Just before the year ended, an Englewood kid's letter to the President made national news. Through a roundabout chain, Malik Bryant's sole wish—for safety—made it into the hands of Barack Obama. It also touched off a discussion with some Chicago journalists I follow on Twitter about the seemingly intractable nature of violence in the city and Obama's perceived lack of interest in it.

This happens, periodically, and the dialogue ends on a depressing note. As last year ended, homicides were down but shootings up 14 percent.

But not all of the numbers or stories that came out of last year were hopeless. Here are a few sprouts of good news that emerged in 2014.

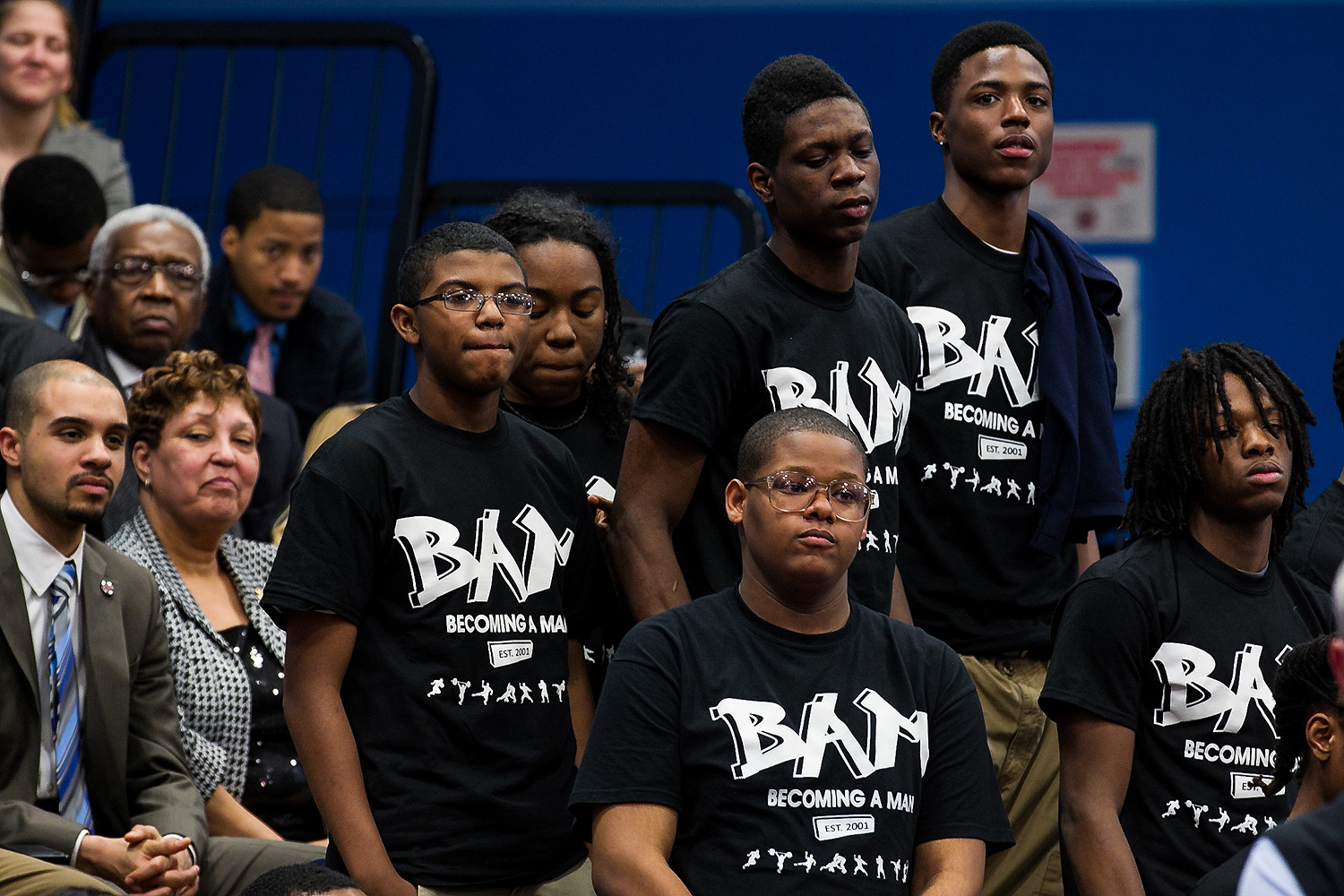

1. Becoming a Man gets a boost from the feds

Almost six years ago, the University of Chicago's Crime Lab launched a massive initiative to identify a program to reduce violence by addressing one of its root causes—a lack of emotional and social regulation that leads to impulsive violence. Among thirty proposals, the Lab settled on Becoming a Man—Sports Edition, and rolled out a randomized experiment in 2010. On one hand, it was an intense study, rare in its field, with some 2,500 subjects. On the other, it was not a particularly intensive or expensive program—"light-touch intervention," in Lab director Jens Ludwig's words. But it caused violent-crime arrests to drop 44 percent.

In July of this year, BAM got $10 million from the federal government to continue its work. Some of that was earmarked for the associated Match program, a more intensive, academics-focused tutoring program that also saw promising results in a study released at the beginning of the year. The BAM program, and the research that went into its development and evaluation, has also influenced the President's "My Brother's Keeper" initiative, which hit $200 million in funding earlier this year.

2. One Summer Plus follows in BAM's footsteps

The next big news from the Crime Lab came this year, from a summer-mentoring program that paid Chicago teens minimum wage to work summer jobs with the help of a mentor. The principle is similar to BAM—the kinds of skills learned in a workplace translate to the kind of social-cognitive learning that BAM is designed around. And the results were remarkably similar.

3. PTSD becomes part of the language of violence

Generally associated with wartime trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder is being taken more seriously as a problem in violence-torn neighborhoods. Cook County Jail in particular is screening for the disorder as part of its intake, as Frank Main reported on the last day of 2014.

Not all the news about PTSD has been good. Late last year, Steve Bogira published a long piece on Safe Start, a therapeutic program for families with children at risk for PTSD or similar problems after exposure to violence. As Bogira found, it seems to work very well, but it also doesn't receive much money—a risk that programs like it run after an initial wave of interest, and something to be aware of for the future of Becoming a Man and One Summer Plus.

But it's being written about—by Main, by Bogira, by ProPublica's Lois Beckett, by the Trib's Annie Sweeney—more than I've been accustomed to in the past. Like social-cognitive learning, thanks to the efforts of people like James Heckman and Paul Tough, it's getting an airing as part of the civic toolkit in preventing future violence.

4. We're getting a better sense of the scope of the problem

Chicago native Andrew Papachristos, a Loyola- and U. of C-trained sociologist now at Yale, has continued to study Chicago violence as a social network, and the results are fascinating. And not necessarily discouraging—Papachristos, using arrest records, identified small networks of Chicagoans who are at a very high risk of being shot or murdered. And from the CPD's year-end wrap-up, it appears they're trying new tactics based on such insights:

The department has continued to test innovative strategies like "two degrees of association," which identified more than 400 people in the city most at risk of being involved in violence either as the perpetrator or victim. Top police officials and community leaders tried reaching out to those on the list, warning them they were going to be watched more closely by police, but also offering them social services.

Will it work? Not necessarily; not all interventions, even those based on good ideas, work in the end. But that's how you find out what does, and why.