The shootings in Aurora, and to a certain extent the rise in homicides in Chicago this year, have brought gun control to the forefront for the first time in awhile. Both Obama and Romney addressed it this week, as one might expect. Romney's response was brusque: "And so we can sometimes hope that just changing the law will make all bad things go away. It won't. Changing the heart of the American people may well be what's essential, to improve the lots of the American people."

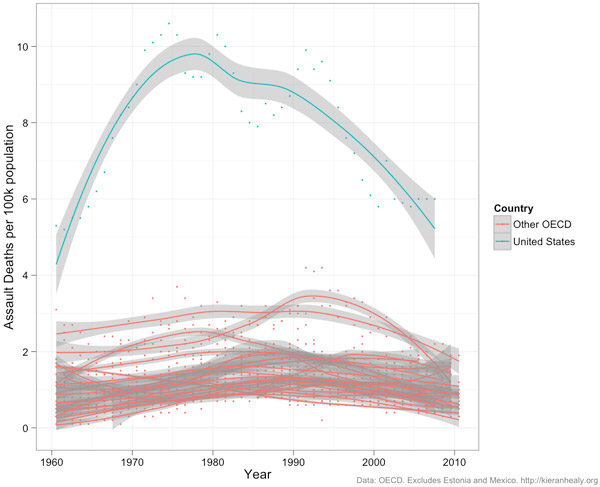

But in some small way it does contain a point. America is a very violent country. Duke sociologist Kieran Healy (via Ezra Klein) produced a chart comparing the U.S. to OECD countries (besides Mexico and Estonia) in terms of deaths from all forms of assault:

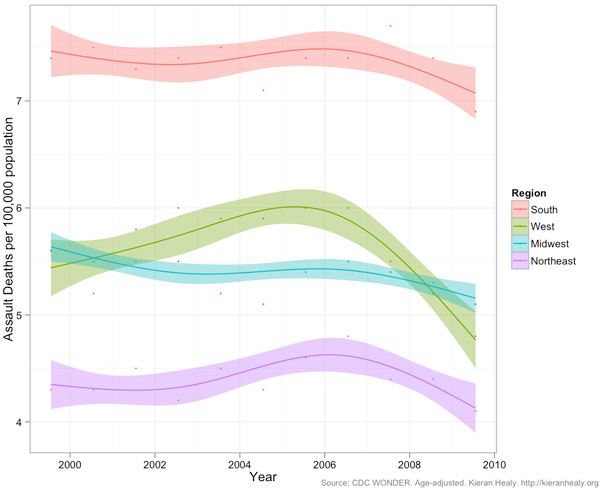

The U.S. is simply much more violent than other developed countries. And the region that brings up the national average is the South:

It's not exclusively Southern states with high assault-death rates; a third chart by Healy shows that some Western and Midwestern states have higher rates than some Southern states. But by region, the difference is dramatic.

This has been the case for many, many years, and many causes have been proposed: hot weather, economic disparity, the legacy of slavery and the Civil War. In 1996, four psychologists from Midwestern universities, led by UIUC's Dov Cohen and Michigan's Richard Nisbett, designed a lab experiment to test if Southerners were more prone to violence, and in particular violence stemming from a "culture of honor" endemic to the region. They ran their subjects through a battery of tests designed to provoke: bumping the subject in a hallway, calling him an "asshole," forcing a game of "chicken" in a hallway (anecdatally, I am more likely to bump rude people on the bus or sidewalk than my friends, and am also Southern), and other subtle manhood challenges. The researchers then took qualitative and quantitative data (emphasis mine):

The findings of the present experiments are consistent with survey and archival data showing that the South possesses a version of the culture of honor. Southerners and northerners who were not insulted were indistinguishable on most measures, with the exception that control southerners appeared somewhat more polite and deferential on behavioral measures than did control northerners. However, insult dramatically changed this picture. After the affront, southern participants differed from northern participants in several important cognitive, emotional, physiological, and behavioral respects.

The quantitative data was fascinating as well:

We averaged the two postbump measurements and then computed a change score: (average postbump cortisol level – prebump cortisol level) ÷ (prebump cortisol level). As may be seen in Figure 1, cortisol levels rose 79% for insulted southerners and 42% for control southerners. They rose 33% for insulted northerners and 39% for control northerners. We had predicted that insulted southerners would show large increases in cortisol levels, whereas control southerners and both insulted and control northerners would show smaller changes.

