Yesterday as I was reading up on Martin Luther King and racial tensions in Chicago from World War II through the mid-'60s, I thought back to one of the more amazing old Tribune series I've come across—a multipart exploration of Uptown and the poor Appalachian whites who moved there en masse during and after WWII (there's not much of an obvious legacy left, but the fine country-and-western bar Carol's is one remnant, located in what used to be the most Appalachian census district in the city).

Arnold Hirsh and other writers attribute a great deal of the post-war racial violence to the Great Migration—a massive influx of Southern blacks in a short period of time. That the new Chicagoans were black is obviously significant, but not to be underestimated is the fact that they were Southern. And the white Southerners who arrived at the same time provide a useful contrast, not least because they came to Chicago and other Midwestern cities—like Akron, the "capital of West Virginia"—along the Hillbilly Highway for similar reasons: the economy of the already-poor central and southern Appalachians was exacerbated by the increasing automation of the coal industry, forcing migrants already uprooted by the war to seek blue-collar jobs in more thriving industrial areas.

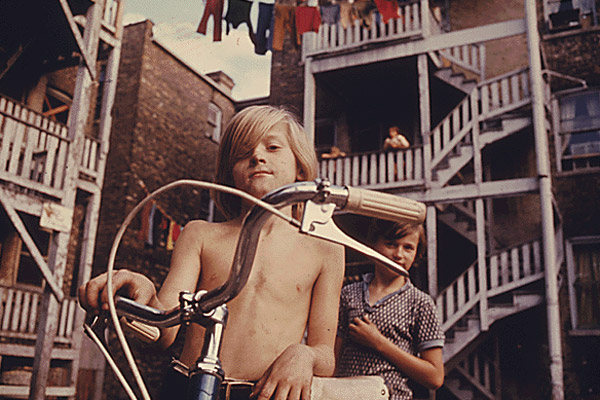

During the 1950s, the Tribune dispatched tough, oddball investigative reporter and Radcliffe grad Norma Lee Browning to Uptown for a series beginning with "Girl Reporter Visits Jungles of Hillbillies." The language Browning used to describe the city's white Southern migrants was, um, resonant:

Most authorities rate them at the bottom of the heap, socially, morally, mentally—and at the top of those migrant "undesirables" contributing to the city's increased crime rate.

"The average Chicagoan doesn't realize it, but it isn't our own people committing the crimes—it's the migrants taking over, forcing our own long time residents to move out," said Lt. Michael Delaney, head of the police juvenile section.

[snip]

"It's a dangerous situation, one that we have to wake up to and face. These migrants are United States citizens, free to roam anywhere they wish. But they have turned the streets of Chicago into a lawless free-for-all with their primitive jungle tactics" [said Walter Devereux, chief investigator for the Chicago Crime commission].

Authorities are reluctant to point a finger at any one segment of the population or nationality group, but they agree that the southern hillbilly migrants, who have descended on Chicago like a plague of locusts in the last few years, have the lowest standard of living and moral code [if any] of all, the biggest capacity for liquor, and the most savage and vicious tactics when drunk, which is most of the time.

Other than getting "our own people" off the hook, however, they're reluctant to point a finger.

The hillbillies' home and family life, experienced investigators say, is the most depraved of any they have ever encountered, with no understanding of sanitation or health. They get married one day, unmarried the next, and in the confusion of common law marriages many children never know who their parents are—and nobody cares.

Child brides are still the rule rather than the exception. Of 400 rape cases recently investigated by juvenile police, the majority involved migrants who didn't even know what the word meant. Their own hill country mores, which they brought with them to Chicago, includes living with 13 and 14 year old girls.

Continuing to not point the finger, the authorities went on:

Authorities agree that while other troublesome transients have contributed their share toward the city's crime and delinquency rate, no other group is so completely devoid of self-pride and responsibility as the southern migrants. Others at least spend part of their wages on clothes and furniture, trying to maintain the semblance of a home.

This was directly contradictory to one of Browning's observations—clearly, the troublesome transients did spend money on clothes:

The women wear blue jeans, slacks [preferably red plaid] or cheesy brocade and spangles. Men are in work pants, coveralls, leather motorcycle jackets, and Presley sideburns. [In some 30 joints we only saw one "square" in a suit.]

In her second article, "New 'Breed' of Migrants City Problem," Browning outlined one of the problems:

They're American-born white skinned natives, with no racial, religious, or language characteristics [except southern accents] to set them apart as an ethnic group.

Yet as a group [steadily increasing] with specific, recognizable culture patterns that are completely alien to urban life, they pose one of the most serious problems in Chicago's projected plans for industrial expansion.

And further explained the "hillbilly problem":

It includes "disgraceful" conditions, particularly in community toilets and kitchens, "mixed-up" families of in-laws, cousins, children, and adults all living together, frequent moving, skipping out on the rent, a primitive conception of sanitation, resistance to public health measures, immunization, and education.

