Via Coudal, the Art Institute has a wonderful online exhibition to coincide with its "Picasso in Chicago" exhibit (here are five things to see): a virtual tour of the Armory Show when it hit Chicago in 1913. I love how it starts with a view of the Art Institute from when Chicago was still a very young city.

How did the young city react? As you'd hope, given the historical context of the Armory Show (which at the time had the pleasantly bureaucratic title of the "Association of American Painters and Sculptors" show, as if it was a union get-together).

After the clickbait headline, Harriet Monroe's preview from New York was friendlier: "It is enthusiastic, exuberant; it offers the glad hand to any one, young or old, who has something special and personal to say in modern art. And its welcome is generous; each man has space enough for all his moods…. We cannot always tell what they mean, but at least [the cubists] are having a good time."

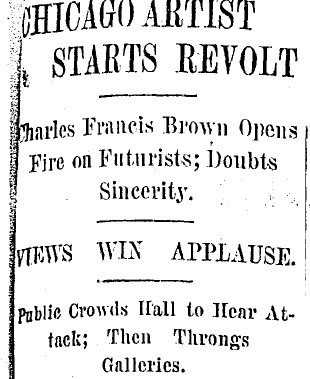

The official voice of artistic conservatism in Chicago at the time was Charles Francis Browne, a well-regarded landscape painter (you have to be something of a conservative to be an Illinois landscape painter, even if Browne slowly came to the realization that Impressionism was one way to make the state's extremely modest beauty interesting). Browne was amusingly unimpressed by the Armory Show.

And a nice dig in that last subhed too; really just well played by everyone.

"IT'S trying to prove ITSELF by ITS own ITNESS," Browne told his audience; if shortsighted, at least it's well phrased. The reaction in Chicago was more skeptical than the show's first stop in New York City… but we outdrew the Big Apple, too.

While the New York press was generally favorable, often full of praise save for some cranky responses from the city’s establishment critics, the show’s reception at its next stop, The Art Institute of Chicago, was far less gleeful. The Institute’s academic student body staged public protests during the exhibition and even burned in effigy the figure of Walter Pach. Today this display sounds gruesome, but I suspect at the time it was meant to be somewhat jocular. Pach, after all, never went into hiding during his stay in the Land of Lincoln. In fact, this free publicity helped boost the Chicago run of the show, a smaller version of New York stripped of its American art component. At 100,000, Chicago had the highest attendance numbers of all three venues, compared to 87,000 in New York.

Through the mists of history, it's hard to tell what's trolling.