[snip]

As with cortisol, we averaged the two postbump measurements and then computed a change score: (average postbump testosterone level – prebump testosterone level) ÷ (prebump testosterone level). As may be seen in Figure 2, testosterone levels rose 12% for insulted southerners and 4% for control southerners. They rose 6% for insulted northerners and 4% for control northerners.

After provocation, Southerners were not only more angry on the outside, they were more angry on the inside, down to their neurochemistry. (The authors also theorize that Southern politeness could be a response to Southern aggression—if Southerners are more likely to take offense than other regional cultures, it follows they would be less likely to give offense, for safety's sake.)

Cohen and Nisbett's psychological study was, in part, a response to several classic works of history about Southern (and other American) folkways, including David Hackett Fischer's Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, and Bertram Wyatt-Brown's Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South. Both books share similar themes, beginning with the idea that Southern ideas of justice and honor were imported from the lawless British borderlands, creating an "exceptionally violent world," in Hackett Fischer's words. "Backcountry proverbs did not glorify fighting for its own sake, but fighting for the sake of winning. Here was an ethic of violence which had been formed in ambuscades and border-raiding. It had nothing to do with combats of chivalrly or the idea of war as a gentleman's game."

As Hackett Fischer notes, blood feuds and retributive justice were common in the British borderlands, and were imported into American culture, everywhere from the lands of the Hatfields and McCoys to Williamson County, Illinois (as described in Paul Angle's brilliant Bloody Williamson, an account of the violence in that downstate, very Southern county). Southern law also treated property crime differently from violent crime:

Backcountry courts tended to punish property crimes with the utmost severity, but to be very lenient with crimes of personal violence. In Cumberland County, Virginia, during the eighteenth century, a court administered the following punishments: for hog stealing, death by hanging; for scolding, five shilling fine; for the rape of an eleven-year-old girl, one shilling fine. This structure of values continued for many generations in the backcountry. Historian Edward Ayers finds that in the southern upcountry during the nineteenth century, county courts "treated property offenders much more harshly than those accused of violence."

Life was cheap; property was expensive.

Those wronged by crime, in the absence of legal retribution, were expected to enact revenge themselves. Hackett Fischer cites Andrew Jackson's mother as an example of "backcountry attitudes towards order": "never tell a lie, nor take what is not your own, nor sue anybody for slander, assault, and battery. Always settle them cases yourself." He calls this lex talonis, the rule of retaliation. In some instances, honor overrode law; Wyatt-Brown mentions a case in Kentucky in which an adolescent shot and killed a teacher for whipping his brother; his counsel pled that "he had acted to avenge family honor," and the boy was acquitted.

Youth, for Southern boys, was also violent. Another north British tradition was violent, warlike games: "Scots and English" was an early version of "Capture the Flag," in which two teams of boys piled their hats and coats, lined up, and went on "raids" across the lines; competitors lost if they were knocked down or tackled (we played touch capture the flag, but it was still the game most likely to get someone hurt). As they got older, "Scots and English" became "rough and tumble," essentially just a violent street fight that often ended with noses bitten off or eyes gouged out. Hackett Fisher quotes an English prisoner as writing that "An English boxing match… is humanity itself compared with the Virginian mode of fighting… biting, gouging, and (if I may so term it) Abelarding each other."

What does this have to do with Chicago, and violence in Chicago? In 1986, Nicholas Lemann wrote a lengthy, two-part series for The Atlantic on crime and poverty in Chicago. One of the things he encountered was just how Southern Chicago is:

Although the migration ended in the early seventies — again, because jobs had become scarce in Chicago — there is still considerable movement back and forth, and the South is very much in the minds of black Chicagoans. Most of the very successful local blacks who are held up as role models are southern-born: Jesse Jackson (South Carolina), John H. Johnson, the owner of Ebony (Arkansas), Oprah Winfrey, the TV host who appeared in The Color Purple (Mississippi), Walter Payton, of the Chicago Bears (Mississippi), the Reverend Johnnie Colemon, the pastor of the biggest church in Chicago (Mississippi).