But Chicago's hillbillies didn't have sufficient lack of self-pride to take Browning's articles lying down. The day after Browning's second article ran in the Tribune, she got a letter from the husband of a former Tribune employee who was none too happy with her portrayal of his people, one of two critical letters the paper printed:

We came to Chicago seven years ago. I went to work in an engineering office and am still there. My wife worked for your paper, and is now employed in a leading manufacturing company office. We attend church and Sunday school, and live in the same apartment we rented when we came here.

Anyone with nerve enough to blame "hillbillies" for all the evils of Chicago, as Miss Browning did in today's article, needs a keeper in a white jacket rather than a bodyguard. Just as not all native Chicagoans are gangsters, neither are we all saloon patrons and skid row inhabitants.

A few days later, Browning and the Tribune kicked off a new series that practically tripped all over itself in its hasty backpedaling, beginning with the impressively condescending "Charges Upset Feudin' Brand of Hillbillies":

Chicago's feudin' and fightin'-mad hillbillies are ready to rip this damn yankee town to pieces following published statements of city officials and citizens' committes that the city is confronted with a "hillbilly problem.

The lesson: don't anger a hillbilly. He'll up and write letters. Browning followed with "Better Smile if You Tag This Couple as Hillbillies: From Arkansas, 2 Resent Term"; "Northern Wife Resents Southern Mate Being Called Hillbilly: Calls Him Honest and Diligent"; "A Lot of Solid Citizens from South Resent 'Hillbilly' Tag: Cite Record Since Coming North."

Browning and her editors had softened, and in "Virginia Couple Finds Chicago a Cold and Lonesome Place," Browning profiled a family from my hometown of Roanoke that was caught in the underside of the postwar boom and the shift of industry to the south in search of non-union labor:

Why did the Devinney's come to Chicago? For the same reason a lot of others are coming—because they couldn't make a living down south.

Devinny's father died when he was 3 years old, and the boy quit school after the seventh grade to help raise the family of four other brothers and a sister.

He spent three years overseas during the war, was married in 1950, and went to work for a manufacturer of storm windows in Roanoke. The job lasted five years—until the company was forced out of business by northern corporations that moved in.

"It's the same thing that's happened all over the south," they said. "Factories from the north moved south and expect the southerners to work for less than a dollar an hour [less than $8.05 in 2011 dollars]. Can you live on that? If southern people are not educated enough for employment in these factories, they are turned away."

With only a seventh grade education Devinney walked the streets day and night looking for work, and finally, in danger of soon losing his home, came to Chicago to take a refrigeration and air conditioning course.

He didn't finish it. His wife, who had stayed in Roanoke, became ill, needed major surgery, and he went back to be with her. The debts piled up. They sold their furniture, rented their house, and came back to Chicago.

For the eighty-some dollars a month the Devinneys paid in rent, they got a "substandard fire-trap" in a "dingy, odoriferous, bleak building" at the same price as the payments on their five-room house in Roanoke. Roy Devinney planned on restarting his education, as soon as they paid off their debt.

The socioeconomic issues of black Southerners and white Appalachians long paralleled each other during the 20th century, and the 21st. I was reminded of this during the recent spate of news about TV chef Paula Deen and her diagnosis with diabetes, which brought up some uncomfortable questions of culture, class, and public health well-summarized in this post. When that news broke, I went back to the Centers for Disease Control's map of the "diabetes belt," one of the more fascinating public-health visualizations I've seen in recent years. Diabetes is often correlated with soul food, but the diabetes belt runs north along the spine of the Appalachians into Kentucky and West Virginia, which have some of the more severe public-health problems in the country: Clay County, Kentucky, for example, long one of the poorest counties in America, where the obesity rate is estimated to be twice the national average, or Huntington, West Virginia, where celebrity chef Jaimie Oliver moved in to try to reform its obesity, heart disease, and diabetes rates.

(Side note: regarding the "diabetes belt," one of the more interesting details is how western Virginia and North Carolina fare better than West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and eastern Tennessee. I've long thought there's a lot of hay to be made in state-level comparisons of public-policy outcomes in central Appalachia, but it's not something I've seen much research on.)

In an urban setting, the status of white Appalachians during the Great Migration provide an interesting counterpoint to that of African-Americans in northern and western cities during the same era. If race was the primary driver of cultural conflict during the critical postwar years, it wasn't the only one, as white Southerners of not-dissimilar socioeconomic extraction were equally reviled by the powers that be, if not as much or as long by the community at large. It adds an important texture to the struggles of postwar Chicago, underlining how class, regionalism, and culture overlapped with and amplified the ever-present tensions of race during the civil-rights years.

Comments are closed.