One of my pet obsessions, perhaps stemming from my alma mater's rich history of baseball nerds, is the very early history of sabermetrics and computerized analysis. I knew, for instance, that the Oakland A's—before Moneyball star Billy Beane was even drafted, much less their general manager—had adopted the use of computers in the early 1980s, and that braniac Tony LaRussa was an early convert while with the White Sox. Following this thread, I came across this bit of fact from veteran computer journalist Doug Garr:

It's surprising that baseball has taken so long to get around to using computer technology. After all, computers have become a fixture in our everyday lives and baseball is our national pastime. In the late 1960s one old gent did take pains to record the deeds of the Chicago Cubs on IBM punch cards and run them through a computer at the Wrigley factory, but the stats were in no useful form and the method failed to catch on. The game of inches had to wait for more sophisticated and comprehensive software for microcomputer systems.

It's a little off. It was the early 1960s, not the late 1960s. And the "old gent" was one Phil Wrigley, who went through a slightly nuts attempt to modernize his dreadful Cubs with some scientifying:

Although Chicago sportswriters have been quick to condemn the coaching system as another manifestation of Wrigley's eccentricity

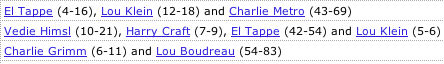

Actually, let's pause here for a second. Wrigley decided that, instead of dumping his latest unsuccessful manager (the Cubs went through six from 1950-1960), he'd just do away with managers altogether for a "a system of rotating coaches." This is why the Cubs' entry on Baseball-Reference.com looks like this for 1960-1962:

Wrigley told the Tribune: "Now, about the word 'manager.' I looked it up and the pure definition is 'dictator….' The job is too much for one man. It's like the presidency. No one man can possibly do all the things required of a manager or the President of the United States."

The Cubs went 60-94 under Grimm and Boudreau. Their rotating cast of coaches went 64-90 and 59-103, respectively. The year after they dumped the system, they improved to 82-80. Anyway, continued:

it actually is an attempt to inject into baseball some of the principles of business management. To Wrigley, for instance, it is ridiculous to call the Cubs a ball club when, in his words, they are really "a corporation organized for profit." Whereas other teams use a statistician to compute averages on individual players, the Cubs use an IBM machine which digests and summarizes all sorts of data, e.g., ground balls, fly balls, right- or left-handed pitcher, weather conditions, etc., on the entire squad. Instead of being disorganized, as some critics have charged, the Cubs are organized to the nth degree. They are organization men in the truest sense of the term; indeed, it would be more accurate to call them the Orgs instead of the Cubs.

[snip]

…the Cubs have five other coaches, each signed to a major league contract as a status symbol, who tour the minor league clubs (called "associated teams" in organization jargon) tutoring specific players the underdeveloped Cubs want to bring up fast. Every coach, with the Cubs or the farm system, is primarily a teacher. Wrigley fears that if the team had a regular manager the youngsters would not be brought along as quickly. A manager, Wrigley says, may be impatient with a youngster because of the pressure to win. A rotating head coach, who knows the job is temporary, is not under this pressure. "If you've got security," Wrigley says, "you can take a much less selfish point of view."

It's not exactly clear what Wrigley, much less his coaches, did with the IBM punch cards. Trib reports suggest the plans were not terribly ambitious: "IBM cards… will be used next season to keep the Cubs' board of coaches up to date on each of their players' average against the opposing pitcher. Wrigley explained that, "for as long as I can remember they have been saying that baseball is a game of percentages. But I've yet to find anyone in baseball who can figure percentages. Go ask Charlie Grimm [three-time Cubs manager and the last one, at that time, to have won a pennant] to figure 2 percent of $1,000."

Wrigley's magic percentage-figuring computer was not embraced by his charges, as was his coaching model predicated on a non-existent concept of the American executive branch. The trail sort of goes cold from there, until it turns up again in Chicago. Back to Garr:

Today, computers are safe at home in the offices and dugouts of the Chicago White Sox and Oakland A's, who pioneered in their use, and of the Toronto Blue Jays, New York Yankees and Mets. The most popular statistics program is The Edge 1.000, which can do everything but spit tobacco juice. The Edge was developed by Dick Cramer, Philadelphia pharmaceutical designer by day, nighttime baseball fanatic and self-proclaimed "sabremetrician" of the Society for American Baseball Research.

The A's were the first team to do statistical analysis with a computer, if you don't count the Cubs, but it appears that they were only used for television broadcasts until the famously old-school Billy Martin was replaced by Steve Boros in 1983. If so, it's likely that the first major change a baseball team made due to computer analysis was by the White Sox, starting in 1982. They'd hired a 22-year-old north-side native, Dan Evans, a Lane Tech grad lifelong stats nerd who'd interned with the Sox as a college student at DePaul, to run Cramer's system. Paired with the analytical duo of Tony La Russa and Dave Duncan, the team began to apply Evans's research to the field, Alan Schwartz writes: "When the printouts showed that Rudy Law, a left-handed hitter, actually performed better against lefthanded pitchers, La Russa eased off pinch hitting for him in those situations."

Lefties who hit lefties better is a rare phenomenon, but shouldn't require a computer to notice. It gets more entertaining, though, as La Russa used early fielding metrics in the service of micromanaged contrarianism: "The data on where grounders went through the infield suggested that putting Mike Squires at third base—despite being left-handed, which is verboten for the hot corner—would not be too costly, and Chicago played him there under certain conditions." Those certain conditions were limited: one game in 1983 and 13 in 1984, only four of which were starts and only one of which he completed at third. Squires did make putouts on all five chances he got at third, though.

The biggest change, though, was to the field itself. Evans noticed the Sox were hitting a ton of fly balls that died on the warning track. So the White Sox moved home plate forward the year after Evans arrived. In 1982, they'd hit 51 home runs in Comiskey; in 1983, they hit 84 home runs. In 1984, they hit 103. (Of course, they also gave up more home runs at home: 43, 64, and 77 in those same years.) Evans, of course, went on to become the White Sox's [update: assistant] GM and later the Dodgers' GM, where he hired former Sox intern and arbitration specialist Kim Ng. To complete the sabermetric circle, Evans is now a columnist for Baseball Prospectus.

Related: The Cubs just hired Tom Tango (not his real name), inventor of FIP and wOBA.

NB: I'm following NYT style on the possessive form of "White Sox," in case you were wondering.

Photograph: Monika Thorpe (CC by 2.0)