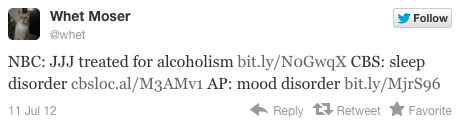

Until yesterday evening, Jesse Jackson Jr.'s leave of absence from Congress had been a mystery, attributed to exhaustion, then either more or less specifically to "certain physical and emotional ailments." Then, in the space of about half an hour, this happened:

Today the word from his staff is a mood disorder, citing an unnamed physician; NBC cites a "family friend" saying that it's "severe clinical depression [and] a problem with alcohol"; the Sun-Times notes that his camp denies that he's being treated for alcoholism, and that an aide says he has sleep disorders.

It's confusing, but so is mental illness. Symptoms and causes overlap. Depression can cause a sleep disorder; sleep disorders can exacerbate depression; alcohol can make both worse, and can serve as self-medication for both. A month into severe depression is a profoundly confusing time—not just because of the fluidity of the symptoms, but because it also hampers one's ability to process information, not unlike Alzheimers:

"The best way to think about depression is as a mild neurodegenerative disorder," says Ronald Duman, a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at Yale. "Your brain cells atrophy, just like in other diseases [such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's]. The only difference with depression is that it's reversible. The brain can recover."

Depression is doubly confusing. Everyone has bad days; some of us have bad weeks. Determining the point when it's no longer a rough patch and is something more serious is difficult, and is made even more difficult by the fact that, as things get worse, the brain is even less able—on a physical level—to make sense of it.

David Weigel charts the evolution of the story from missed votes, to "exhaustion," to mood disorder, and asks: "Has anyone ever screwed up an explanation quite this much?" Diagnosing a mental illness, in the space of less than a month, is fraught with problems; it's much less cut and dry than having tweeted a crotch picture.

Oh, and Weigel also writes: A "residential treatment facility" is a long way of describing "rehab." Actually, it's not. Mood disorders and substance abuse can easily overlap, but you can go into residential treatment in the absence of addiction.

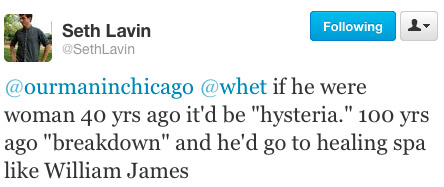

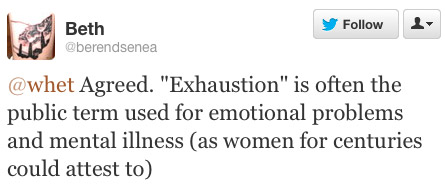

Jackson's camp has been criticized for being unclear. Mental illness is inherently unclear, from both the inside and out, but the language surrounding it is also opaque. The first report from his staff was "exhaustion"—which is actually what severe depression can feel like, but I'll grant that it's widely viewed as code for "rich person with a substance abuse problem," just as Weigel's reaction suggests that "residential treatment facility" has the same implication. But this has been uneven ground for decades:

(And if he was a male politician 40 years ago it would be "nervous exhaustion," and George McGovern would throw him from the ticket. It's worth noting, however, despite the epic fiasco that turned into, Tom Eagleton was re-elected and served in the Senate another 12 years.)

We have a bad vocabulary for discussing mental illness and its overlapping problems. (Here's an idea: reserve "exhaustion," if we must have a euphemism, for mental illness, and restore "gone to Dwight" for substance addiction.) Some of it stems naturally from the categorical fog of mood disorders, but stigma is another factor, and Jackson—as a black male public figure—could, from his perspective, be looking at a more intense stigma than others. John Head is a journalist who worked for the Detroit Free Press, for USA Today as Atlanta bureau chief, and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution as a columnist and member of the editorial board—all while suffering from ongoing severe depression into his 40s, reaching the point of going through a dry run for his suicide. In his book Black Men and Depression, Head recounts his experiences, while putting them in the context of black culture and history.

The mind-set that allows us to visualize a "Whites Only" sign on the doorway to depression and other mental illnesses wasn't then and isn't now limited to black folks in small towns. At a banquet I attended in the spring of 2003, I sat next to one of the living legends of the civil rights movement. He labored on the front lines of the fight for black equality for most of his adult life. Always known for his intellect and sophistication, he eventually became a man of wealth and a power in the political and corporate world. While we chatted, the fact that I was writing a book came up.

"What's it about?" he asked.

"It's about black men and depression," I said. "One of the main points I'm trying to make is that depression is a problem that just isn't talked about in the black community."

"You know, we didn't have any of that stuff until after integration," he said.

I didn't quite know how to respond to that. I just gave him one of those smiles that say, "You're kidding, right?"

He picked up on it immediately. "I'm serious!" he exclaimed. "Dead serious. Just think about it."

Carl Bell, the pioneering psychologist at UIC, has written extensively about depression in the black community; responding to a study that found African-Americans (and Mexican-Americans) are less likely to get treatment for depression than other American ethnic groups, he attributed it to a range of issues: "[P]artly, it's access. Partly, it's fear. Partly, for mental health, it's stigma. Partly, it's discrimination that's experienced when you go to a health care provider and they make stereotypic assumptions about who you are and how you are and what you're capable of."

Will no one "pick on him or think less of him if he's ill"? I hope not, but I can't be entirely confident, either.

One month is an eternity in the news cycle; in the cycle of serious mood disorders, it's only the beginning. The clarity that Jackson and his camp owe constituents is complicated by the distinct lack of clarity surrounding what he's reportedly suffering from—and may well be reflected by the range of what's been reported in the past day. There's a lot of fog to cut through, not least for Jackson himself.

Photograph: Chicago Magazine