[snip]

Black Mississippians go to Chicago too. Recently, at a student assembly of a black Catholic grade school in Canton [Mississippi], I asked the children how many had been to Chicago, and nearly every hand went up. Often they went for long visits with relatives in the summers. (How many want to live in Chicago when they grow up? I asked. No hands. Why not? An immediate chorus: "Too dangerous.") At one of Chicago's worst high schools — Orr, on the West Side — I asked a class how many were born in Chicago. Almost everyone was. But almost everyone's mother had been born in Mississippi. Many of the mothers of a class of eighth graders at Beethoven School, an elementary school whose students all live in the Robert Taylor Homes, were from Mississippi.

Part of Lemann's thesis, not that he ignores the effects of segregation and concentrated poverty, is that the divide between city and backcountry was also brought north: "Every aspect of the underclass culture in the ghettos is directly traceable to roots in the South — and not the South of slavery but the South of a generation ago. In fact, there seems to be a strong correlation between underclass status in the North and a family background in the nascent underclass of the sharecropper South." Lemann also found the opposite—a correlation between middle-class status in the nascent middle-class of urban Canton and mobility in the North.

Lemann spoke to a white farmer in Canton whose land was worked by sharecroppers, and the similarities between sharecropping and the other peculiar institution are impossible to miss: "See, I'd pay 'em on the basis of — I'd go and ask him how many kids he had out in the field. Because they had to hoe. I'd let them have about twenty up to sixty dollars a month. But they'd always want more money…. They'd go out in the field when they were ten or twelve, as soon as they were big enough to pull a hoe. If they wouldn't put the kids in the field, why, then we'd whup 'em. Then they wouldn't give us any more trouble. We'd tie 'em up and whup 'em with a plow line." The farmer, in his eighties, still had one sharecropper working for him, a 66-year-old with lung disease: "I worked him from goddamn sunup to sunset and then at four in the morning I'd get him up again."

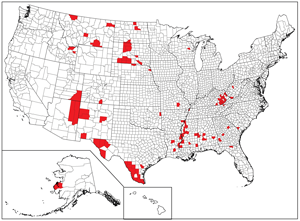

Sharecroppers were tied to the land, and landlords, by a peonage system similar to the truck system of the Appalachian coal mines, made famous by Tennessee Ernie Ford's "Sixteen Tons." Of the 100 counties with the lowest per-capita income as of 2000, there's a high concentration in the sharecropping region surrounding the Mississippi, and in coal country:

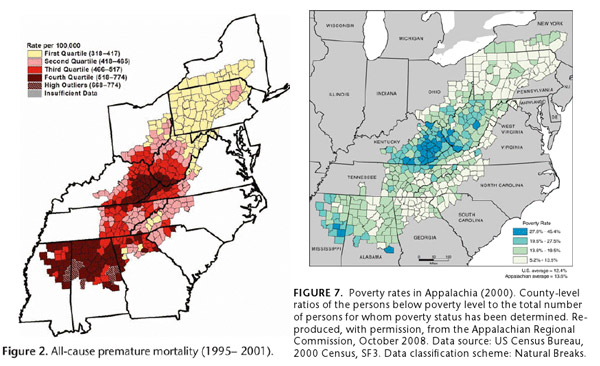

Eastern Kentucky in particular has some of the highest concentrations of extreme poverty in America. Drug abuse is epidemic in eastern Kentucky; long before the abuse of prescription drugs became a national crisis—currently the "nation's biggest drug problem," accounting for more overdoses than all illicit drugs combined—it was a regional one spanning Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia. Also epidemic in the region: black lung disease, again. Across the board, poverty and mortality are high in central Appalachia, and especially in Eastern Kentucky:

Appalachian migrants, as well, also faced intense discrimination, and responded with intense isolation, after coming north as part of a smaller Great Migration.

The theme running through this—from Nisbett and Cohen, Hackett Fischer, and Wyatt-Brown to Lemann, from Canton to Chicago to Appalachia—is that concentrated poverty and violence don't exist in a vacuum. They are tied into cultural tendencies, political systems, and economic structures passed down from generation to generation. And they are tendencies that can jump their historical tracks. A 2009 study integrated Nisbett and Cohen's thesis of violence and the culture of honor into American school shootings:

That the culture of honor appears to be such a robust predictor of school violence supports the hypothesis that school violence might be partially a product of long-term or recent experiences of social marginalization, humiliation, rejection, or bullying (Leary et al., 2003; Newman et al., 2005), all of which represent honor threats with special significance to people (particularly males) living in culture-of-honor states.

