Photo: David Klobucar/Chicago Tribune

As someone who voluntarily sought to live in Chicago, I'm pretty tolerant of what seems to bother less willing transplants—the winters, those are brisk; the Cubs, that's a fan base that can appreciate traditions other than success. The biggest exception is the 66 bus, which is my backup bus. When the 65, which is Club Med by comparison, isn't convenient, I prepare to push through the special snowflakes who won't move past the steps, take up my two-thirds of a seat next to some splay-legged gentleman who wants to suggest to the world that what is between his legs requires that much space, and watch the world go by.

Which always seems to include another 66 bus.

Lest this sound like sour grapes, Shaun Jacobsen at Transitized pulled the numbers for bus bunching for January–October 2012, and calculated bunching—the transit phenomena in which you wait forever for a bus to come, then finally watch as two or three arrive at the stop at the same time—as follows: "percent of timepoint headways less than one minute for buses running the same route/direction, Jan-Oct 2012." Survey says: the 66 wins by a nose over the 49 bus, with a 6.56 percent bunch rate, about twice the systemwide goal.

Jacobsen also kindly published all his data; the worst month for bunching on the CTA over that period was the 66 during October of last year, when 8.8 percent of buses were bunched, tied with the Belmont bus during the same month. It's a regular offender: fourth worst in 2010, seventh worst in 2011. Other regular offenders: the Western bus (second worst in 2011), the Clark bus (natch), and the King Drive bus, which runs all the way from Northwestern Hospital in Streeterville down to 95th and King Drive.

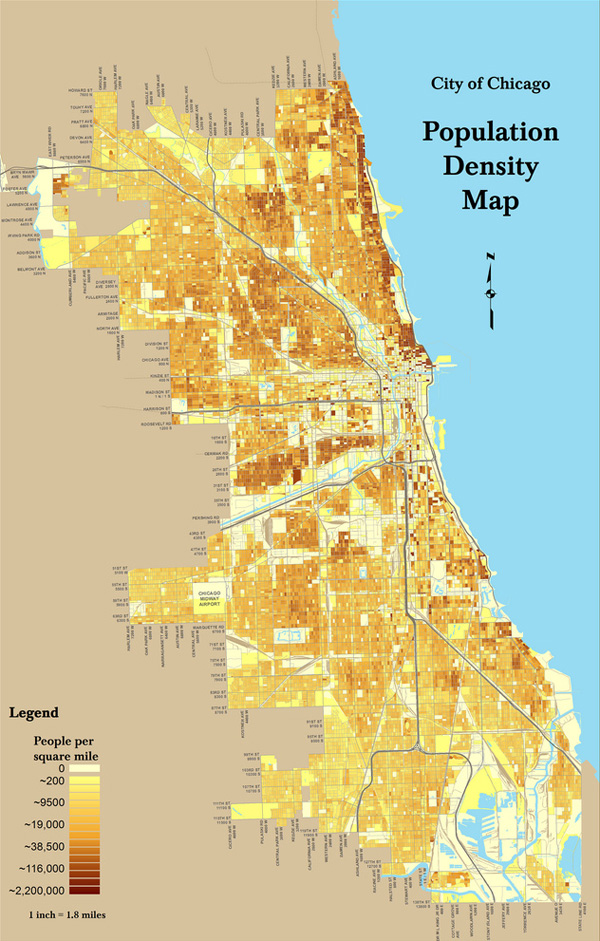

Most of the problem buses are north-side and east-side buses, reflecting the differences in population density within the city.

Map: mindfrieze/CC by 2.0

As you might expect, the buses that bunch the least are northwest- and southwest-side buses, like the 165, which runs from Midway to Archer and 63rd, and the 81W, which serves the Catherine Chevalier Woods and the Jefferson Park Blue Line terminal.

Obviously buses are going to have more problems in dense areas, but that still doesn't answer why, specifically, they bunch. The solutions involve a lot of difficult math, but the causes are more intuitive than you might expect:

Public transport vehicles – underground trains, for example – set off from the start of their routes equally spaced. The problem starts when one is briefly delayed, making more time for passengers to accumulate at stations further down the track. Since passenger boarding is the main factor delaying trains, these extra people slow the train even more.

Meanwhile, the gap between the delayed train and the one behind is shortened. That means fewer passengers for the train behind to pick up, making it pass through stations faster until it catches the train ahead. Eventually, all the trains on a route can end up crawling after the slowest, lead train.

The systematic fixes are complex, but you, too, can prevent bus bunching (a very tiny bit): by boarding fast, and chilling out when you can't board: "It’s hard to get people to understand that while you may have your trip delayed by ten minutes, the result is that we’re keeping things moving for better throughput for everyone. Or, turning it around: waiting for you would mean, ultimately, making hundreds of other people late."