Because of Chicago's murder rate—better this month, but depressingly high in January and much of last year—the national media has periodically been checking in on the city and its myriad social problems. Sometimes it's been shoddy, sometimes the reporting has a bit more texture. What's been frustratingly uncommon has been a sense of historical, social, political, and economic context, a particular shame since Chicago, the birthplace of American sociology, is arguably the most studied city in the country. There's a wealth of literature going back through its years as an urban laboratory, critical to its current nature.

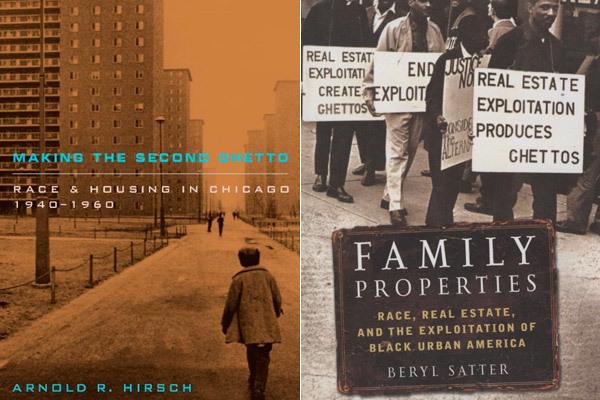

So I've been heartened to see one writer hosting a virtual book salon on two of my favorite mostly overlooked books on Chicago, Ta-Nehisi Coates at the Atlantic. He's been through the city before, producing a substantial piece a few years ago for Time on Wal-Mart's first venture into the city that was admirably attuned to issues of race and class. Now he's reading and liveblogging Arnold Hirsch's Making the Second Ghetto and Beryl Satter's Family Properties (whose publisher pushed back on having "Chicago" in the title because it would put off coastal audiences). They're books I refer back to over and over again. It's interesting to see him react to the city's history, as an outsider at a national publication, and one who brings an interesting perspective—he grew up in an intellectual family in West Baltimore.

Coates began in a post entitled "The Effects of Housing Segregation on Black Wealth" after reading Thomas Sugrue's excellent Sweet Land of Liberty (update: Coates points out that he actually started with Isabel Wilkerson's The Warmth of Other Sons: "Get the book. Read it now. Today is too late.") which gives a broad view of "the forgotten struggle for civil rights in the North," touching on issues that Hirsch and Satter with much greater depth in the city:

Part of keeping power out of black hands is turning the community's aspirational class into a bevy of easy marks. You can only imagine what kind of money was made exploiting the dreams of middle class black people trapped in the ghettos of America. That money represents a transfer of wealth from black hands to white hands. It continued unabated from the early 20th century, through the New Deal (which actually aided this process), well into the 1960s.

Sugrue, in the passage Coates quotes, looks specifically at strict racial segregation in Levittown and Philadelphia, which "created a vast gap between supply and demand. As a result, blacks paid more for housing on average than did whites." Satter's book is about how that happened on the neighborhood level in Chicago, so it has a lot of rich detail about how that was done and its costs to individuals, down to a familial level; it's also a big part of Hirsch's book as well. So a few commenters, including myself, suggested the Hirsch and Satter books; no idea if that influenced his reading list, but he just wrote about Family Properties today. I highly recommend it, but his post is a good introduction:

In finding their way onto the proper side of the divide, Satter's operators hit upon the contract scheme: A speculator would purchase a home at a low price, and then offer it to a black family at a much steeper price. Except no deed would be transferred. The new black "buyer" would be responsible for monthly payments with high interest attached. Moreover, they would be responsible for any repairs and for all code violations. If one payment was missed the contractor would immediately move to evict, and the black "buyer" would forfeit not just their down-payment, but every payment they'd made since, and any money they'd put into upkeep. The speculator would then wash and repeat.

[snip]

Satter estimates that some 85 percent of all properties sold to blacks in Chicago was done on contract.

Combining both Making the Second Ghetto and Family Properties has led Coates to some scorching writing: "Terrorism is Politics By Other Means," "Terrorism and Politics, Clarified," and "The Ghetto is Public Policy."

One thing at least some of the media coverage has mentioned is the city's profound racial segregation, which 40 years ago was almost complete. The history then is an important part of the story today—not just race, but as Coates ably touches on, the nexus of race and wealth—and it's encouraging to see it reaching a national audience.

Related: For a sequel of sorts to Satter and Hirsch, try Blueprint for Disaster or (though I've only read some of this one) Waiting for Gautreaux.