I finally got around to seeing Lincoln yesterday, a surprisingly long time for me to wait to see a drama about congressional politics. Its meaning for contemporary audiences has inevitably been kicked about a bit. Ta-Nehisi Coates, for instance:

Lincoln says the Civil War is about slavery. Full Stop. No mealy-mouthed "brother against brother" nonsense. No vague whining about tragedy. Slavery is the tragedy. No homilies to states rights. The right at stake is the right to enslave. And the black people doing the killing and dying are not confused. Nor are the authors of the Confederacy. I have never seen these facts—basic history though they may—stated so forthrightly, without apology, in the sphere of mass popular culture.

I'd push it even farther than that: it says the Civil War is not just about slavery, but that it's about slavery as the economic foundation of the South, particularly in a crucial scene near the end of the movie, when Jackie Earl Haley, bringing a simmering malevolance to Confederate vice-president Alexander Stephens, addresses Lincoln. Roy Edroso captures it:

Stephens (previously shown in a meeting with black Union officers to be smarter than his comrades) tells the President that the war will end not only slavery but the South's way of life. Stephens shows no obvious outrage over this, nor regret, though we may assume he has felt both. Here Spielberg does something that struck me as significant; he photographs the already strange-looking Haley in an unflattering light that makes him seem slightly deformed. I imagine the idea was not to dehumanize him in the usual sense of undercutting his argument by making him look bad, but to suggest that he represents a literally alien species, and that he is aware that it is passing from existence.

What Stephens says (PDF) is that the Constitution "now extinguishes slavery. And with it our economy…. All our traditions will be obliterated. We won't know ourselves anymore." In an earlier scene, Lincoln explains that economic power structure to a border-state couple: "Slavery troubled me, as long as I can remember, in a way it never troubled my father, though he hated it. In his own fashion. He knew no smallholding dirt farmer could compete with slave plantations. He took us out from Kentucky to get away from ‘em."

In that, it's quite interesting; a corrective, A.O. Scott points out, to "just about every other movie made about the War." But that's the present as the-past-is-never-really-past.

What I saw briefly but not trivially in Lincoln about the present and the future, though perhaps I'm reading too much into it based on screenwriter Tony Kushner's sexual orientation, were some nudges on gay marriage. The arguable climax of the movie has hardline abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens taking the bill enshrining the 13th Amendment from the floor of the House and home to his biracial common-law wife, with whom he shares a bed. It pushes the relationship between Stevens and Lydia Hamilton Smith beyond what historians know, and then sharpens it to a point.

Or perhaps it was because I saw it immediately after eavesdropping on a first date (it sounded like one, at least) of an interracial gay couple (maybe not a couple, but if it was a first date, it seemed to be going okay), who spent some of the conversation talking about race, sexual orientation, discrimination, and their parallels. It was impossible not to leave it at the ticket lobby. But I don't think it was entirely a matter of what I happened to hear over pie:

Kushner also said he felt that Obama’s decision to express support for gay marriage was “very Lincolnian.” He said, “I think it was handled with absolute strategic and moral perfection. It arrived at exactly the right moment. As my husband said to him tonight, it was a life-changing moment when the president of the U.S. said that.”

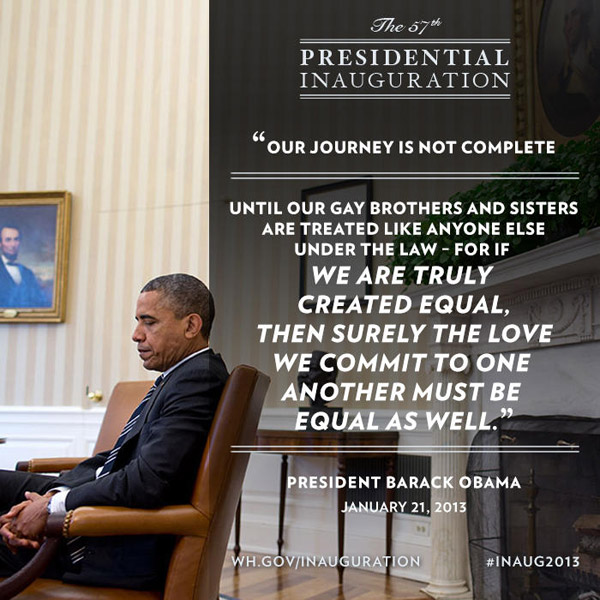

Then President Obama gave his inaugural address today and the movie folded back in on real life.

Much of the drama in Lincoln is about the use of political rhetoric: what can and cannot be said at a time and place in history in order to move it forward. Stevens is pressed by the fictional radical Asa Vintner Litton to speak for racial equality (an anachronistic phrase), and by his colleague James Ashley to focus on legal equality. At a crucial juncture, Stevens tells the House:

Today Barack Obama, in what veteran correspondent James Fallows calls the "most sustainedly 'progressive' statement Barack Obama has made in his decade on the national stage," said this (as tweeted by the White House):

Back to the movie:

From one perspective, it's surprising to hear the President of the United States string together "Seneca Falls, and Selma, and Stonewall." From another, it's surprising to hear Kushner call Barack Obama's embrace of gay marriage—an evolution of his beliefs hurried along by his vice president several months before he was re-elected—"absolute strategic and moral perfection" arriving "at exactly the right moment." It's progressive, though not radical, a distinction that for presidents is a matter of timing.

Photograph: The White House