Once upon a time, Americans dreamed big. As they watched the suburbs expand, pulsing with economic activity, they set in motion ambitious plans based on new technology to reduce the congestion building along the veins of suburbia.

That time was the '90s. That place was, um, Rosemont. And Rosemont would see that dream built—only it was built in Massachusetts in a form too clunky and expensive to survive.

While looking up something or another, I came across a 1991 "Proposal for a Personal Rapid Transit Demonstration System" from the Village of Rosemont. Envision, if you will, a network of autonomous, futuristic five-person pods zipping through the glassy canyon of corporate headquarters near O'Hare, alighting at their passengers' chosen destination. It would have looked like this.

Were you sent here by the devil? / No, good sir, I'm on the level.

It was, indeed, a serious proposal, one of many submitted to the Regional Transportation Authority from Rosemont, Schaumburg, Deerfield, Lisle, Addison, and Naperville. When the RTA announced its plans in 1990, the Tribune's transportation writer, Gary Washburn, described the authority's long-term ambitions and the need it was meant to fill:

If the test proves successful, they believe the system could be expanded throughout the metropolitan area, running down expressway median strips, on abandoned rail lines that connect suburbs with one another and within towns such as Oak Brook and Schaumburg that have experienced dramatic commercial and residential development.

Chicago's suburbs had about 20 of every 100 jobs in the region in 1950. Today the total is almost 60 percent, and experts believe that the figure will rise to 65 percent by 2010.

Moreover, more than half of all Chicago area workers now commute from one suburb to another, while those making the "traditional" trip from suburb to Chicago total fewer than 15 percent.

Decades later, Chicago still lags behind in this area. As Steven Vance wrote last year:

Paris, a similarly-sized metropolis, has much better suburb-to-suburb rail and bus connections, which run at high frequencies all day and during weekends. MPC notes that New York City and Toronto are “quickly developing round-the-clock frequent services on their commuter rail lines.” Chicagoland has actually regressed: A map in the report shows that in 1950, frequent service reached further into Chicagoland from downtown than in 2010. And while 82.2 percent of Chicagoland jobs are in reach of transit, “most of that access is provided by slow and infrequent bus service,” MPC writes.

It wasn't the only avant-garde transportation idea that the RTA was considering at the time "in an effort to coax drivers, particularly in the suburbs, out of their cars." In June of 1992, as the competition to get PRT continued, the agency was also investigating SERCs, or "stackable electric rental cars," approximately the size of a Honda Accord, with a range of 28 miles and a top speed of 50-60 miles an hour. The system would allow workers to take the Metra to a SERC station, drive the last few miles to the office or home, and return it by the next day—sort of like bike-share for tiny electric cars. It doesn't seem to have gone beyond a symposium on the technology.

But the PRT plan got serious. Rosemont retained Winston & Strawn—around the same time the RTA hired them for lobbying work—at a cost of $50,000. They spent another $50,000 to prepare for the application. The mayor told the Tribune in May of 1991 that they were prepared to spend another $100,000 to get the RTA experiment. And Rosemont got the nod, though it took two years.

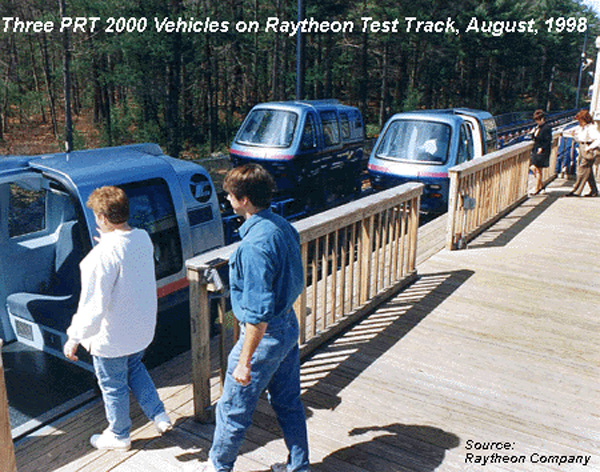

In 1998, eight years after and $22.5 million dollars after the RTA set it in motion, Rosemont's PRT system came to life. It came to life on a test track at Raytheon in Massachusetts, but nonetheless, it existed, in RTA-emblazoned glory. RTA officials were pleased. This is what it looked like.

They weren't the sexy, low-slung bullets of the proposal, but they were endearing in their own way.

The $270,000 prototype cars traveled at 30 miles per hour, carrying four people, who had to wait no more than three minutes to board, and the cars stopped only to let others merge from the station onto the main track. In and of itself, it was a significant technological achievement:

Headway is limited by the switch maneuvers – the handling of cars moving toward converge points at the same time, slowing one to give priority to the other. PRT with its many stations, all off-line, and its looped-grid layout of one way track is probably the most switch-intensive transport system yet conceived. The system has to handle repeated close encounters at switches requiring enormous reliability in sensing, computing, braking, and other controls, PRT experts say.

It worked as planned, though the estimated cost had grown from $40 million to $124 million, $70 million of which would have to come from RTA, on top of the $22.5 million that had been spent to that point. It wasn't just the usual cost overruns; as the project grew, so did the cars and the track. "Raytheon officials said the 4-person cars were necessary to meet wheelchair carrying requirements and that the longer and wider wheelbase was needed to provide a smooth comfortable ride and meet safety standards," Peter Samuel wrote in a 1999 piece for ITS International titled "Raytheon PRT Prospects Dim but not Doomed."

"The wrong people were selected to build it," says Jerry Schneider, a professor emeritus in civil engineering at the University of Washington who maintains a thorough website focused on the history and technology of PRT and other surface-transportation alternatives. "It cost more to build [than it was worth to RTA]," Schneider says.

At the project's inception, it was intended to cost $10-$15 million per mile. $124 million for 3.5 miles put it in the realm of light rail, defeating much of the purpose of PRT.

The cost overruns alone might not have been enough to derail the Rosemont PRT. But Raytheon hit hard times, and in 1999, dumped its PRT business. When the plug got pulled in 2000, the Tribune reported that "the project was near death last October, when Raytheon's financial losses prompted it to abandon the transit business."

The PRT dream isn't dead; "dim but not doomed" is still an apt decription. Morgantown, West Virginia runs self-propelled cars between downtown and the University of West Virginia, though the 20-person cars are much larger than the PRT dream of individual autonomy, and during peak hours the system runs point-to-point instead of on demand—like an airport people mover with some flexibility built in.

As Eric Jaffe writes, PRT ideas are continually circulating, but they're hard to envision in our driverless-car future. Or, in the meantime, the era of Uber, in which the eternal dreams of transit engineers are built around the car rather than replacing it.