Thanks to Eric Zorn, I just read "The Dark Side of Mitt Romney," an excerpt from the book The Real Romney in Vanity Fair. (Unsurprisingly, it's less like the "dark" side than the "stiffly unlikeable side.") Inevitably, it turns to Bain Capital and venture/vulture capitalism, which is the political topic of the week—from both the right and the left—and, finally, an actually interesting line of attack based on some of the most important questions about markets and capitalism in the 21st century.

The attacks on Romney have largely focused on job destruction versus job creation in the realm of private equity. Along those lines, there's actually a great deal of research, much of it coming out of the University of Chicago. At The Atlantic, Jordan Weissman has a good rundown of the studies:

The reality, as illustrated in a 2011 study from researchers at the University of Chicago, Harvard, and the U.S. Census Bureau, is more complicated. The paper examined what happened to workers at 3,200 companies targeted in private equity acquisitions between 1980 and 2005. Companies did tend to fire more workers in the years after a buyout compared to competitors in their industry. But they also tended to hire more new workers. They also were more likely to sell off divisions or buy up new ones. As a result, companies involved in a private equity deal saw much, much more turnover — or "job reallocation" as the academics put it — but only a net decrease in employment of about 1% compared to other businesses.

And it's even more complicated than that:

1. The establishments of target firms that exist at the time of the transaction exhibit lower rates of net employment growth in the years before, of, and immediately after a private equity transaction, when compared with a group of similar control establishments.

2. In the second and third years after such transactions, these targets have considerably lower net job growth than control establishments.

3. By the fourth and fifth years, job growth of the target firms is slightly above that of the controls.

4. Target establishments seem to create roughly as many jobs as similar control establishments. The lower net job growth of about 10% over the five years after the transaction appears to be generated via higher gross job destruction as the new private equity-backed owners shed presumably unprofitable segments of the target firms.

5. These patterns are exclusively confined to Retail Trade, Services and Financial Services: there is little difference in the post-transaction growth of the target firms in Manufacturing.

In short, according to the authors, private equity firms do cost jobs, but only in certain segments. But cutting isn't all private equity firms do, the authors write:

Overall, the results in Table 3 strongly show that target firms are undergoing much more restructuring than we observe at similar non-target control firms. These results suggest that the employment impact of private equity buyouts is much more complex than may be widely understood. While, on net, we find slower employment growth associated with private equity transactions, we also find substantial greenfield entry and acquisition of establishments by target firms postbuyout. This is indicative of substantial investments in and commitments to the continued operation and success of the target firms by private equity firms.

The Los Angeles Times, which has looked extensively into Romney's record at Bain Capital, gives the example of AxleTech, a Troy, Michigan-based manufacturer with a location in Chicago. Its former private-equity sugar daddy, the powerful Washington firm The Carlyle Group, brags about its "Key Value Creation Metrics" in its case study (PDF):

* Tripled AxleTech’s level of capital spending in new machinery and facility expansion, resulting in a doubling of worldwide production.

This is the other side of private equity that hasn't gotten as much attention in the flap over Romney and Bain: that the job of the likely GOP nominee for president wasn't just finding efficiencies in troubled companies; it was the targeted use of debt financing to expand at critical times.

Asked in an interview about Bain's bankruptcy and failure rate, Mr. Romney said that in buyout deals, "our orientation was by and large to acquire businesses that were out of favor and in some cases in trouble." He added that Bain wasn't the type of firm that stripped companies and fired workers, but instead, "our approach was to try to build a business. We were not always successful."

Romney built his career not just on "creative destruction," but on debt—the central financial issue for individuals, companies, and governments in the coming election and the years to come. Call it "private equity" or "leveraged buyouts" or whatever you want: he's an expert in the use (or abuse) of debt, and it's a potentially awkward, potentially intriguing fit in his role as GOP standard-bearer.

Related: My favorite bit of that Wall Street Journal investigation into the successes and failures of Bain Capital is this:

Mr. Romney had a particularly close involvement with one firm that flamed out, a maker of children's dolls meant to resemble their owners.

Gosh, if only there was some kind of PowerPoint-friendly chart to demonstrate why that's a terrible business idea.

Update: Here's a good example from Paul Krugman of the potential overlap between what Romney did at Bain Capital and what the government should or shouldn't do now.

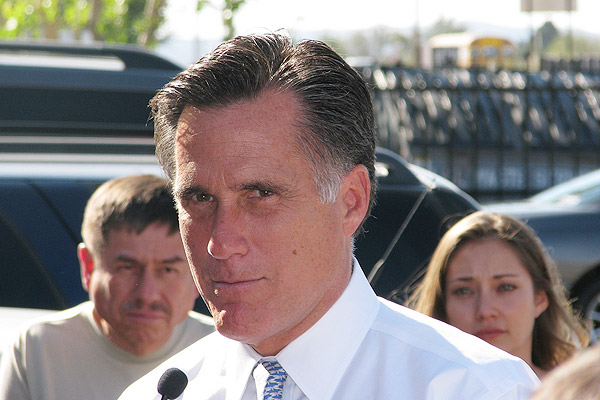

Photograph: nmfbihop (CC by 2.0)