It's also at the heart of what Yale sociologist Elijah Anderson sees in the code of the streets: "At the heart of the street culture is an emphasis on respect, toughness, retribution, and ultimately, violence. Anderson suggested that the street culture emphasizes maintaining the respect of others, toughness, and exacting retribution when someone disrespects you through the use of violence." This code is eerily similar to Hackett Fischer's description of Andrew Jackson, the president who was taught to go outside the rule of law and settle things hisself:

The classical example of this attitude towards violence was Andrew Jackson. A friend who knew him well for forty years said "no man knew better than Andrew Jackson when to get into a passion and when not." James Parton commented that Jackson's anger was "a Scotch-Irish anger. It was fierce, but never had any ill effect upon his purposes; on the contrary, he made it serve him, sometimes, by seeming to be much more angry than he was; a way with others of his race."

But Jackson was brilliant and self-controlled; not all his contemporaries were: "Jackson's strategy of controlled anger worked because most rage was genuine in this culture. Violence often consisted of blind, unthinking acts of savagery by men and women who were unable to control their own feelings." Alcohol abuse was frequent, and children started drinking early. "In poorer families," Wyatt-Brown writes, "a dram of whiskey was the early antebellum schoolboy's fare for breakfast. Brantley York, a North Carolinian yeoman's son, seldom left for school, he recalled, without first having a stiff glass."

Randolph Roth takes issue with the culture of honor thesis in his longitudinal study American Homicide:

He has determined that four factors correlate with the homicide rate: faith that government is stable and capable of enforcing just laws; trust in the integrity of legitimately elected officials; solidarity among social groups based on race, religion, or political affiliation; and confidence that the social hierarchy allows for respect to be earned without recourse to violence. When and where people hold these sentiments, the homicide rate is low; when and where they don’t, it’s high.

But they are not necessarily contradictory. The mistrust of legal and governmental means of recourse, that no man should "sue anybody for slander, assault, and battery," is similar to what Robert Sampson, in his study of Chicago neighborhood violence, calls "legal cynicism":

a distinction between the tolerance of deviance and cynicism about the applicability of law. One can be highly intolerant of crime, but live in a disadvantaged context bereft of legal sanctions and perceived justice. In fact, we suggest that this is exactly the sort of context found in many ghetto-poverty areas of our large cities where lower-income minorities are disproportionately concentrated. Crime there is usually high, but that does not imply, nor is there consistent evidence, that African American residents are tolerant of crime.

Crime was also not tolerated in the rural south of the 19th century; violence as a response to crime, or to pre-empt crime, was. This belief continued well into the 20th century, as the fear of vigilante justice, due to the overwhelmingly large black population, created both vigilante justice in the form of the Klan, which evolved into de facto vigilante justice from law enforcement itself, further undermining faith in just laws and a stable government: "After the Civil War, [slave patrols] seamlessly morphed into the Ku Klux Klan, the Red Shirts and other extra-legal organizations with the same purpose: to keep the black population cowed and under control. Fear of the black population is also why Southern society long accepted brutality in law enforcement to a greater degree than other parts of the country did."

Is it crazy to think that British folkways were the seed of American violence? Perhaps not. America's legal system is intimately tied to British common law, where we get habeas corpus and jury trials. U.S. v. Miller, the first significant Second Amendment decision of the 20th century, is based in Blackstone, The Wealth of Nations, and the colonial history of militias, divining the limits of gun control in the gangster era from 17th-century militia laws. It's not unthinkable that the codes outlining the use of power and violence, particularly in places where there was less recourse to the law, have also followed the same principle of stare decisis.

There are a lot of reasons I admire the culture I grew up in; from the isolation and self-reliance of the backcountry, as southern Illinois native Jeff Biggers writes in The United States of Appalachia, "a remarkable procession of Appalachian-born innovators have gone from these hills, as Thomas Wolfe wrote, to find and shape the great America of our discovery." But it's also a region marked by instability, poverty, and mortality. The twin epidemics of painkiller abuse and black lung are new symptoms of old pathologies, if not as extreme as they were in the form of America's great sins: the Civil War, and the peculiar institution that gave birth to it, as well as the derivative institution of debt peonage that scarred the land for long after the South was defeated. A new book semiseriously suggests giving the region what it wanted 150 years ago, but it's far too late for that—the house, no longer divided, has no choice but to stand.

Comments are closed.