Thanks in large part to WBEZ, there's been a lot of discussion about segregation in Chicago. Then again, given how segregated the city is, there's often discussion of segregation—if not from politicians, necessarily, at least in the media and academia. It's the result of a lot of factors, but one thing history makes clear is the significance of housing policy and housing prices in the creation of segregated neighborhoods in the city. Racial bias—discriminatory block clubs, bombings and riots tantamount to terrorism—skewed the market during the Great Migration, driving up prices for the African-Americans flooding the city. It's odd to think of the Rosenwald Apartments, built by Julius Rosenwald as nice, reasonably-priced housing for middle-class blacks, as a philanthropic project in "affordable" housing when it really amounted to typical middle-class apartments at market-rate prices, but such was the nature of the market at the time.

The open discrimination of the block clubs and encoded FHA lending practices has fallen away, but there's still a race premium on housing in Chicago, according to a new NBER paper co-authored by Marcus Casey of UIC. The authors looked at four cities—Chicago, Baltimore, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The latter two are less segregated; Chicago and Baltimore are more segregated, and also share in common lawsuits against Wells Fargo, thanks in part to work done by the Chicago Reporter:

"Minorities who come in to get a loan tend to be steered to higher-cost loans though they may qualify for a better loan," said Gail Parson, lead housing staff for the National Training and Information Center, often referred to as NTIC, which does research and community organizing in Chicago. Federal mortgage lending data has been public nationwide since the group helped pass the nation's first Home Mortgage Disclosure Act in the mid-'70s.

So the results of the NBER analysis shouldn't be surprising: "The estimated premiums for black buyers are highest in the Chicago and Maryland areas, where they represent a reasonably large fraction of the population and segregation levels have historically been very high. There is weaker evidence for price discrimination for black buyers in Los Angeles and San Francisco, where the estimated premiums are 1.1-1.2 percent."

In the Chicago area, blacks represent only eight percent of homebuyers, and "a considerable fraction of white-to-black sales but far fewer black-to-white transactions." The highest premium paid by any race in any of the cities studied was in Cook County: 4.7 percent, controlled for wealth, income, neighborhood composition, and credit access. 4.7 percent is a lot of money on a house in the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars: an additional $7,050 on a $150,000 house, not including interest, the equivalent of about eight months worth of groceries for a family of four.

Is it abject discrimination? Not between buyers and sellers, the authors argue: "the average price premium paid by black and Hispanic buyers is about the same regardless of the race of the seller" (emphasis theirs).

The authors were unable to isolate a specific cause for this, but they did have one interesting finding that suggests one possible cause:

This analysis also revealed that sellers of each race do roughly as well on average when they sell their homes, no matter the race of the buyer. Thus, any disadvantage that black and Hispanic buyers face when purchasing homes disappears when it comes time to sell. While certainly not conclusive, this pattern suggests that the relative inexperience of black and Hispanic buyers, due to the historically lower rates of home ownership among the black and Hispanic households, may contribute to the higher prices that they initially pay upon entering the market.

That tracks with what Kimbriell Kelly found in researching her piece on lending disparities in Chicago:

Jernigan said that participants feel more empowered as they progress through the classes. Some show up with questions about investment properties. Experts say it's that confidence that has catapulted whites to more approvals while the lack of it has prevented African Americans from demanding more competitive rates.

"If you know you can get approved for a loan, you don't worry about getting approved. You say, 'I'm not taking your 6 percent rate. I want 5.25 percent,'" said Gardner of MidAmerica Bank. "There are still a lot of blacks who have fear of rejection [and] do not feel comfortable in financial transactions. They are more concerned about getting to 'yes' than the best, correct loan."

While there's less systemic discrimination in housing in Chicago and elsewhere than there was in the mid-20th century, history still weighs on the market—and not just on buyers, the authors suggest: "Another potential explanation is that black and Hispanic buyers face higher search costs in the housing market…. Knowing that black and Hispanic buyers typically face higher costs of continuing to search, sellers might statistically discriminate by holding out for a higher price (i.e., use a higher reservation price) in negotiations."

It's not just a problem for those who lose their houses, or hang onto them while paying substantially more. As Megan Cotrell has written, mortgages blowing up en masse drove the financial crisis, and racial disparities in lending and homeownership played a vital role. The plague of abandoned homes undermines communities, lowers the value of nearby homes and the wealth of their owners, creates public-safety problems, and bleeds public coffers—instead of generating revenue for the city, the city has to pay to tear them down. The new, opaque housing disparities are a legacy of the old, encoded ones, and in some ways more difficult to address because they're ingrained in people instead of law.

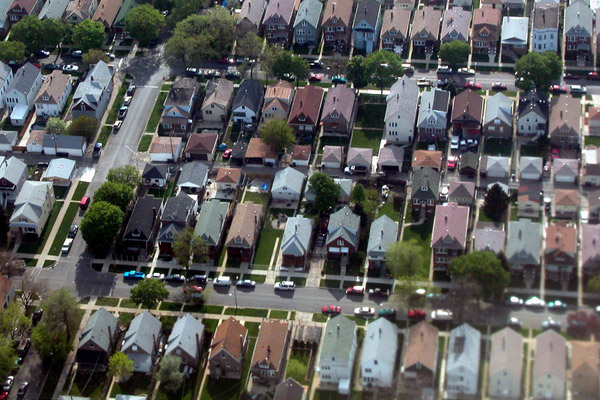

Photograph: davidwilson1949 (CC by 2.0)