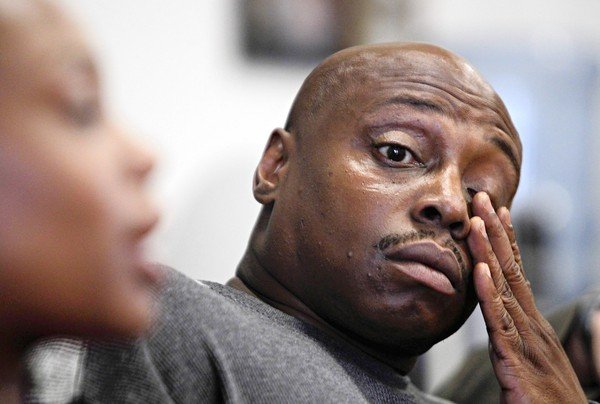

Michael Tillman

Another Burge settlement was just reached:

A panel of aldermen recommended Monday that the city pay $5.375 million to Michael Tillman, who spent more than two decades in prison for the 1986 rape and murder of a South Side woman whose body was found in a vacant apartment in a building where he lived and worked as a maintenance man.

Tillman said he confessed to the crime only because detectives under Burge's command punched him, beat him with a phone book, threatened to kill him and held a plastic bag over his head, among other torture. He recanted the confession within days.

The Tillman settlement is an even bigger deal than most of the Burge settlements for a couple reasons. First, former Mayor Daley had agreed to be deposed in the event that the lawsuit, which included Daley, went to trial. It's not the first time he's been scheduled to be deposed, and not the first time he's avoided it. (Not that it's unusual for the city to settle CPD-related lawsuits; indeed, we spend a disproportional amount of money on it.*) Daley was the state's attorney at the time, and John Conroy laid out 20 questions he'd ask the then-Mayor, if he could get him on the stand:

In 1987, two years before you left the state's attorney's office, the Illinois Supreme Court overturned Andrew Wilson's conviction, making specific mention of the injuries noted by the staff at Mercy Hospital. It's highly unusual for the state Supreme Court to overturn the conviction of a cop killer. Yet even then you didn't order an inquiry into the torture accusations. Why not?

Tillman's case is also significant because, after three decades, no prosecutor had ever acknowledged that coercion had occurred in any of the Burge cases. Tillman's was the first. Even Tillman's case might have slipped through the cracks had it not been taken up by then-freelance writer Jessica Pupovac (now at NPR StateImpact), who wrote a lengthy piece on Tillman for AlterNet:

Michael Tillman's lawyer presented physical evidence of abuse in court, including the blue jeans that Tillman wore during his interrogation, which hadn't been washed since and were still stained with blood. He also showed scars on his wrists from where the handcuffs pulled while he was being beaten. Despite this, and despite the fact that there was no physical evidence linking him to the crime scene, the jury did not believe him.

(Two men were found driving the victim's stolen car, who tipped police off to another man, Clarence Trotter, who was in possession of the victim's camera and stereo, and left fingerprints at the scene. After going to prison, DNA tests matched Trotter to the 1981 rape and murder of a Lincoln Park woman.)

There's another odd story related to Jon Burge that's arisen, detailed by Jamie Kalven. Jailhouse lawyer Kilroy Watkins was picked up for armed robbery and confessed to a murder to two CPD detectives, both of whom come up in a long Tribune investigation by Maurice Possley, Steve Mills and Ken Armstrong, "Veteran detective's murder cases unravel":

Williams was arrested the next day. He told the Tribune that he was handcuffed to a radiator pipe for hours and urinated on himself when no one allowed him to use a washroom.

[snip]

The confession he gave to Boudreau and Halloran was even more detailed than either Hill's or Young's–containing comments allegedly made by Morgan during the assault.

[snip]

But sometime after he gave his statement, Williams figured out that he had been in Cook County Jail on a narcotics charge at the time of the crime. Detectives confirmed Williams' alibi and he was released, but prosecutors still tried Young and Hill.

So Watkins wants the police misconduct files for Boudreau and Halloran released. So he filed a FOIA. It was granted, on the basis that such records aren't private. Then it wasn't, because "the court did not have jurisdiction because he had filed his appeal too early." It's confusing; Kalven writes that it "would be generous to describe this decision as hyper-technical." The state Supreme Court kicked it back to the Court of Appeals for a ruling on the merits, which bears watching.

* As Angela Caputo detailed in a Chicago Reporter investigation, lawsuit settlements in police misconduct cases are extremely common:

[C]onducting investigations into the lawsuits isn’t without complications, Rosenzweig said. Many never make it past the initial review stage because, under state statute and the police union contract, the officers are off-limits unless a plaintiff signs a sworn affidavit. In a system where out-of-court settlements dominate, cases can be closed before plaintiffs are even deposed, she said. And even when depositions are completed, they can be thin on essential details.

Photograph: Chicago Tribune