Here’s an interesting little example of the choose-your-own-adventure nature of statistical interpretation.

This weekend the Chicago Tribune editorial board published an editorial blaming high teenage unemployment on the 2007 adjustment to the minimum wage from $5.15 to $7.25:

For the vast majority of adults, who earn well above the federal floor, the change was irrelevant. The greater impact was among adolescents. About a quarter of those working make no more than the minimum.

So it was not entirely surprising to see the unemployment rate of those 16 to 19 years old went from 14.8 in early 2007 to 27.1 percent in October 2009 — shortly after the final stage of the raise took effect. Today, it’s 24.2 percent.

It came a couple days after the Wall Street Journal published an an editorial making a similar argument:

Back on planet Earth, the minimum wage increase has coincided with the plunge in the percentage of working teens. Before the most recent wage hikes, roughly seven million teens were working. Now there are closer to five million with a job and paycheck.

Black teens have had the worst of it, with their unemployment rate rising to 41.6% in April from 29% in 2007, faster than almost any other group. A 2010 study by economists William Even of Miami University of Ohio and David Macpherson of Trinity University found that as a result of the $2.10 increase in minimum wage, "teen employment dropped by 6.9 percent. . . . For the teen population with less than 12 years of education completed, teen employment dropped by 12.4 percent." For teens priced out of the labor market, their wage fell to zero.

In September of 2010, according to BLS statistics, black teen unemployment peaked at 49.7 percent, meaning that, nationwide, it was about twice as high as the rates that shocked Ebony in the 1960s. It’s not a historical high—that would be 1982 and 1983, when it twice peaked at 52 percent—but it’s very, very close. White teen unemployment hit a post-1954 historic peak during the downturn, at 24.2 percent in May 2010. Unsurprisingly, the previous peaks also came during 1982 and 1983 (same link as above).

This should be of concern. As William Julius Wilson told the London School of Economics in 1998 (PDF):

The consequences of high neighbourhood joblessness are more devastating than those of high neighbourhood poverty. A neighbourhood in which people are poor, but employed, is much different from a neighbourhood in which people are poor and jobless. In When Work Disappears (1996) I attempt to show that many of today’s problems in America’s inner-city ghetto neighbourhoods — crime, family dissolution, welfare, low levels of social organisation and so on — are in major measures related to the disappearance of work.

It’s not all to do with unemployment; Wilson argued that joblessness and stagnant wages both contribute to crime, and a 2002 study by Eric Gould, Bruce Weinberg, and David Mustard in The Review of Economics and Statistics (PDF) argued that a review of the literature finds "moderate, but often inconclusive evidence that unemployment rates are positively associated with crime" while finding a greater correlation between wages and crime.

But I’m getting off on a tangent. What about the minimum wage and teen unemployment?

Invictus, of the essential econ blog The Big Picture, took apart an identical argument in 2009, showing that if you go back through several minimum-wage hikes, teen unemployment doesn’t correlate with them; instead, it correlates with recessionary economic conditions.

Now take a look at the Tribune‘s statement again:

So it was not entirely surprising to see the unemployment rate of those 16 to 19 years old went from 14.8 in early 2007 to 27.1 percent in October 2009 — shortly after the final stage of the raise took effect. Today, it’s 24.2 percent.

But you could also say the same thing about almost any demographic. The unemployment rate of those 25 and older went from 4.5 percent in April 2007 to 10.8 percent in October 2009; for those in that demographic with a college degree, it went from 1.8 percent in March 2007 to 4.8 percent. The teen unemployment rate grew more, but not proportionally more.

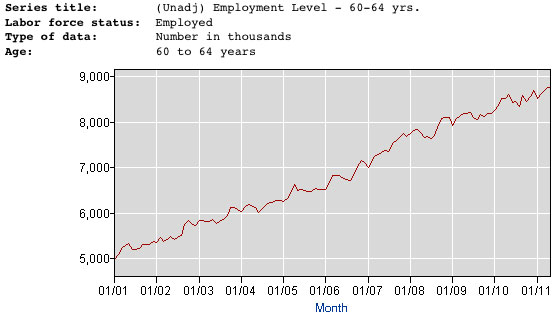

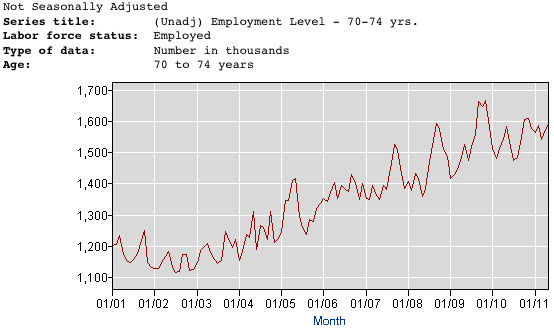

Invictus, seeing the argument repeated again in the WSJ, came back to tell us all again, this time comparing teen employment with employment in the 55+ demographic. And the numbers are pretty striking: the change in the teen employment to population ratio over the past decade is the exact opposite of the 55+ ratio.

