While writing about traffic congestion in Chicago—and the cities in which it's actually worse—I was reminded of an interesting argument about driverless cars, newly legal in California. Will Americans actually take to driverless cars so their hours in them are less wasted, or is the freedom of the open road too powerful?

For the latter, Stuart Staniford:

The vast bulk of spending on cars in the US is for irrational emotional purposes: status display, feelings of safety, etc, not simple transportation…. Just watch a few car ads – endless fantasies of cars driving around on empty roads, barely any discussion of the realistic cost/benefits of sitting in it in stop and go traffic on the 101 or the 495. Thus anywhere from 2/3 to over 95% of the cost of the car is for something other than getting from A to B in reasonable comfort.

I see this in Silicon Valley in spades; parking lots dotted with Mercedes and Porsches well suited to doing 150mph on an empty autobahn or 200mph around a race-track, none of which ever get to do anything of the sort. Maybe occasionally the owner gets a break in the traffic on Highway 1 on a weekend away, but that's about it – maybe half an hour a year that they get to do what the car is actually designed for and the car ads told them it would make them feel good doing. Yet highly accomplished and rational meritocrats will cheerfully stretch the household budget to have one of these things to show off in the driveway or the parking lot at work.

I'm not immune to the pleasures of driving. One of the most fun things I've ever gotten to do was drive a stick-shift BMW on empty country roads in the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas, followed by getting a massive old Lincoln Continental up to 110 on the straightaways of those same roads. Driving can be really, really fun. It's just rarely fun. (I learned to drive on an Aerostar and a Geo Metro; I know the depths to which driving can sink.) The myth of the open road usually gets exploded because the roads aren't actually open; much as I can appreciate the experience of driving a fast car, I shake my head when someone in a six-figure sports car floors it on a green light downtown and then comes to a screeching halt 100 yards later at the next light.

Which is why I tend to agree with Porsche owner Kevin Drum on this:

Sure, lots of people buy cars as status symbols. But lots of people don't. Honest. At a guess, I'd say that at least half of all drivers basically just buy transportation and don't actually care much about cars as status symbols. And half is a lot.

Most people can't, unless they have a cheap car with good bones that they can improve and maintain. The rule of thumb seems to be 10-30 percent of your annual income for a car; there just aren't enough people making six figures to support that many status symbols.

Even among the status obsessed—or, more accurately, especially among the status obsessed—time is the most precious commodity. Driverless cars will appeal to the well-off because they'll allow them to be workaholics for an hour or two a day formerly dedicated to driving. And I suspect that once you stop actively driving a car, you'll start to view it as much less of a status symbol.

It's a combination of conspicuous leisure with the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism: Veblen and Weber! How can it not be a hit?

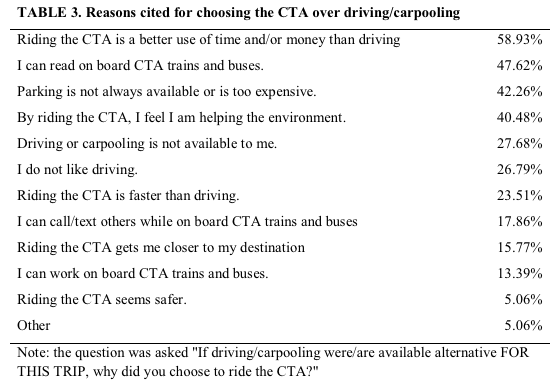

A study by two Northwestern researchers actually looked into leisure time on the CTA. It's a small sample and part of it is a Web survey, so YMMV, but (PDF):

Not a lot of work is getting done, but working on the CTA is actually hard—no one wants to take a work call from someone on a bus or El train, and there's no room for a terrifically multi-function device. A car's a much better place to get business work done. (Unless you get carsick from reading in a car, like my wife; that, I think, is the worst audience for driverless cars, because driving is at least something to do.)

The best audience, meanwhile, is the elderly. The suburbs are getting old fast (PDF):

Since 1970, the proportion of older suburban dwellers has been steadily increasing, while the proportion of those living in central cities has been decreasing (4). Today, approximately 75 percent of people over age 65 live in suburban or rural locations. Residents of suburban areas have few transportation options other than the automobile. When older residents of suburbs cannot drive, they rely on others with cars, or they walk, and only rarely use public transit (5). In 1990, only 1 to 3 percent of trips taken by people over age 65 in the United States were made on public transit and 6 to 10 percent of trips were made by walking (6). In contrast, the vast majority of trips were by private vehicle with the older person as the driver or the passenger (6).

That's 1999 data, but the trend doesn't seem to be abating; the numbers don't seem to have changed at all, which is why planners are worried about what suburbs will do with lots of residents outliving their driving age. Boomers just started turning 65. The number of elderly drivers on the road is about to jump:

The reality is there are more than 20 million drivers age 70 and older on the roads today, compared with 18 million in 1997, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. In Illinois, more than 796,000 residents over 70 have licenses, including one 106-year-old man, according to the secretary of state's office.

The oldest baby boomers will turn 65 next year, the start of an explosion of elderly drivers. By 2030, motorists 65 and older are projected to reach 57 million, according to the Government Accountability Office.

The elderly are also getting in fewer fatal crashes, for interesting reasons:

Despite the growing numbers, fewer seniors were involved in fatal collisions during 1997-2006 than in years past, according to a 2008 insurance institute study. More seniors are self-regulating, avoiding rush hour or night driving. And the health of seniors — which some experts say is more critical to driving skill than age — is improving dramatically.

It's a lot of people who are going to want to drive less, but will still have a need to get around, and are often nowhere near public transportation. Transportation and consumer goods have followed the Boomers' path for more than half a century; if they embrace driverless cars, we could follow them there as well.

Photograph: jurvetson (CC by 2.0)