I read the Tribune's editorial on the occasion of Jesse Jackson Jr. pleading guilty, which focuses on gerrymandering, and something about it seemed not quite right:

I read the Tribune's editorial on the occasion of Jesse Jackson Jr. pleading guilty, which focuses on gerrymandering, and something about it seemed not quite right:

Jackson throughout his career has been one among hundreds of congressional candidates of both major parties, running for seats in both houses, who raise bushels of campaign money that they don't need.

So far so good. But:

No, gerrymandering didn't drive the ex-congressman to a life of crime. Gerrymandering did, though, enable it. With no viable opposition, he had little need to buy expensive TV time — and, to be frank, he had fewer pesky journalists going line by line through his campaign finance reports. More scrutiny might have detected questionable spending patterns.

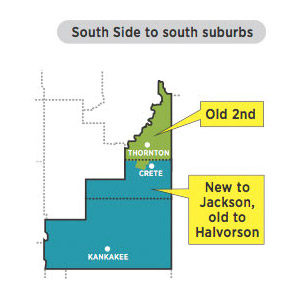

It's not that the 2nd district hasn't been gerrymandered, it's just that it wasn't necessarily gerrymandered to protect Jesse Jr. The opposite is (mildly) true: Jr.'s district, which was once a smaller, more Chicago-focused, more dominant Democratic district, was recently gerrymandered during his tenure in ways that made him more vulnerable for the benefit of other Democrats.

I cast my reaction out on Twitter and got some thoughtful responses: "what that article completely misses is that it insulates him from a legitimate general election challenge, not primary"; "He took out Beavers, Shaw Brothers, he bucked Madigan. He had plenty of people eyeing him and his org."

In regards to the first one, Chicago actually singled out Jackson's district as a newly competitive primary because of the recent redistricting:

The eight-term incumbent, Jesse Jackson Jr., faces former U.S. Rep. Debbie Halvorson (11th) in the Democratic primary. Jackson has the edge, but Halvorson has previously represented a third of the redrawn district, all of which is new to Jackson. Either Jackson or Halvorson will likely win in November; in 2010, more than seven out of ten voters here picked Democrat Pat Quinn over Republican Bill Brady.

Why would Team Madigan put Jackson on the hot seat with a massive expansion of the district, out past Kankakee? Political conflict is one argument, but another is a divide-and-conquer strategy. If you want a maximum number of Democrats, you want more safe-but-not-too-safe districts, as Edward McClelland wrote last year:

Democrats usually underperform their popular vote margin due to patterns of racial segregation that concentrate African-Americans in inner-city districts, where their candidates win 80 or 90 percent of the vote. Madigan solved this problem by extending urban districts into the countryside — Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr.’s 2nd District stretches all the way to Bourbonnais, home of his Republican opponent, Brian Woodworth. Gerrymandering, it turns out, may be necessary for democracy.

The 2nd district has been growing since well before Jackson arrived. Before Dems blew it out to encompass places like Bourbonnais, it was extended out to Homewood and Flossmoor—by the state GOP, who wanted to knock off Gus Savage in favor of the more moderate Mel Reynolds, who got crossover votes after the redistricting. The 2nd is also one of the districts that was shaped by the Voting Rights Act, which guaranteed the city three majority-minority congressional districts. It's been insulated, but insulated by federal law, not just by the mind of Madigan.

(Update: speaking of the Voting Rights Act….)

As to the second point, the editorial doesn't give Jesse Jr. his due. As Steve Rhodes wrote in his excellent profile of Jackson for Chicago, he was a good politician: he built a machine, brought home the bacon to the district, and was a good retail politician. And that's basically how you get re-elected. Jackson's district was insulated from Republicans, but not from other Democrats.

While he was seeding his district with federally funded projects, Jackson was also building his own political minimachine that disposed of hack after hack in the predominantly African American wards in the city and the south suburban legislative districts. He replaced the departees with supposedly reform-minded politicians who fit his mold….

Jackson’s political organization, says Don Rose, the veteran political consultant, “isn’t like the old machines of yore, built on a huge army of workers rewarded with patronage jobs, but is more candidate based, in which Jackson trades his technical know-how and campaign apparatus and strategies.”

It was brilliant in its own way. Jackson endorsed reformers over previously immovable party regulars, regardless of race or party. It burnished a brand and also built a coalition that he hoped would prove useful down the line.

And the things Jackson wasn't as good at made him vulnerable within the party: "Not hewing lockstep to the party line kept him from rising into Democratic leadership, as did his distaste for party fundraising (which helped Rahm Emanuel gain influence)."

All of which is a long way of saying: gerrymandering is extremely complex, and Jesse Jr.'s district is a Democratic garrison for reasons beyond mere state-Democrat gerrymandering.

But! That doesn't mean gerrymandering isn't a problem. And there are sensible fixes just laying around for someone to pick up.

Republican state rep Mike Fortner, whose other job is physics, has been a go-to source for his colleages on the mindbending data of redistricting. But he's also looked beyond the current politics of remapping towards an alternate, award-winning model, one meant to maximize competition across the state. A couple years ago, Fortner took on the challenge to redistrict Ohio in a computer-judged contest, and won—though all the publicly-submitted maps were more sensible and fair than the politically-generated ones:

Illinois Rep. Mike Fortner, a West Chicago Republican, did that in Ohio’s public contest. He submitted one of the top three plans for that state’s congressional map. Although it was a test run based on 2000 data, Fortner says, “One thing that they found was that every one of the publicly submitted plans beat the score of the map that was actually approved by the Ohio legislature.”

The Ohio secretary of state sponsored the contest and provided access to geographic information systems, or GIS, mapping software on the Ohio State University’s Internet server. Each user applied in advance and got a secure account. They had to follow certain criteria, such as drawing compact districts.

Fortner’s map for Ohio produced rectangular districts and would have resulted in nine Republicans, eight Democrats and one virtual tie.

His model generated sensible-looking (if you think that doesn't matter, ask a political nerd about the 4th congressional district sometime), geographically logical districts that increased the number of competitive seats. Back in 2009, Fortner proposed enshrining the concept in the Illinois constitution. Complex as redistricting is, Fortner's amendment was conceptually pretty simple: districts should be "compact, be contiguous, be substantially equal in population, reflect minority voting strengths, promote competition, and consider political boundaries." Those criteria are scored; the maps with the top three scores go to a vote requiring a 3/5ths majority to pass, so the parties basically have to agree; if they can't, the Secretary of State automatically certifies the map with the highest score.

It's pretty reasonable, and it lays out an explicit, in some ways quite simple public framework for the arcane process. It does require pols to surrender power to an abstract framework, which is a leap—not just for Democrats and their supermajority, but for Republicans, who (someday!) might retake the legislature and seek to build on those gains. But if people believe that partisan gerrymandering creates moderate, reliable power that corrupts moderately and reliably, Fortner's idea is a concrete alternative.