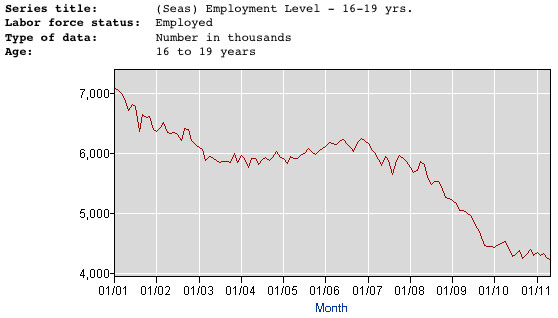

In short, while fewer teens are working, more old people are working. Compare just the raw numbers of employed 16-19 year-olds…

…to that of different old-person demographics…

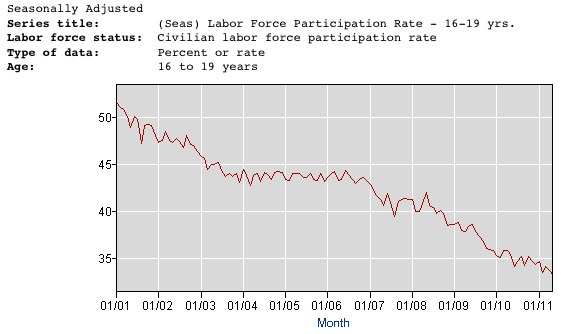

Though the drop is steeper from 2007 onwards, the total number of employed teens has been dropping since 2001. Viewed as a function of the civilian labor force participation rate, the decline is more gradual:

That obviously doesn’t account exclusively for minimum-wage workers, but there’s evidence that the aging of the employed population has pushed teens out of minimum-wage jobs:

* In 2002, there were 605,000 teens making at or below the minimum wage. In 2010, there were 994,000. As a percentage of minimum-wage workers, teens decreased from 27.9 percent to 22.8 percent.

* In 2002, there were 167,000 people ages 45-54 making at or below the minimum wage. In 2010, there were 450,000. As a percentage of minimum-wage workers, this age contingent increased from 7.7 percent to 10.5 percent.

The Wall Street Journal cites a 2010 study out of the Employment Policy Institute—which, institutionally, tends to favor expansion of the earned income tax credit over minimum-wage increases—which estimates that the 2007-2009 minimum-wage increase put 114,000 teens out of work. Which, if true, would obviously not be insignificant, but would still account for less than 10 percent of the decline in total number of employed teens since 2007 (much less since 2001, which seems to be the source of the "seven million teens" cited in the editorial).

And there are other demographic changes to consider. For instance, the WSJ editorial cites a report by the Chicago Fed:

As a 2006 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago put it: "The drop in teen labor force participation may also have implications for future productivity growth. In general, labor market experience tends to raise subsequent earnings."

It’s worth noting that the editorial, which attempts to blame post-2007 minimum-wage hikes for teen unemployment, cites a 2006 study addressing the phenomenon as a long-term trend. What did the Chicago Fed conclude back then?

It seems likely that the most important factor behind the long-term decline in teen labor force participation is the significant increase in the returns to education that began shortly before teen participation peaked. The wage premium associated with a college education is now nearly twice as high as in the late 1970s, and teens appear to have responded to this development by spending more time in school. Indeed, school enrollments have increased by roughly 25% since 1985, with much of the recent increase the result of a major increase in summer school enrollments.

Teens in school are much less likely to participate in the labor force. Indeed, the simple shift in the share of teens enrolled in school can account for about two-thirds of the decline in participation through the mid-1990s. An additional portion of the decline is attributable to lower rates of participation among those enrolled in school, which, to some extent, may be due to an increase in the intensity with which enrollees pursue their studies. Relatively little of the decline is attributable to lower rates of participation by those who are not enrolled in school.

In keeping with that theme, college enrollment in the U.S. is at record highs, reflecting generally higher school enrollment trends among Americans ages 16-24:

The enrollment rates for 7- to 13-year-olds and 14- to 15-year-olds were generally higher than the rate for 16- to 17-year-olds, but the rate for 16- to 17-year-olds did increase from 90 percent in 1970 to 95 percent in 2009. As of August 2010, the maximum compulsory age of attendance was 18 years in 20 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.), 17 years in 11 states, and 16 years in 19 states.

Young adults ages 18–19 are typically transitioning into college education or the workforce. Between 1970 and 2009, the overall enrollment rate for young adults ages 18–19 increased from 48 to 69 percent (see table A-1-1). During this period, the enrollment rate for 18- to 19-year-olds at the secondary level increased from 10 to 19 percent, while at the college level the rate rose from 37 to 50 percent. Between 2000 and 2009, the college enrollment rate increased from 45 to 50 percent.

None of which is to deny the possibility that minimum-wage hikes contributed to the considerable jump in teen unemployment from 2007-2009. But the research on that varies quite a bit, and for the most part comes before the recent economic crisis and minimum-wage adjustment came simultaneously. While the Employment Policy Institute study above argues that the 2007-2009 minimum-wage hike increased teen unemployment, the most recent study I could find, an April 2011 paper in Industrial Relations which attempts to correct for local economic variations ("Do Minimum Wages Really Reduce Teen Employment? Accounting for Heterogeneity and Selectivity in State Panel Data," PDF) found: "Put simply, our findings indicate that minimum wage increases—in the range that have been implemented in the United States—do not reduce employment among teens."

Meanwhile, there are many other strong factors conspiring against teen employment: some bad (widespread unemployment, increasing health-care costs, the effect of the economic crisis on employment savings), some neutral (the baby boom), some arguably good* (increased high school and college enrollment). Opening up the consideration of sources beyond one study greatly complicates the picture, but also makes it arguably less discouraging.

Related: Megan Cottrell on SB 1565, an ambitious state minimum-wage bill that’s currently stalled in committee.

* Obviously I value education, but if high unemployment is forcing people into college that would not otherwise go, that may or may not be good.