One of the most interesting things in the City of Chicago's recent analysis of pedestrian traffic accidents, which I dealt with briefly in my post on speed cameras, is the correlation between crime and serious pedestrian accidents:

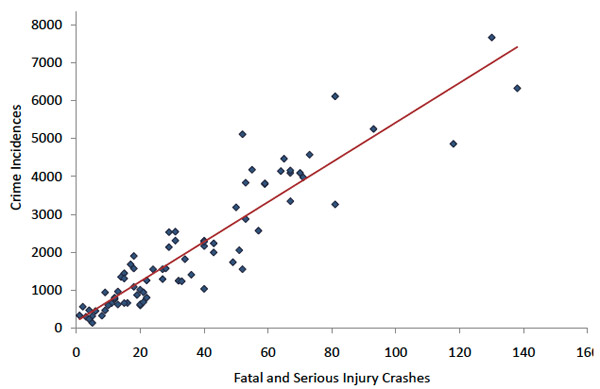

Numerous social and demographic characteristics, including crime, income, race, language spoken and walkability index, were analyzed to identify correlations with pedestrian crashes. The strongest correlation was found between crime and fatal and serious injury pedestrian crashes.

Here's what it looks like:

This is not a new phenomenon:

There are some good examples of work linking existing theory to the issue of road safety, in considering whether deviant road user behavior is just one aspect of a more general deviant tendency. Junger and Tremblay (1999), publishing in the criminological literature, have produced evidence that crime has a non-spurious positive association with road traffic accident involvement. Robert West and Marianne Junger collaborated (1999) to show that school children aged 7-15 who were in the top 25% of the distribution for problem behavior where three times more likely to be involved in a road traffic accident than were those in the lowest 25%.

More from Tom Vanderbilt, author of the great book Traffic:

[T]here is the idea, related to the link between on-and-off-road criminality, that targeting traffic violators might be an effective way to combat other crimes. Which brings us to the third benefit of traffic tickets: increased public safety. Hence the new Department of Justice initiative called DDACTS, or Data Driven Approaches to Crime and Traffic Safety, which has found that there is often a geographic link between traffic crashes and crime. By putting "high-visibility enforcement" in hot spots of both crime and traffic crashes, cities like Baltimore have seen reductions in both.

Marianne Junger, Robert West, and Reinier Timman on "Crime and Risky Behavior in Traffic: An Example of Cross-Situational Consistency" (PDF, 2001):

Log-linear analyses, controlling for gender and age, revealed that persons who displayed risky traffic behavior leading to the accident had an odds ratio of 2.6 for having a police record for violent crime; of 2.5 for vandalism, 1.5 for property crime, and 5.3 for having been involved in traffic crime. The results were consistent with the idea of a common factor underlying risky behavior in traffic and criminal behavior.

The idea being that in an area with more criminal behavior will have more generally irresponsible behavior, and thus more traffic accidents. It presents a significant problem in locating the cart and the horse—Vanderbilt ties it into the "broken windows" theory—but it's interesting.

The Tribune talked to the great-grandmother of Diamond Robinson, whose death has become part of the speed camera narrative. Here's part of what she had to say:

Jeanette Tucker, the girl's great-grandmother, said she backs the idea of speed cameras but realizes they would have done no good for Diamond.

"The speed cameras wouldn't have helped save Diamond's life," she said. "What you need is stop signs and lights."

She's got a point. Steven Vance makes the point that New York City's considerable recent success in reducing traffic fatalities follows traffic calming projects and other safety upgrades. He also has a nice photographic comparison of one risky intersection in Chicago—at Milwaukee and Augusta, just north of an interstate on-ramp, one I've biked and that makes me nervous for exactly the reasons Vance indicates—with better designs from bike-friendly Copenhagen. Separate bike signals clarify the actions of drivers and bikers at intersections where there are a lot of options.

We should at least give ourselves some credit for progress made over the past 80 years. In 1935, Chicago's traffic fatality rate per 100,000 was 22.3. 780 people were killed in traffic accidents that year. In 2008, it was 5.89. (New York, for what it's worth, also had a considerably lower traffic fatality rate than Chicago in 1935, at 14.2 per 100,000.) In 1934, over a thousand people were killed in automobile fatalities in Chicago. It's really hard to exaggerate how deadly our city streets were in the early 20th century.