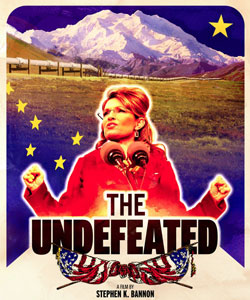

Roger Ebert watched the new Sarah Palin documentary The Undefeated, at a reasonably well-attended screening of 180 at the Gene Siskel Film Center, and caught something interesting:

Roger Ebert watched the new Sarah Palin documentary The Undefeated, at a reasonably well-attended screening of 180 at the Gene Siskel Film Center, and caught something interesting:

What astonished me is that the primary targets in the film are conservative Republicans. Yes, there are the usual vague references to liberals and elitists (although I heard the word "Democrat" only twice). But the film’s favorite bad guys seem to be in the GOP establishment. This seems odd, considering that the target audience is presumably Republicans.

In the context of the debt ceiling debate, however, it really shouldn’t be astonishing, because a similar dynamic is playing itself among the House majority. It was reported that, after last night’s dueling speeches by President Obama and House Speaker John Boehner, the latter was overheard muttering "I didn’t sign up for going mano-a-mano with the President of the United States" ("his remark was dry in tone").

No one seems to have caught any context, if there was any, but one interpretation is that Boehner has been forced into a battle he doesn’t necessarily want by his conservative colleagues:

But recklessness does equal power: that’s why Eric Cantor, the House Majority Leader, and John Boehner, the Speaker of the House, have implied that they’re willing to go over the cliff (in part by suggesting that their fellow party members will force them to) but also that they can be persuaded to do the right thing.

Take the plan proposed by Majority Leader Mitch McConnell: despite its silly fine print forcing a "disapproval" vote on raising the debt ceiling, it basically would have allowed business as usual.

And it was DOA, thanks in part to the much, much harder line pushed by freshman Illinois rep Joe Walsh (who was MSNBC’s go-to House Republican last night after the festivities).

The House is basically pulling the GOP to the right. What will be interesting to see is if the same process takes place during the 2012 primaries—and that’s why The Undefeated is less concerned with Democrats than Republicans. And it’s not necessarily a futile shift in the long run, even if it looks like it’s pulling the GOP apart in the short run. Choosing Barry Goldwater over more easy-to-swallow moderates like Nelson Rockefeller led to the GOP getting pounded in the 1964 presidential election, but he left an indelible mark on the party, and the nation’s politics as a whole.

For all the sweating about the progressive left, I think Democrats, for better or worse, tend to actually suffer from less internecine warfare. Certainly the progressive left tends to think they have less influence on the direction of the Democratic party than their counterparts. But Nicholas Beaudrot makes an interesting point:

On the contrary, liberals had an enormous effect on the policy debate during the Democratic Presidential Primary. The health care plans of John Edwards in 2008, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton were all dramatically to the left of the proposals from John Edwards in 2004, John Kerry, and Howard Dean, none of whom attempted to guarantee health care coverage to all Americans. Likewise, all major candidates signed on to some form of cap-and-trade legislation, something that didn’t happen during the previous primaries. The Professional LeftTM ought to be proud of its accomplishments during the most recent Presidential cycle.

If you buy that, that means the wings of each party have stretched out the spectrum of popular ideology over the past few electoral cycles, and the result is like balancing a pole that’s gotten longer: the center may be in about the same place as it was back in the ’90s, but overall things are heavier and more unwieldy. This has led to DC types begging for a centrist third party to cure us of our ills. Which is odd, since it’s that centrism that’s being systematically rejected right now—unless, of course, intraparty divisions make it impossible to do basic housekeeping. We’ve got a week to find out.

Update: Here’s a nice quick rundown of third parties throughout American political history.

Update II: Yuval Levin of the National Review thinks the Republicans have won considerable ground over the debt-ceiling debate, and I think he’s got a point, especially given that at this point it’s not that different from Harry Reid’s proposal:

As the details of the Boehner bill become clearer, it’s increasingly apparent that the bill is just what the moment calls for: significant cuts achieved through statutory sequestration caps, no tax increase, no backsliding on entitlement reform or implicit acceptance of Obamacare, a path to another process that could lead to more cuts without tax increases, and the setting of a precedent that from now on increases in the debt ceiling must be accompanied by proportional spending cuts. It’s far from perfect, of course—meaningful entitlement reform is the only way to really address the debt problem, and even short of that some more significant discretionary cuts would be good—but Republicans don’t control Washington, and given their limited formal power, an end to this process that looks something like this bill would be pretty remarkable.

Yet it’s not viewed that way by some members of Boehner’s House colleagues. The question is: how many? Even if the Boehner bill represents minimal losses, are they willing to cut even those and lift the ceiling?

Update III: Turns out the question to "how many" is "a lot."