Well, it's not quite a year, but it's close: 326 days without an inch of snow, a record. It's been the least snowy season in recorded history, and warm (my favorite new phrase: "temperature surplus").

In some ways it's good. The city's likely to save millions, but the lack of snow is so unprecedented that we don't know how much we'll save. And my colleague Jeff Ruby contends that it's good for Chicagoans, who secretly hate winter, even if they act otherwise:

Chicagoans are hardwired to accept—nay, welcome—an extended arctic interval so hostile that the rest of the world would likely consider it punishment. But let’s be honest: Our attitude toward the nadir of winter is not love or even resignation. It is fear. Fear that we will be exposed as ordinary people who, beneath the civic chest thumping, dread the dehumanizing grind of cold weather.

[An aside: I want to clear up something about my home state: "'Chicago knows how to handle winter,' says Rob Lentini, a former Evanstonian who now lives on the Atlantic Coast. 'Other places, which won’t be mentioned—Virginia!—collapse into a fetal position when it snows.'" In most of the state, we curl up into a fetal position because when it snows, you can't actually go anywhere. I grew up on a rural route with an steep uphill S-curve on one side of the house and an big C-curve on the other, and being out in the country, it took awhile for it to get plowed. One of the sights that most amazed me when I moved here was watching the scrapers get out ahead of a coming snow. It's D.C. that doesn't know what it's doing.]

I respectfully disagree. I'm reminded of one of my favorite essays about Chicago, Brent Staples's "Mr. Bellow's Planet" (which I wrote about at some length awhile back). It captures the Hyde Park experience perfectly—especially the part that begins with "a journal of Chicago is a journal of weather":

In deepest winter, arctic windsd dipped down from Canada and froze every bit of moisture from the air. Indoors the air was so dry that it split your lips and gave you nosebleeds. The cold slipped its knife through the bathroom window and cut you as you showered. Outside, the storm drains along the street vented steam, as though boiling. As you walked from the corner store, steam flared from your tearducts and from the surface of the eye itself.

The beauty of the nights compensated for this cruelty. The wind that punished had also swept the sky clean and left it breathtakingly clear.

The first time I came to Chicago was during a cold, dry winter; we amused ourselves by shuffling around the hotel in sock feet and giving ourselves explosive static shocks.

What everyone I know who came to Chicago from someplace else dislikes most about the city is the absence of natural majesty. New York and Los Angeles have their own physical beauty; Chicago had to build the beauty it needed, which may account for its skyline and architecture, and its dogged protection of the lakefront. Even its natural advantages, from a coldly economic sense, are humble in comparison to its worldly peers, as William Cronon writes in Nature's Metropolis:

The Chicago River may have been more than a puny brook, but it was rather less than a great waterway: short, shallow, with no current to speak of, and far better suited to canoes than to sailing ships. A visitor in 1848 called it "a sluggish, slimy stream, too lazy to clean itself." It nonetheless had two great virtues. One was its harbor: bad as it might be, it was still the best available on the southern shore of Lake Michigan in the 250 miles between St. Joseph, Michigan, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The writer Caroline Kirkland was only slightly exaggerating when she called it "the best harbor on Lake Michigan" and the "worst harbor and smallest river any great commercial city ever lived on."

Chicago: it'll do.

What the winter gives us is awe. Not toughness or bragging rights, given how often so many of us fail at living heartily through it, especially as it plods slowly through February and March. "In Chicago I learned that the weather made me who I was," writes Staples. "The mood was impenetrable. I didn't know it was a mood until the sun came shining to the rescue. The lesson was new each time."

The Hawk Wind is our Santa Anas—the Red Wind, in Raymond Chandler's phrase: "It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands' necks. Anything can happen." Joan Didion explored it further in an essay on the phenomenon:

It is hard for people who have not lived in Los Angeles to realize how radically the Santa Ana figures in the local imagination. The city burning is Los Angeles’s deepest image of itself…. [J]ust as the reliably long and bitter winters of New England determine the way life is lived there, so the violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability. The winds shows us how close to the edge we are.

Our deepest image of Chicago is not fire, but ice. It's a difficult mercy; in a violent city, it puts the fires out.

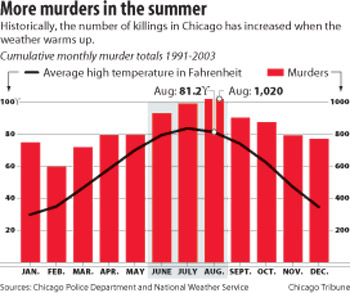

I'm not surprised that murders are lower in February and March than January. People make it through January. February and March are when winter finally breaks people. Everything is lessened: the sounds, the traffic, the violence. Chicago reversed a river and raised the city above a swamp, to exist; the winter is when nature bends back. It's an uneasy, ambivalent awe, but it's the awe that we have, and it makes us who we are.

Photograph: remove (CC by 2.0)