Obama came to office, reflecting the fact that some people have dropped out of the labor force and fewer new workers have joined it. In January, 2009, the participation rate was 65.7 per cent. If it were still at that level, the unemployment rate would be two points higher.

[snip]

The over-all picture, then, is of a labor market that is picking up but still operating at a much lower level of intensity than it did ten or fifteen years ago. Much of the shortfall is a lingering effect of the recession. But given that the participation rate and the employment-to-population ratio have been falling for more a decade, at least part of the change may well represent a permanent development caused by the aging of the baby boomers.

That's John Cassidy on the Case of the Missing 1.2 Million, which has been burning up the blogosphere and the financial networks.

And that's what the Chicago Fed economists conclude: "standard labor market measures used to compute gaps in resource utilization, such as the employment-to-population ratio and the LFPR, should reflect these long-running patterns." But it's not just baby boomers—the Fed authors also point to the decline in teenager participation in the labor force as an ongoing change. Questions like that are particularly difficult: are they being crowded out of the market as high unemployment gives employers more choice of workers, or are they simply staying in school? Behind the basic unemployment numbers you hear every day are those sorts of dilemmas, calculating behind the scenes how we talk about employment around the water cooler.