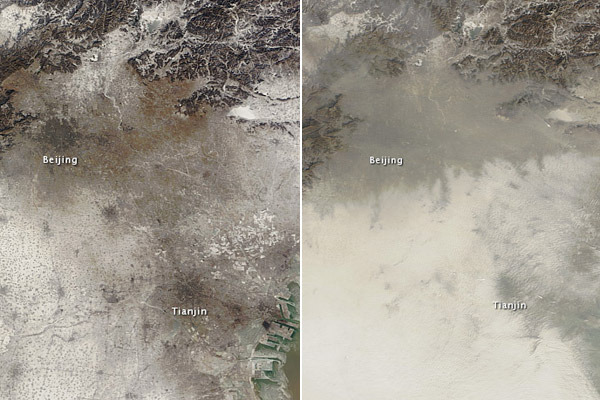

Beijing, January 3 (left); Beijing, January 14 (right)

Right now, when I type "Beijing" into Google, the first result is "Beijing smog." This is what it looks like ("on Saturday, the sun was completely blocked by this thick layer of toxic air").

In the 24-hour period up to 10 a.m. Sunday, it said 18 of the hourly readings were "beyond index." The highest number was 755, which corresponded to a PM2.5 density of 886 micrograms per cubic meter. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's air quality index goes up to only 500, and the agency advises that anything greater than 300 would trigger a health warning of "emergency conditions," with the entire population likely affected.

At the Atlantic, Alexis Madrigal cautions those who'd ask "why don't they do something about it" to look at America—"it took American activists over a century to win the precise same battle"—and in particular Chicago (an early pioneer in air quality, with the first civic air quality ordinance passed in 1881). And Chicago was regularly devoured by smoke monsters for much of the 20th century. Here's what we know about early, smoggy, Chicago, other than the fact that it was really bad (PDF).

Smoky days in these cities were characterized by a combination of coarse soot and dust fall with fine carbonaceous and acidic particles and gases from industrial and domestic sources. Limited data suggest ambient particle levels in Chicago, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh in the 1910s were on the order of 1000–10,000 µ g/m3 , with dust fall levels in Pittsburgh of 1000 t/mi2. Episodes would frequently blot out the sun, requiring gaslights at midday in Pittsburgh, which contemporaries noted was “a smoky dismal city at her best.”

Another source (PDF) gives Chicago's high TSP (total suspended particulate) measurement in 1913, a century ago, as 9.3 mg/m3, or 9,300 micrograms per cubic meter.

[Update: to clarify, that's the highest level recorded; "typical values ranged from 0.3-2.0 mg/m3."]

But that doesn't mean Chicago's air was ten times as bad as Beijing's was now. Beijing's air quality is measured above in PM2.5, particulate matter that's 2.5 micrometers or smaller; TSP is an older measurement that larger particles (including dust and pollen), and the size of particulate matter that the EPA uses to determine air quality has been declining as we learn more about the dangers of fine, manmade particles.

If my math is right, using a conversion factor of 0.53 taken from an average here (PDF; the ratio of TSP to PM2.5 isn't always the same, so it's very rough), Chicago's air in 1913, at its worst, would have been about five times worse. Using a different set of numbers (PDF), it'd be about 30 percent, which would make Chicago's air three or four times worse.

Either way, it was horrifically bad. Cities slowly cracked down, but really stepped up the pace 1960s and early 1970s. In 1969, the city with the worst air pollution in the country was Chattanooga, which had air quality comparable to Beijing (which usually has better air quality than this month's freakish levels):

The established federal standard for acceptable TSP is 75 micrograms per cubic meter of air [in 1990]; Chattanooga averaged 214 micrograms in 1969. There were days when the TSP count climbed into the thousands, and sometimes filters in the monitoring equipment got so clogged it broke down.

The air was so bad it melted nylon stockings on women's legs. But in a decade, thanks to strict environmental regulations and the sacking of a heavily polluting Department of Defense plant, the average was down to 75—reasonably good air quality, by today's standards. By 1989, it was down to 49. (By comparison, in 1970 all of Chicago violated the 75-microgram standard and 69 percent of the city had a count over 100 micrograms; in 1975 only two percent of the city was over 100, and only half was in the 76-100 range.)

This is a difficult subject for environmentalists, particularly American ones, who reap the benefits of a history of cheap, dirty energy, so asking China why it doesn't fix things right away can seem arrogant, as Madrigal points out. But comparing turn-of-the-century Chicago to 21st century Beijing isn't the best standard, either. Not only is the technology better and our understanding of air pollution vastly more advanced, there's historical precedent: the massive cost, of dollars and life, that America saw from pollution in its many years as a developing country, but also its experience in turning around major cities in many fewer years.

Photograph: NASA