One of the ongoing complaints about Illinois's tax system—besides general complaints about it being too high for everything—is its prairie flatness, which is unusual among states. One complaint is that it hits low-income taxpayers hardest (Naomi Jakobsson, D-Urbana, has proposed a graduated tax); the other is that a flat tax costs the state revenues as income inequality grows:

We recently highlighted the results of a survey from the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute that found a majority of people in the Prairie State support a progressive income tax to raise sorely needed state revenue. A recent legislative analysis found that if households earning more than $250,000 a year were taxed at a national standard of 6 percent (rather than the current flat rate of 3 percent), the state would collect an additional $3 billion a year.

(Now, of course, it's up to five percent across the board; the flat tax is enshrined in the state's constitution.)

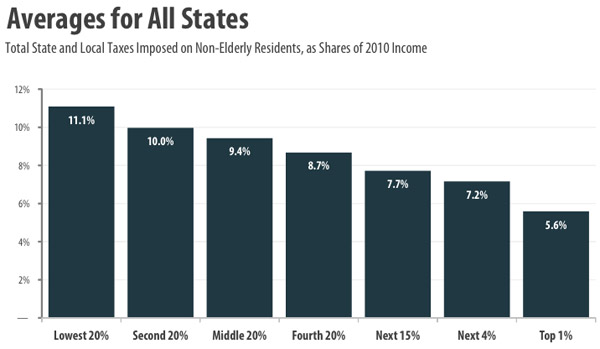

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy just ran the numbers on state taxation in the U.S., and it's little surprise, given the state's tax structure, that it's comparatively regressive, coming in at fourth in the country. Let's start with the national averages:

That's all taxes, or all the big ones: income, sales, and property. Now, here are the ten most regressive states:

.jpg)

Illinois taxes the poorest 20 percent of its residents at a higher level than the national average; it's one of the few states above 13 percent, 2.7 percent above the national average.

It's above average for the middle class, as well: the national average for the middle 60 percent is 9.4 percent, so Illinois is 1.7 percent above the national average. Only Arkansas (11.2 percent), Hawaii (11.3 percent), and New York (11.2 percent) tax the middle class at higher rates than Illinois.

As you go up the tax bracket, the effective state and local tax rate falls, but it remains relatively high. Illinois taxes the top 80-95 percent of residents at nine percent, behind only Arkansas and Connecticut (just barely), Wisconsin (9.7 percent), and New York (11 percent), and 1.3 percent above the national average. The 95-99 percent income bracket gets hit at 7.6 percent, just a bit above the national average of 7.2 percent.

Only on the top one percent does Illinois fall below the national average: 4.9 percent compared to 5.6 percent.

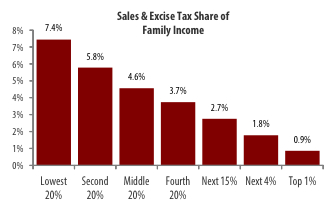

But according to the ITEP report, it's not the flat tax doing most of the damage (NB: ITEP uses the 3.75 income tax rate scheduled for 2015, not the current five percent rate), in part because the state increased its earned-income tax credit from five to ten percent. The big one is sales taxes. Illinois has a pretty high state sales tax (though it has exemptions for food and drugs), ranking tenth in the country if you factor in state and local sales taxes. And sales taxes are regressive.

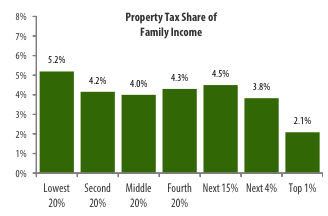

But it's not just the sales tax. Another complaint about Illinois's tax system is its dependence on property taxes (PDF): "Historically, local governments in Illinois have been more dependent on local property taxes than are local governments in other states." Illinois property taxes generated 36.3% of local government revenue, which exceeded the national average of 27.9%." This is one of the issues with the downstate pension shift; far-downstate counties tend to have lower property values, and thus lower revenues than the collar counties.

Illinois's property taxes as a share of income—which includes property taxes passed on as rent—is one of the highest in the country. Connecticut's is higher on the very poor and the middle class; New York's is higher on the very poor; Vermont is higher on the lower-middle and very-middle classes; New Hampshire and New Jersey are higher across the board. But all those states have progressive income taxes but New Hampshire, which has no income tax and a much lower sales-tax burden.

The report also has some little bonuses scattered throughout, one of which touches on another aspect of the state's tax system that's been kicked around: taxes on services. Illinois has fairly high sales taxes, but it has a narrow base, since few services are taxed. Hawaii is tops, taxing 160 different services as of 2007; Illinois is near the bottom, with less than 20, just ahead of Colorado and New Hampshire (Alaska and Oregon don't tax services). The state's COGFA has found that $7 billion could be raised by expanding the state's taxation of services.