Madison Street following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

It's not often that I end up pondering Newt Gingrich's ideas with some interest:

The former Republican primary candidate has been on about this for awhile. I can see where his ideological opponents view it as a trap, but that's a narrow view of the possibility and potential of such hearings.

In 1967, a year that major riots hit 75 U.S. cities, Lyndon Johnson appointed the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, better known as the Kerner Commission after its chair, then-Illinois governor Otto Kerner. It had a small, august board: two senators (one of whom was the first popularly elected African-American senator, Edward Brooke of Massachusetts), two representatives, the mayor of New York, military contractor and former Air Force wonk Tex Thornton, the head of the NAACP, the president of the U.S. Steelworkers, Atlanta's top cop, and the commissioner of commerce for the state of Kentucky.

None were radicals of any kind. But they produced a document in 1968 that shocked the country and became a bestselling book (it's still not hard to find in used book stores). Here's why it shocked people: "This is our basic conclusion: Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal." And it only got more scathing from there.

What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain, and white society condones it.

[snip]

White racism is essentially responsible for the explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities since the end of World War II.

[snip]

A climate that tends toward approval and encouragement of violence as a form of protest has been created by white terrorism directed against nonviolent protest; by the open defiance of law and federal authority by state and local officials resisting desegregation; and by some protest groups engaging in civil disobedience who turn their backs on nonviolence, go beyond the constitutionally protected rights of petition and free assembly, and resort to violence to attempt to compel alteration of laws and policies with which they disagree.

Kenneth B. Clark, the first African-American president of the American Psychological Association (and famous, with Mamie Phipps Clark, for their doll experiments) noted that the issues surrounding the Kerner Commission report were essentially the same as those of the famous 1919 report on Chicago's race riot and others like it, telling the Commission:

I read that report. . . of the 1919 riot in Chicago, and it is as if I were reading the report of the investigating committee on the Harlem riot of '35, the report of the investigating committee on the Harlem riot of '43, the report of the McCone Commission on the Watts riot.

I must again in candor say to you members of this Commission—it is a kind of Alice in Wonderland—with the same moving picture re-shown over and over again, the same analysis, the same recommendations, and the same inaction.

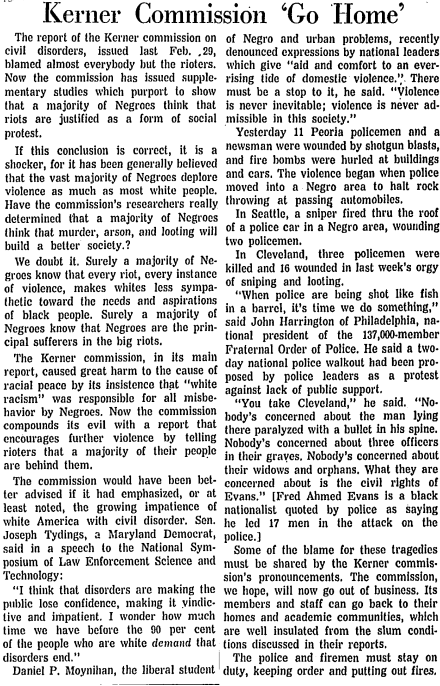

It was not well received. The Tribune editorial page—which had been hostile to Martin Luther King two years prior, suggesting that he be charged with inciting violence under racketeering laws—lashed out at the governor's report:

(This is somewhat misleading; a section of the report outlined means of providing local law enforcement and public safety officials with federal coordination on the level of the National Guard and Army.)

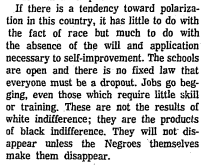

The paper followed up with an editorial—one of several blasting the Commission—entitled "Myth of Two Nations":

From the Johnson administration, the report was met with ambivalence. By 1968 Johnson had implemented most of his Great Society programs, was consumed by the Vietnam war and losing his once-great political power, and a month later declined to run for re-election; as a specific list of political goals, the Kerner Commission report immediately withered.

But it also left a significant legacy. It pushed the media to diversify its hiring practices and reconsider the way it reported on crime and social issues. It changed the way economists approached economic development and housing policy. It shaped the way our cities are policed (PDF). And it shaped our cities physically, as HUD director George Romney adapted the report's recommendations on housing:

In the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and another round of nationwide rioting in 1968, Congress finally passed a fair-housing law, but its practical impact was yet to be determined. Secretary Romney could interpret the law narrowly, simply as a prohibition against further discrimination, or see it as requiring HUD, based on vague language in the statute, to take steps “affirmatively to promote” racial integration across the metropolitan landscape. He chose the stronger interpretation and determined to implement a Kerner Commission recommendation that six million new low- and moderate-income public or subsidized housing units be placed largely in white suburbs.

The Kerner Commission was set up to address crime trends in the inner city; what it produced was an ambitious, wide-ranging analysis of urban life in the late 1960s, grounding it in the history of American cities up until that point and bringing to bear a wide range of disciplines on the subject. Its direct, immediate effect on politics and urban planning was muted, due in large part to its timing at the weak end of the Johnson administration. But its more subtle, long-term effects were important in framing how politicians and planners view the issue today (it was also very, very big news at the time). "Every federal administration since 1968 has wrestled, to some degree, with the predictions of the Kerner Commission and their policy options," wrote the University of Michigan's Reynolds Farley on the 40th anniversary of the Commission (PDF). It's a long reach for one government comission, and perhaps due to be refreshed.

Related: "The Night Chicago Burned," on the legacy of the April 1968 riot in Chicago, by Gary Rivlin.

Photograph: Chicago Tribune