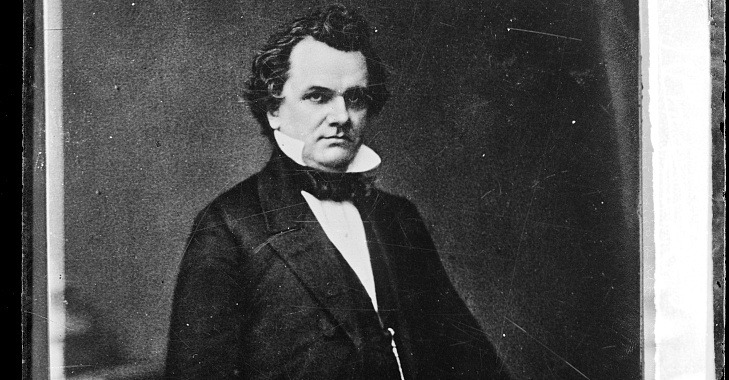

Stephen Douglas is not too popular in Illinois these days. Last year, the city added an ‘s’ to Douglass Park on the West Side, renaming it after abolitionist Frederick Douglass and his wife, Anna. In Springfield, then-House Speaker Michael Madigan ordered the removal of Douglas’s statue from the capitol grounds, and his portrait from the House chamber, where it had hung on the Democratic side for more than a century, across the aisle from Abraham Lincoln’s. Even Dick Durbin, who holds Douglas’s old Senate seat, tweeted “Removing Stephen Douglas’ statue from the main grounds of the State Capitol, and replacing it with Dr. Martin Luther King’s, is the right thing to do.”

Douglas’s offenses? He inherited a Mississippi plantation, and 100 slaves, from his wife. During his campaigns for the Senate and the presidency, he employed “abhorrent words towards people of color,” according to Madigan. (Yes, the worst one.)

Douglas is best remembered today as Lincoln’s foil in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates, defending white supremacy and the right to own slaves, while Lincoln argued for racial equality and the right to free labor. That’s not inaccurate, but neither is it all of Douglas’s legacy, especially in Chicago. Douglas, who settled here after he was elected to the Senate in 1847, may have been the most important political figure in the city’s history.

As soon as Douglas arrived in Chicago, he began envisioning the city as the nation’s railroad hub, where the manufactured goods of the East would be exchanged for the foodstuffs of Western farmers—a marketplace uniting the commercial interests of the Atlantic Ocean, the Great Lakes, the Gulf of Mexico, and someday soon, he hoped, the Pacific. To further that vision, he passed the Illinois Central Railroad Tax Act, which created what was then the world’s longest rail line, stretching from Cairo, at the southern end of the state, to Galena, in its northwest extremity, with a spur connecting Chicago.

To Douglas, railroads were not simply a means of transportation, for conveying passengers and products. They bound together the Union, tie by tie, track by track—a Union essential for building Douglas’s Young America, a dynamic nation that would fill in all the lands from coast to coast. In the five years after the Illinois Central began running, the population of Chicago tripled, from 28,260 to 80,028. In the 1850s, the nation’s railroad mileage would also triple, from 9,000 to 30,000; 2,500 miles of those tracks were in Illinois, the decade’s fastest-growing state, since nearly every line west of Lake Michigan terminated in Chicago.

A young Illinois Central executive described the burgeoning city’s energy in a letter to his boss, in prose that prefigured Carl Sandburg’s poetic tribute: “There were about half a dozen locomotives flying about whistling, screaming, puffing, blowing, backing and going ahead, five or six hundred teams of every description loading and unloading; two or three or four… buildings going up skyward at the rate of a loft a day—hammers banging, tin rattling, chisels clinking and men swarming on what is the handsomest passenger station in the country – immense loads of round hogs coming over from neighboring depots and not less than 50 cars of live ones standing here and there on the track; merchandise of every description scattered around; emigrants crowding everywhere, passengers running about.”

(The Illinois Central was not just profitable for Chicago, it was profitable for Douglas, too: shortly after moving to the city, he began buying up lakefront property, sixteen acres of which he sold to the new railroad for $21,320.)

Once the railroad overtook the steamboat as the fastest method of transportation through the wilderness, Chicago replaced St. Louis as the Gateway to the West. St. Louis attempted to retain that title by promoting itself as the terminus of a transcontinental railroad, but Douglas argued that there should be a terminus in Chicago. Douglas’s argument prevailed—one reason Chicago, not St. Louis, is today the Midwest’s dominant city.

Douglas’s desire for a transcontinental railroad also inspired his greatest legislative fiasco, which has come to define his legacy more than the railroad itself. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, which Douglas authored and sponsored, is remembered as a scheme for opening the territories to slavery. In fact, it was Douglas’s scheme for overcoming Southern opposition to a railroad that would follow a Northern route to the Pacific—a route that would, of course, embark from Chicago, and run through Nebraska Territory, which had been designated as free soil by the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

Ever the hometown booster, Douglas acceded to Southern demands that he blow up the Missouri Compromise, and make it possible for Nebraska settlers, attracted by the railroad, to own slaves. Douglas had hoped to sweep aside the “slavery agitation” standing in the way of a railroad that would bring even more traffic to Chicago, and further bind together his beloved Union. Instead, the Act inflamed sectional controversies over slavery, and revived the political career of former one-term congressman Abraham Lincoln, whose 1854 speech at Peoria about slavery and the Kansas-Nebraska Act is a turning point in his career and the history of the country. Six years later, Lincoln would defeat Douglas in the presidential election.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act has been blamed for hastening the Civil War, and it’s certainly a stain on Douglas’s historic reputation. When the railroad was completed in 1869, though, it followed the northern route Douglas had championed. Between the pounding of the golden spike and the turn of the century, Chicago’s population increased five-fold.

Douglas died in 1861, shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War. He is buried beneath a 96-foot-tall column on 35th Street, in the Douglas community area, which bears his name. Three local state representatives proposed tearing down the monument, while leaving Douglas’s grave intact, but so far, his tomb appears safe: it does not appear on Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s list of 41 controversial monuments.

Douglas should be remembered as the quintessential Illinois politician: he was a dealmaker, not an idealist, willing to tolerate the expansion of slavery in exchange for advancing his adopted hometown’s economic prospects. As the father of the Illinois Central Railroad, and the founder of the state’s Democratic machine, he actually contributed far more to Illinois’s development and culture than Lincoln did. Douglas’s political machinations put him on the wrong side of history, though, which is why so many of his honors did not survive 2020’s reckoning over racial justice.

Comments are closed.