A while back I wrote about a mapping project based out of the University of Richmond that documented how sweeping the practice of redlining was in Chicago in the early 20th century. Now they're back with another, equally compelling map: Renewing Inequality, which shows how federally funded urban renewal projects (attempts to redevelop or clear blighted inner-city areas) from 1950 to 1966 displaced about 300,000 families nationwide. At the average family size of 1950, 3.54 people, that's just over one million people displaced by a federal program, a population larger than Baltimore was in 1950.

Only New York City displaced more families than Chicago, but it displaced far fewer people relative to its population. (Below, "displaced" refers to total displaced individuals, based on an estimate of 3.54 people per family.)

.jpg)

About one-third of displacements in Chicago came from two urban renewal projects: Hyde Park-Kenwood, which displaced about 4,000 families, and Lake Meadows, which displaced another 3,400 families.

The two are related. Lake Meadows was "urban renewal," but it wasn't "slum clearance," exactly. As Wendell Pritchett writes, it wiped out a lot of middle-class property:

In 1947, pushed by this coalition [business leaders and nonprofits, including IIT and the University of Chicago], Chicago Mayor Martin Kennelly reached an agreement with New York Life Insurance Company to build the "Lake Meadows" development on the near Southside. While much of the proposed clearance area was deteriorated, New York Life created a controversy when it demanded that several well-maintained blocks be cleared because they would afford better views of the lake. Even redevelopment advocates acknowledged that the plan ignored "actual slum areas completely" and planned "the demolition of a well-kept Negro area where the bulk of property is resident owned, its taxes paid, and its maintenance above par."

The development, you may not be surprised to hear, "replaced only a small percentage of the units that were demolished and exacerbated the severe housing shortage in the city."

Where did the displaced residents go? Forced out of the near South Side, they went further south—to Hyde Park and Kenwood. Which then, mostly in the form of the university, decided it needed urban renewal too, in large part because of the flood of new residents created by the Lake Meadows project.

To find funds, they went straight to the top—the White House—inaugurating a new era in the transformation of American cities. As LaDale Winling, whom I interviewed for the redlining piece, writes in Building the Ivory Tower, Inland Steel executive Clarence Randall needed only eight days to secure a meeting with President Dwight Eisenhower about federal slum-clearance funds for Hyde Park.

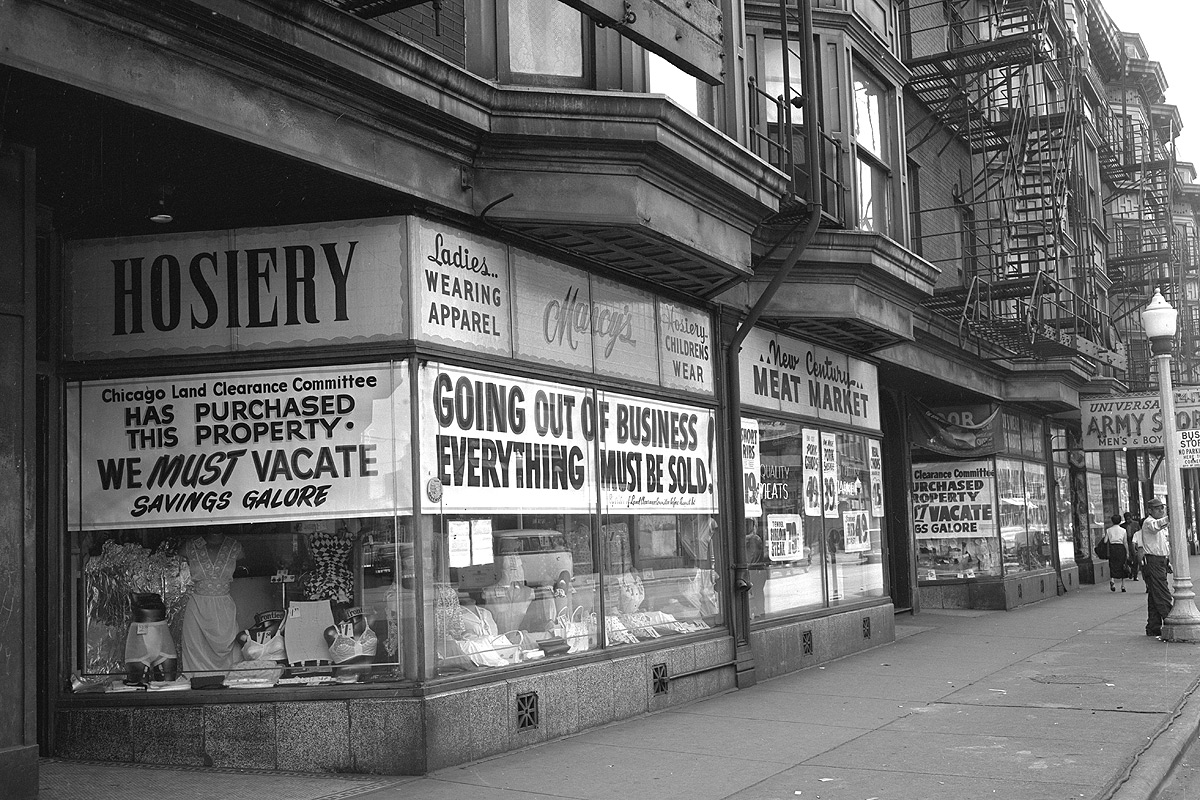

The project they gladhanded Eisenhower about was Hyde Park A & B, which went down as an in/famous remaking of an urban space based around the architecture of Harry Weese and I.M. Pei. What had been a mixed-use commercial and entertainment district in the heart of the neighborhood became a modernist residential area. The structures are still in demand, but the center of the neighborhood remains largely denuded of commercial life, and since Jane Jacobs's The Death and Life of Great American Cities it's been used by many as a study in how not to remake a community.

The effect of urban renewal on Hyde Park's business community was so profound that Harper Court, a small shopping area, was constructed to preserve some foundation for the neighborhood's small businesses. But coming over a decade after Hyde Park A & B, only three of the displaced businesses could take advantage of it. Almost 50 years later, Harper Court itself got plowed under, so that the university could turn "a blighted retail district" into "a thriving commercial area."